Diarrhoea

Diarrhoea is a common clinical problem and there is no uniformly accepted definition of diarrhoea. Organic causes (stool weights >250 g/day) have to be distinguished from functional causes. Sudden onset of bowel frequency associated with crampy abdominal pains, and a fever will point to an infective cause; bowel frequency with loose blood-stained stools to an inflammatory basis; and the passage of pale offensive stools that float, often accompanied by loss of appetite and weight loss, to steatorrhoea. Nocturnal bowel frequency and urgency usually point to an organic cause. Passage of frequent small-volume stools (often formed) points to a functional cause (see Functional gastrointestinal disorders, below).

Mechanisms

Osmotic diarrhoea

The gut mucosa acts as a semipermeable membrane and fluid enters the bowel if there are large quantities of non-absorbed hypertonic substances in the lumen. This occurs because:

The patient has ingested a non-absorbable substance (e.g. a purgative such as magnesium sulphate or magnesium-containing antacid)

The patient has ingested a non-absorbable substance (e.g. a purgative such as magnesium sulphate or magnesium-containing antacid)

The patient has generalized malabsorption so that high concentrations of solute (e.g. glucose) remain in the lumen

The patient has generalized malabsorption so that high concentrations of solute (e.g. glucose) remain in the lumen

The patient has a specific absorptive defect (e.g. disaccharidase deficiency or glucose-galactose malabsorption).

The patient has a specific absorptive defect (e.g. disaccharidase deficiency or glucose-galactose malabsorption).

The volume of diarrhoea produced by these mechanisms is reduced by the absorption of fluid by the ileum and colon. The diarrhoea stops when the patient stops eating or the malabsorptive substance is discontinued.

Secretory diarrhoea

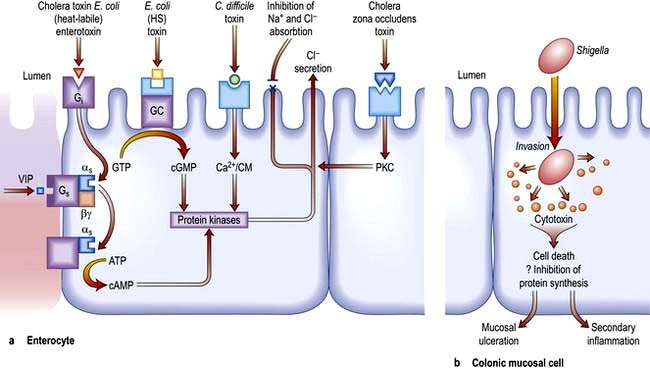

In this disorder, there is both active intestinal secretion of fluid and electrolytes as well as decreased absorption. The mechanism of intestinal secretion is shown in Figure 6.45a.

Figure 6.45 Mechanisms of diarrhoea. (a) Small intestinal secretion of water and electrolytes. Cholera toxin binds to its receptor (monosialoganglioside Gi) via fimbria (toxin co-regulated pilus) on its β-subunit. This activates the as subunit (of the Gs protein), which in turn dissociates and activates cyclic AMP (cAMP). The increase in cAMP activates intermediates (e.g. protein kinase and Ca2+) which then act on the apical membrane causing Cl− secretion (with water) and inhibition of Na+ and Cl− absorption. Heat-labile E. coli enterotoxin shares a receptor with cholera toxin. Heat-stable (HS) E. coli toxin binds to its own receptor and activates guanylate cyclase (cGMP), producing the same effect on secretion. C. difficile activates the protein kinases via Ca2+/calmodulin (Ca2+/CM). Zona occludens toxin is the product of the ZOT gene, which is the gene required for the CTX gene which encodes for cholera toxin. It has enterotoxic activity, producing secretion. Cholera and E. coli cause these effects without invasion of the cell. G, G protein consisting of subunits α, β, γ; i, inhibitory; s, stimulatory; ATP, adenosine triphosphate; GTP, guanosine triphosphate; GMP, guanosine monophosphate; GC, guanyl cyclase; PKC, protein kinase C; VIP, vasoactive intestinal polypeptide. (b) Colonic mucosal cell. This demonstrates one of the mechanisms by which an invasive pathogen (e.g. Shigella) acts. Following penetration, the pathogens generate cytotoxins which lead to mucosal ulceration and cell death.

Common causes of secretory diarrhoea are:

Enterotoxins (e.g. cholera, E. coli thermolabile or thermostable toxin, C. difficile)

Enterotoxins (e.g. cholera, E. coli thermolabile or thermostable toxin, C. difficile)

Hormones (e.g. vasoactive intestinal peptide in the Verner–Morrison syndrome, p. 370)

Hormones (e.g. vasoactive intestinal peptide in the Verner–Morrison syndrome, p. 370)

Bile salts (in the colon) following ileal resection

Bile salts (in the colon) following ileal resection

Inflammatory diarrhoea (mucosal destruction)

Diarrhoea occurs because of damage to the intestinal mucosal cell so that there is a loss of fluid and blood (Fig. 6.45b). In addition, there is defective absorption of fluid and electrolytes. Common causes are infective conditions (e.g. dysentery due to Shigella) and inflammatory conditions (e.g. ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease).

Abnormal motility

Diabetic, post-vagotomy and hyperthyroid diarrhoea are all due to abnormal motility of the upper gut. Symptoms may be exacerbated by small bowel bacterial overgrowth.

Causes of diarrhoea are shown in Table 6.21. It should be noted that the irritable bowel syndrome, colorectal cancer, diverticular disease and faecal impaction with overflow in the elderly do not cause ‘true’ organic diarrhoea (i.e. >250 g/day), even though the patients may complain of diarrhoea. Worldwide, infection and infestation are a major problem and these are discussed under the causative organisms in Chapter 4.

Table 6.21 Causes of diarrhoea

Acute diarrhoea (excluding cholera – see p. 103)

Diarrhoea of sudden onset is very common, often short-lived and requires no investigation or treatment. Although dietary causes should be considered, diarrhoea due to viral agents may also last 24–48 hours (see p. 103). The causes of other infective diarrhoeas are shown on page 119. Travellers’ diarrhoea, which affects people travelling outside their own countries, particularly to developing countries, usually lasts 2–5 days; it is discussed on page 122. Clinical features associated with the acute diarrhoeas include fever, abdominal pain and vomiting. If the diarrhoea is particularly severe, dehydration can be a problem; the very young and very old are at special risk from this. Investigations are necessary if the diarrhoea has lasted more than 1 week. Stools (up to three) should be sent immediately to the laboratory for culture and examination for ova, cysts and parasites and Clostridium difficile toxin assay. If the diagnosis has still not been made, a sigmoidoscopy and rectal biopsy should be performed and imaging should be considered. Viral and bacterial infective diarrhoeas do not last more than two weeks.

Oral fluid and electrolyte replacement is often necessary. Special oral rehydration solutions (e.g. sodium chloride and glucose powder) are available for use in severe episodes of diarrhoea, particularly in infants. Antidiarrhoeal drugs are thought to impair the clearance of any pathogen from the bowel but may be necessary for short-term relief (e.g. codeine phosphate 30 mg four times daily or loperamide 2 mg three times daily). Antibiotics are occasionally necessary (see p. 125) depending on the organism.

Chronic diarrhoea

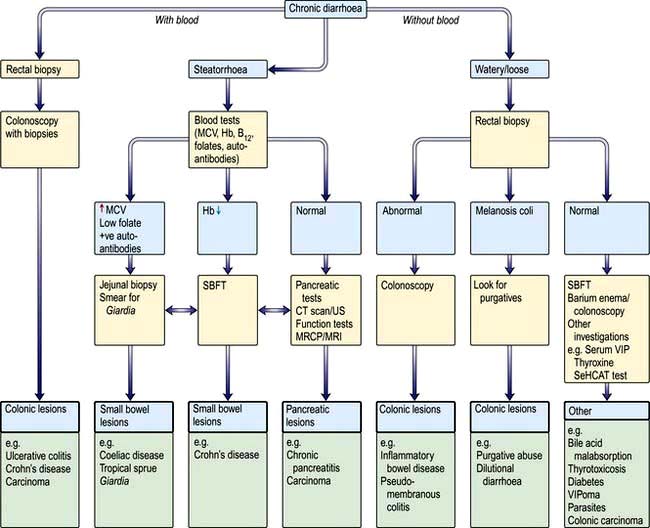

This always needs investigation. The flow diagram in Figure 6.46 is illustrative; whether the large or the small bowel is investigated first will depend on the clinical story of, for example, bloody diarrhoea or steatorrhoea. The investigations and treatment are described in detail under the individual diseases. Colonoscopy is usually necessary if stool cultures are negative and small bowel disease is not suspected.

Figure 6.46 Flow diagram for the investigation of chronic diarrhoea. Note: All patients should have had stool cultures with toxin testing for C. difficile. SBFT, small bowel follow-through; VIP, vasoactive intestinal polypeptide; MRCP, magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography; SeHCAT, 75Se-homocholic acid taurine.

C. difficile-associated diarrhoea (pseudomembranous colitis)

Pseudomembranous colitis (see p. 122) may develop following the use of any antibiotic. Diarrhoea occurs in the first few days after taking the antibiotic or even up to 6 weeks after stopping the drug. The causative agent is Clostridium difficile (see p. 122).

Bile acid malabsorption

Bile acid malabsorption is an underdiagnosed cause of chronic diarrhoea and many patients with this disorder are assumed to have irritable bowel syndrome. Bile acid diarrhoea occurs when the terminal ileum fails to reabsorb bile acids. Bile acids (particularly the dihydroxy bile acids: deoxycholate and chenodeoxycholate) when present in increased concentrations in the colon lead to diarrhoea by reducing absorption of water and electrolytes and, at higher concentrations, inducing secretion as well as increasing colonic motility. A variety of causes of bile acid malabsorption are recognized (Table 6.22).

Table 6.22 Causes of bile acid diarrhoea

Bile acid malabsorption should be considered not only in patients with chronic diarrhoea of unknown cause but also in patients with diarrhoea and associated disease who are not responding to standard therapy (e.g. patients with terminal ileal Crohn’s disease, microscopic inflammatory colitis).

Diagnosis is made using the SeHCAT test in which a radiolabelled bile acid analogue is administered and percentage retention at 7 days calculated (<19% retention abnormal). Treatment is with bile salt sequestrants such as cholestyramine, a resin which binds and inactivates the action of bile acids in the colon. The best results of treatment are obtained in patients with a SeHCAT retention of <5%.

Factitious diarrhoea

Factitious diarrhoea accounts for up to 4% of new patients with diarrhoea attending gastroenterology clinics.

Purgative abuse

This is most commonly seen in females who surreptitiously take high-dose purgatives and are often extensively investigated for chronic diarrhoea. The diarrhoea is usually of high volume (>1 L daily) and patients may have a low serum potassium. Biochemical analysis of the stool may help diagnose laxative abuse. Management is difficult as most patients deny purgative ingestion. Purgative abuse often occurs in association with eating disorders and patients may need psychiatric help.

Diarrhoea in patients with HIV infection

Chronic diarrhoea is a common symptom in HIV infection, but HIV’s role in the pathogenesis of diarrhoea is unclear. Cryptosporidium (see p. 110) is the pathogen most commonly isolated. Isospora belli and microsporidia have also been found.

The cause of the diarrhoea is often not found and treatment is symptomatic. Table 6.23 shows the conditions affecting the gastrointestinal tract in patients with AIDS.

Table 6.23 Gastrointestinal problems in patients with AIDS

| Symptoms | Causes |

|---|---|

Mouth/oesophagus |

|

Dysphagia |

Herpes simplex virus (HSV) |

Retrosternal discomfort Oral ulceration |

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) |

Candidiasis |

|

Small bowel/colon |

|

Chronic diarrhoea |

Parasites: |

Steatorrhoea |

Entamoeba histolytica |

Weight loss |

Giardia intestinalis |

|

Cryptosporidium |

|

Blastocysts hominis |

|

Isospora belli |

|

Microsporidia |

|

Cyclospora cayetanensis |

|

Viruses: |

|

CMV/HSV, adenovirus |

|

Bacteria: |

|

Salmonella |

|

Campylobacter |

|

Shigella |

|

Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare |

|

Non-infective |

|

enteropathy – cause unknown |

Rectum/colon |

|

Bloody diarrhoea |

Bacterial infection (e.g. Shigella) |

Any site |

|

Weight loss |

Neoplasia: |

Diarrhoea |

Kaposi’s sarcoma |

|

Lymphoma |

|

Squamous carcinoma |

|

Infection – disseminated, e.g. |

|

Mycobacterium |

|

avium-intracellulare |

|

HAART therapy |