Gall bladder and biliary system

The structure, formation and function of bile is discussed on page 305.

Gallstones

Prevalence of gallstones

Gallstones may be present at any age but are unusual before the 3rd decade. The prevalence of gallstones is strongly influenced both by age and gender. There is a progressive increase in the presence of gallstones with age but the prevalence is two to three times higher in women than in men, although this difference is less marked in the 6th and 7th decade. At this age, the prevalence ranges between 25% and 30%. The increase in life expectancy is reflected in an increased burden of symptomatic gallstone disease. There are considerable racial differences, gallstones being more common in Scandinavia, South America and Native North Americans but less common in Asian and African groups.

Types of gallstones

The large majority of gallstones are of two types: cholesterol (containing >50% of the sterol) and less frequently ‘pigment stones’, being predominantly composed of calcium bilirubinate or polymer-like complexes with calcium, copper and some cholesterol.

Cholesterol gallstones

This type of stone accounts for 80% of gallstones in the western world. The formation of cholesterol stones is the consequence of cholesterol crystallization from gall bladder bile. This is dependent upon three factors:

The majority of cholesterol is derived from hepatic uptake from dietary sources. However, hepatic biosynthesis may account for up to 20%. The rate-limiting step in cholesterol synthesis is β-hydroxy-β methyl glutaryl CoA (HMG-CoA) reductase, which catalyses the first step, i.e. the conversion of acetate to mevalonate. The cholesterol formed is co-secreted with phospholipids into the biliary canaliculus as unilamellar vesicles. Cholesterol will only crystallize into stones when the bile is supersaturated with cholesterol relative to the bile salt and phospholipid content. This can occur as a consequence of excess cholesterol secretion into bile which, in some instances, has been shown to be due to an increase in HMG-CoA reductase activity. Recently, leptin (see p. 216) has been shown to increase cholesterol secretion into bile. Elevated levels of leptin during rapid weight loss may account for the increased incidence of cholesterol gallstones. An alternative mechanism of supersaturation is a decreased bile salt content which may occur as a consequence of bile salt loss (e.g. terminal ileal resection or ileal involvement with Crohn’s disease).

The composition of the bile salt pool may also influence the ability to maintain cholesterol in solution. There is evidence that an increased proportion of the secondary hydrophobic bile acid (deoxycholic acid) in the bile acid pool may predispose to cholesterol stone formation. This has been linked with slow colonic transit during which the primary bile acid cholic acid may undergo microbial enzyme metabolism yielding deoxycholic acid which is then absorbed back into the bile salt pool (see Fig. 7.4).

While cholesterol supersaturation of bile is essential for cholesterol stone formation, many individuals in whom such supersaturation occurs will never develop stones. It is the balance between cholesterol crystallizing and solubilizing factors that determines whether cholesterol will crystallize out of solution. A number of lipoproteins have been reported as putative crystallizing factors.

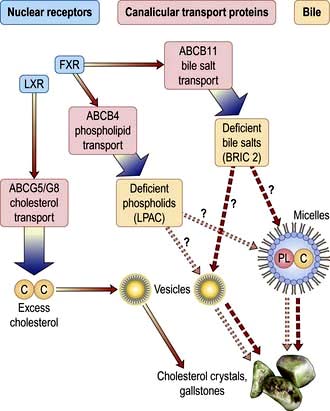

There is increasing evidence from epidemiological, family and twin studies of the role of genetic factors in gallstone formation. A number of lithogenic genes have been identified which may interact with environmental factors. The process of bile formation is maintained by a network of ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters in the hepatocyte canalicular membrane which enable biliary secretion of cholesterol, bile salts and phospholipids. This process is regulated by the nuclear receptors FXR and LXR. Loss of function mutations in specific ABC transporter genes have been associated with cholesterol gallstones secondary to bile salt and phospholipid deficiencies within the nascent bile (Fig. 7.29). However, monogenic susceptibility appears uncommon. There are rare cases in which a single missense mutation of the MDR3 gene has been associated with extensive intra- and extrahepatic cholelithiasis at an early (<40 years) age.

Figure 7.29 Nascent bile formation at the hepatocytic canalicular membrane, biliary cholesterol solubilization and gallstone formation. ABCG5-G8 transports cholesterol into bile (regulated by nuclear receptor LXR). ABCB11, ABCB4 transport bile salts and phosphatidylcholine into bile (regulated by nuclear receptor FXR). Bile cholesterol is solubilized in mixed micelles or contained in cholesterol–phospholipid vesicles. Most gallstones are due to excess biliary cholesterol secretion and subsequent crystallization from supersaturated vesicles (continuous lines). LPAC (low phospholipid associated cholelithiasis) occurs if there is phospholipid in bile due to function mutations in gene ABCB4. Benign recurrent intrahepatic cholestasis (BRIC) type 2 is characterized by bile salts in bile due to function mutations in gene ABCB11. In both LPAC and BRIC type 2, there is increased risk of gallstone formation.

A high cholesterol diet increases biliary cholesterol secretion and decreases bile salt synthesis and bile salt pool in cholesterol gallstone subjects but not in controls. These findings suggest that increased intestinal uptake of the sterol could play a role in gallstone pathogenesis. In support of this observation, pharmacological inhibition of cholesterol absorbtion prevents gallstone formation in a mouse model. This may offer a potential therapy for the management/prevention of gallstone formation in patients.

Gall bladder motility represents a further factor that may influence the cholesterol crystallization from supersaturated bile. There is evidence from animal models that gall bladder stasis leads to cholesterol crystallization mediated by hypersecretion of mucin.

Abnormalities of gall bladder motility have been suggested as factors in such circumstances as pregnancy, multiparity and diabetes as well as octreotide-related gall bladder stones (p. 954). Recognized risk factors for gallstones are shown in Table 7.17.

Table 7.17 Risk factors for cholesterol gallstones

Bile pigment stones

The pathogenesis of pigment stones is entirely independent of cholesterol gallstones. There are two main types of pigment gallstones, black and brown.

Black pigment gallstones are composed of calcium bilirubinate and a network of mucin glycoproteins that interlace with salts such as calcium carbonate and/or calcium phosphate. These stones range in colour from deep black to very dark brown and have a glass-like cross-sectional surface on fracturing. Black pigment stones are seen in 40–60% of patients with haemolytic conditions such as sickle cell disease and hereditary spherocytosis in which there is chronic excess bilirubin production. However, the majority of pigment stones occur without haemolysis. There has been evidence that bile salt loss into the colon (consequent upon ileal resection or ileal disease) promotes solubilization and colonic reabsorption of bilirubin. This enhances the enterohepatic circulation and biliary secretion of bilirubin with the formation of gallstones. Pigment stones have also been linked with bacterial colonization of the biliary tree. Some pigment stones have been shown to contain bacteria, many of which produce glucuronidase and phospholipase, factors that are known to facilitate stone formation. It is speculated that this subclinical bacterial colonization of the bile duct is responsible for the pigment stone formation.

Brown stones are usually of a muddy hue and on cross-section seem to have alternating brown and tan layers. These stones are composed of calcium salts of fatty acids as well as calcium bilirubinate. They are almost always found in the presence of bile stasis and/or biliary infection. Brown stones are a common cause of recurrent bile duct stones following cholecystectomy and may also be found in the intrahepatic ducts in circumstances of duct disease such as Caroli’s syndrome and primary sclerosing cholangitis. In the Far East such brown stones are identified within both the intra- and extrahepatic biliary tree and have been linked with chronic parasitic infection.

Clinical presentation of gallstones

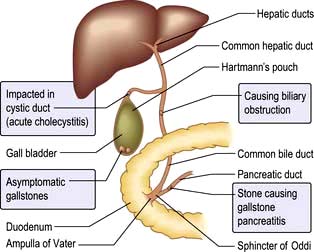

The majority of gallstones are asymptomatic and remain so during a person’s lifetime. Gallstones (Fig. 7.30) are increasingly detected as an incidental finding at the time of either abdominal radiography or ultrasound scanning. Over a 10–15-year period, approximately 20% of these stones will be the cause of symptoms with 10% having severe complications. Once gallstones have become symptomatic there is a strong trend towards recurrent complications, often of increasing severity. Gallstones do not cause dyspepsia, fat intolerance, flatulence or other vague upper abdominal symptoms.

Biliary or gallstone colic

Biliary colic is the term used for the pain associated with the temporary obstruction of the cystic or common bile duct by a stone usually migrating from the gall bladder. Despite the term ‘colic’, the pain of stone-induced ductular obstruction is severe but constant and has a crescendo characteristic. Many sufferers can relate the symptoms to over-indulgence with food, particularly when this has a high fat content. The most common time of day for such an episode is in the mid-evening and lasting until the early hours of the morning.

The initial site of pain is usually in the epigastrium but there may be a right upper quadrant component. Radiation may occur over the right shoulder and right subscapular region.

Nausea and vomiting frequently accompany the more severe attacks. The cessation of the attack may be spontaneous after a number of hours or terminated by the administration of opiate analgesia. More protracted pain, particularly when associated with fevers and rigors, suggests secondary complications such as cholecystitis, cholangitis or gallstone-related pancreatitis (see below).

Acute cholecystitis

The initial event in acute cholecystitis is obstruction to gall bladder emptying. In 95% of cases, a gall bladder stone can be identified as the cause. Such obstruction results in an increase of gall bladder glandular secretion leading to progressive distension which in turn may compromise the vascular supply to the gall bladder.

There is also an inflammatory response secondary to retained bile within the gall bladder. Infection is a secondary phenomenon following the vascular and inflammatory events described above.

The initial clinical features of an episode of cholecystitis are similar to those of biliary colic described above. However, over a number of hours, there is progression with severe localized right upper quadrant abdominal pain corresponding to parietal peritoneal involvement in the inflammatory process. The pain is associated with tenderness and muscle guarding or rigidity. Occasionally the gall bladder can become distended by pus (an empyema) and rarely an acute gangrenous cholecystitis develops which can perforate, with generalized peritonitis.

Investigations

Biliary colic as a consequence of a stone in the neck of the gall bladder or cystic duct is unlikely to be associated with significant abnormality of laboratory tests. Acute cholecystitis is usually associated with a moderate leucocytosis and raised inflammatory markers (e.g. C-reactive protein).

The serum bilirubin, alkaline phosphatase and aminotransferase levels may be marginally elevated in the presence of cholecystitis alone, even in the absence of bile duct obstruction. More significant elevation of the bilirubin and alkaline phosphatase is in keeping with bile duct obstruction.

The serum bilirubin, alkaline phosphatase and aminotransferase levels may be marginally elevated in the presence of cholecystitis alone, even in the absence of bile duct obstruction. More significant elevation of the bilirubin and alkaline phosphatase is in keeping with bile duct obstruction.

An abdominal ultrasound scan is the single most useful investigation for the diagnosis of gallstone-related disease (Fig. 7.31). It has a positive predictive value of 92% and a negative predictive value of 95% in patients with a clinical history of acute cholecystitis and Murphy’s sign. Look for:

An abdominal ultrasound scan is the single most useful investigation for the diagnosis of gallstone-related disease (Fig. 7.31). It has a positive predictive value of 92% and a negative predictive value of 95% in patients with a clinical history of acute cholecystitis and Murphy’s sign. Look for:

Figure 7.31 Ultrasound scan in a patient with acute cholecystitis. There is a stone (casting an acoustic shadow – thin arrow) impacted in the gall bladder neck, with a distended gall bladder (thick arrow) and thickening and oedema of the gall bladder wall.

Gallstones are a common finding in an ageing population, and in the absence of specific symptoms great care should be taken when determining whether the gallstones are responsible for the symptoms.

Biliary scintigraphy using technetium derivatives of iminodiacetate. These isotopes are taken up by hepatocytes and excreted into bile. They delineate the extrahepatic biliary tree. The absence of cystic duct and gall bladder filling provides evidence towards acute cholecystitis although the findings must be closely correlated with the presenting symptoms.

Biliary scintigraphy using technetium derivatives of iminodiacetate. These isotopes are taken up by hepatocytes and excreted into bile. They delineate the extrahepatic biliary tree. The absence of cystic duct and gall bladder filling provides evidence towards acute cholecystitis although the findings must be closely correlated with the presenting symptoms.

Differential diagnosis

Typical cases of biliary colic are usually suspected by the clinical history. The differential diagnosis includes the irritable bowel syndrome (spasm of the hepatic flexure), carcinoma of the right side of the colon, atypical peptic ulcer disease, renal colic and pancreatitis.

The differential diagnosis of acute cholecystitis includes a number of other conditions marked by severe right upper quadrant pain and fever, e.g. acute episodes of pancreatitis, perforated peptic ulceration or an intrahepatic abscess. Conditions above the right diaphragm such as basal pneumonia as well as myocardial infarction may on occasions mimic the clinical picture.

Management of gall bladder stones

Cholecystectomy

Cholecystectomy is the treatment of choice for virtually all patients with symptomatic gall bladder stones. In patients admitted with specific gallstone-related complications (see below), cholecystectomy should be carried out during the period of that admission to prevent the risk of recurrence. For those presenting with pain alone an elective procedure can be planned but the waiting time should be minimized to avoid the high risk of recurrent symptoms (approximately 30% over 4 months) and the need for another hospital admission.

Cholecystectomy should not be performed in the absence of typical symptoms just because stones are found on investigation. There is an ongoing debate as to whether prophylactic cholecystectomy is justified in young patients found to have small stones. Such patients have a long period over which they may develop symptomatic disease and small stones are an independent risk factor for the potentially serious complication of gallstone pancreatitis. Each case should be discussed on an individual risk benefit basis.

The laparotomy approach to cholecystectomy has now been replaced by the laparoscopic technique. Postoperative pain is minimized with only a short period of ileus and the early ability to mobilize the patient. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy can be safely carried out on a day-care basis in otherwise fit patients (although in most cases an overnight stay remains the norm). This has considerable cost benefits over open cholecystectomy, which is now reserved for a small proportion of patients with contraindications such as extensive previous upper abdominal surgery, ongoing bile duct obstruction or portal hypertension.

In approximately 5% of cases a laparoscopic cholecystectomy is converted to an open operation because of technical difficulties, in particular adhesions in the right upper quadrant or difficulty in identifying the biliary anatomy.

Acute cholecystitis

The initial management is conservative, consisting of nil by mouth, intravenous fluids, opiate analgesia and intravenous antibiotics (dictated by local policy with options including extended-spectrum cephalosporins, fluoroquinolones or piperacillin/tazobactam).

Cholecystectomy is usually delayed for a few days to allow the symptoms to settle but can then be carried out quite safely in the majority of cases.

When the clinical situation fails to respond to this conservative management, particularly if there is increasing pain and fever, an empyema or gangrene of the gall bladder may have occurred. In this circumstance urgent imaging (transabdominal ultrasound or CT scan) is required to define the pathology. Surgical intervention is usually required although a radiologically placed gall bladder drain can be used as a temporizing measure for the management of an empyema.

Specific complications of cholecystectomy include a biliary leak either from the cystic duct or from the gall bladder bed. Injury to the bile duct itself occurs in up to 0.5% of laparoscopic operations and may have serious long-term sequelae in the form of a bile duct stricture and secondary biliary liver injury. There is an overall mortality of 0.2%.

Stone dissolution and shock wave lithotripsy

These non-surgical techniques for the management of gall bladder stones are infrequently used but still have a role in a few highly selected patients who may not be fit for cholecystectomy or have declined the surgical option.

Pure or near-pure cholesterol stones can be solubilized by increasing the bile salt content of bile. Oral chenodeoxycholic acid and ursodeoxycholic acid have been successfully utilized. The approach requires long-term therapy and the recurrence rate of gallstones is high when therapy is stopped. Additional pharmacological tools for treating cholesterol gallstones include cholesterol-lowering agents that inhibit hepatic cholesterol synthesis (statins) or intestinal cholesterol absorption (ezetimibe), or drugs acting on specific nuclear receptors involved in cholesterol and bile acid homeostasis.

The post-cholecystectomy syndrome

This refers to right upper quadrant pain, often biliary in type, which occurs a few months after the cholecystectomy but may be delayed for a number of years. The patients often comment that the pain is identical to that for which the original operation was carried out. In many cases this syndrome is related to functional large bowel disease with colonic spasm at the hepatic flexure (hepatic flexure syndrome). In a small proportion of patients the pain is a result of a retained common bile duct stone. In a further minority of patients, hypertension of the sphincter of Oddi is a potential cause. This is most likely in patients with abnormal liver biochemistry and dilatation of the common bile duct (on ultrasound) during episodes of pain (and in the absence of a documented retained stone). The diagnosis is confirmed by pressure measurements of the sphincter of Oddi, and the condition can be successfully managed by endoscopic sphincterotomy (see below).

Common bile duct stones

The classical features of common bile duct (CBD) stones are biliary colic, fever and jaundice (acute cholangitis). This triad is only present in the minority of patients. Abdominal pain is the most common symptom and has the typical features of biliary colic (see above). Jaundice is a variable accompaniment and is almost always preceded by abdominal pain. A patient with bile duct stones may experience sequential episodes of pain, only some of which are accompanied by jaundice. In contrast to malignant bile duct obstruction, the level of jaundice associated with CBD stones characteristically tends to fluctuate. In the elderly or immunocompromised patient cholangitis may present with very nonspecific symptoms and only associated abnormal liver biochemistry may point to the diagnosis.

Fever is only present in a minority of cases but indicates biliary sepsis and sometimes an associated septicaemia. The presence of such biliary sepsis is a significant adverse prognostic factor.

A minority of patients with bile duct stones are discovered incidentally during imaging for gall bladder disease. A total of 15% of patients undergoing cholecystectomy will have stones within the bile duct only detected at the time of operative cholangiography. The frequency of asymptomatic bile duct stones resulting in complications is not well documented. It is likely that many such stones will pass into the duodenum without causing symptoms. However, the potential for serious complication is well recognized and in most circumstances incidentally identified bile duct stones are removed (see below).

Physical examination

If the patient is examined between episodes, there may be no abnormal physical finding. During a symptomatic episode the patient may be jaundiced with a fever and associated tachycardia. There is tenderness in the right upper quadrant varying from mild to extremely severe.

More widespread abdominal tenderness extending from the epigastrium to the left upper quadrant, associated with distension, may indicate associated stone-related pancreatitis (see below).

Investigations

Full blood count is usually normal in the presence of uncomplicated bile duct stones.

Full blood count is usually normal in the presence of uncomplicated bile duct stones.

An elevated neutrophil count and raised inflammatory markers (ESR and CRP) are frequent accompaniments of cholangitis.

An elevated neutrophil count and raised inflammatory markers (ESR and CRP) are frequent accompaniments of cholangitis.

The raised serum bilirubin tends to be mild and often transient. Very high concentrations of bilirubin (>200 µmol/L) almost always reflect complete bile duct obstruction.

The raised serum bilirubin tends to be mild and often transient. Very high concentrations of bilirubin (>200 µmol/L) almost always reflect complete bile duct obstruction.

Serum alkaline phosphatase and γ-glutamyl transpeptidase are similarly elevated in proportion to the degree of hyperbilirubinaemia.

Serum alkaline phosphatase and γ-glutamyl transpeptidase are similarly elevated in proportion to the degree of hyperbilirubinaemia.

Aminotransferase levels are usually mildly elevated but with complete bile duct obstruction there may be very marked rises to 10–15 times the normal value. The alanine aminotransferase is characteristically higher than the aspartate aminotransferase. These high levels may lead to an initial misdiagnosis of a hepatitic process.

Aminotransferase levels are usually mildly elevated but with complete bile duct obstruction there may be very marked rises to 10–15 times the normal value. The alanine aminotransferase is characteristically higher than the aspartate aminotransferase. These high levels may lead to an initial misdiagnosis of a hepatitic process.

Serum amylase levels are often mildly elevated in the presence of bile duct obstruction but are markedly so if stone-related pancreatitis has occurred.

Serum amylase levels are often mildly elevated in the presence of bile duct obstruction but are markedly so if stone-related pancreatitis has occurred.

Prothrombin time may be prolonged if bile duct obstruction has occurred; this reflects decreased absorption of vitamin K.

Prothrombin time may be prolonged if bile duct obstruction has occurred; this reflects decreased absorption of vitamin K.

Transabdominal ultrasound is the initial imaging technique of choice.

Bile duct obstruction is characterized by dilatation of intrahepatic biliary radicles, which are usually easily detected by the ultrasound scan. It may, however, not be possible to identify the cause of obstruction. Stones situated in the distal common bile duct are poorly visualized by transabdominal ultrasound and up to 50% are missed. The detection of stones within the gall bladder is poorly predictive as to the cause of bile duct obstruction. Asymptomatic gallstones are common (up to 15%) in patients who are 65 years and older. Conversely, in 5–10% of patients with bile duct stones, no calculi can be seen within the gall bladder.

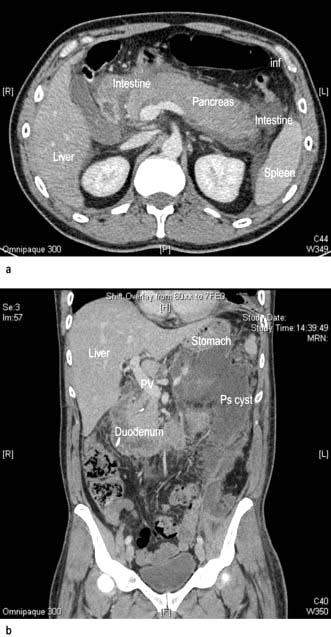

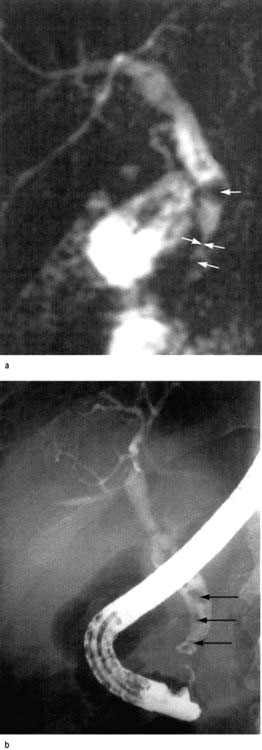

Magnetic resonance cholangiography (MRC) delineates the fluid column within the biliary tree and is a sensitive technique for the detection of common bile duct stones in the presence of a dilated duct. The technique may be less accurate in the absence of duct dilatation (see the role of endoscopic ultrasound, below) (Fig. 7.32).

Figure 7.32 (a) A magnetic resonance cholangiogram in a patient presenting with abdominal pain and jaundice. This shows evidence of a distal common bile duct stricture with a stone in the bile duct proximal (arrows). (b) An ERCP in the same patient confirming the details identified in the MRCP scan. The stones (arrowed) were removed at the time of the ERCP after initial dilatation of the stricture.

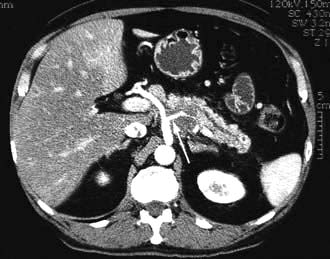

CT scanning is an alternative way to detect bile duct dilatation. Opaque stones are more readily identifiable within the bile duct than radiolucent cholesterol stones. CT scanning also provides a means of excluding other causes of bile duct obstruction such as carcinoma of the head of the pancreas.

Endoscopic ultrasound scanning (Figs 7.33, 7.34) has enabled high-resolution imaging of the common bile duct, gall bladder and pancreas, although unlike the preceding imaging techniques it is an invasive procedure. The endoscopic ultrasound probe in the duodenum is in close proximity with the distal common bile duct and hence can identify the majority of stones at this level.

Figure 7.33 An endoscopic ultrasound scan with the probe in the first part of the duodenum identifying the gall bladder (GB) and multiple small echo-poor stones within (microlithiasis). The patient had presented with recurrent episodes of unexplained abdominal pain.

Figure 7.34 An endoscopic ultrasound scan with the probe within the first part of the duodenum (D1) and defining the common bile duct (BD) and a stone (S) clearly identified within the lumen of the common bile duct.

This technique is particularly useful for identifying small calculi (microcalculi), in a non-dilated common bile duct.

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiography (ERC)

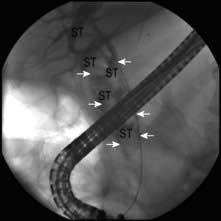

In experienced hands, visualization of the common bile duct will be successful in 98% of cases, providing good documentation of bile duct stones (Fig. 7.32, Fig. 7.35). However, microcalculi can still be missed. ERC is an invasive procedure with recognized risks. In almost all circumstances this is a therapeutic tool used to remove the stones that have been identified by the investigations described above.

Figure 7.35 An ERCP carried out in a patient with abdominal pain, fluctuating jaundice and fever. The cholangiogram shows a markedly dilated biliary tree (arrowed) with multiple large stones within (ST). These stones were removed at the time of ERCP using a mechanical lithotripsy device to crush the stones before removing from the duct by means of balloon and basket retrieval.

Differential diagnosis

Cholangitis may occur independently of gallstones in any condition associated with impaired biliary drainage. It is commonly associated with conditions such as primary sclerosing cholangitis and Caroli’s syndrome. Cholangitis may also complicate post-traumatic or surgery-associated bile duct strictures. It is unusual in malignant bile duct obstruction unless there has been prior endoscopic or surgical intervention. Jaundice may also be a feature of acute cholecystitis in the absence of bile duct stones. A stone impacted in the cystic duct may compress and obstruct the bile duct (Mirizzi’s syndrome). Common bile duct stones may produce pain, but in the absence of jaundice, the differential diagnosis is that of biliary colic (see above).

Management

Acute cholangitis has a high morbidity and mortality, particularly in the elderly. Successful management depends on intravenous antibiotics (see as for acute cholecystitis), and urgent bile duct drainage. In most circumstances this is achieved by the endoscopic retrograde approach. Access to the bile duct is achieved by sphincterotomy, and thereafter the stones can be removed either by balloon or basket catheters. In the severely ill patient a piece of plastic tubing (termed a stent) can be inserted into the bile duct to maintain bile drainage without the need to remove the stones; hence minimizing the time period to complete the procedure. The residual stones can then be removed endoscopically when the patient has recovered from the episode. If endoscopic drainage is not available or prevented by inability to access the second part of the duodenum then a radiologically placed percutaneous biliary drain represents an alternative management option. Surgical drainage has been associated with a high mortality and is now limited to those very few cases which cannot be managed by the endoscopic or percutaneous approach.

Urgent endoscopic bile duct clearance is also indicated in some patients with acute gallstone pancreatitis (see below). Patients who have retained common bile duct stones after a previous cholecystectomy are also optimally managed by endoscopic clearance. Patients shown to have common bile duct stones as well as gall bladder stones may be treated by two different approaches:

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy which can also include exploration of the CBD via the cystic duct or by direct choledochotomy. By using these techniques the laparoscopist can extract stones from the CBD. This, however, prolongs the procedure, particularly in the presence of large stones or biliary sepsis.

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy which can also include exploration of the CBD via the cystic duct or by direct choledochotomy. By using these techniques the laparoscopist can extract stones from the CBD. This, however, prolongs the procedure, particularly in the presence of large stones or biliary sepsis.

Endoscopic approach either immediately before or after the cholecystectomy. Removal of CBD stones by this method is the preferred way in the UK. Large bile duct stones (>10 mm) may present a significant challenge to endoscopic removal. Mechanical lithotripsy facilitates stone fragmentation and removal into the duodenum. Both extracorporeal and intraductal shock wave stone fragmentation has also been used.

Endoscopic approach either immediately before or after the cholecystectomy. Removal of CBD stones by this method is the preferred way in the UK. Large bile duct stones (>10 mm) may present a significant challenge to endoscopic removal. Mechanical lithotripsy facilitates stone fragmentation and removal into the duodenum. Both extracorporeal and intraductal shock wave stone fragmentation has also been used.

Complications of gallstones

Acute cholecystitis and acute cholangitis have been discussed (p. 353).

Acute cholecystitis and acute cholangitis have been discussed (p. 353).

Gallstone-related pancreatitis is discussed on page 363.

Gallstone-related pancreatitis is discussed on page 363.

Gallstones can occasionally erode through the wall of the gall bladder into the intestine giving rise to a biliary enteric fistula. Passage of a gallstone through into the small bowel can give rise to an ileus or true obstruction.

Gallstones can occasionally erode through the wall of the gall bladder into the intestine giving rise to a biliary enteric fistula. Passage of a gallstone through into the small bowel can give rise to an ileus or true obstruction.

There is little evidence that gallstones are associated with an increased risk of adenocarcinoma of the gall bladder (p. 357).

There is little evidence that gallstones are associated with an increased risk of adenocarcinoma of the gall bladder (p. 357).

Miscellaneous conditions of the biliary tract

Gall bladder

There are a number of non-calculous conditions of the gall bladder, some of which have been associated with symptoms.

Non-calculous cholecystitis

Almost 10% of gall bladders removed for biliary symptoms are shown to have chronic inflammation within the wall but an absence of gallstones. Such cases are described as non-calculous cholecystitis. In many instances the gall bladder inflammation is minor and of doubtful significance. In a minority of cases non-calculous cholecystitis is characterized by severe inflammation frequently associated with gall bladder perforation. This condition is characteristically found in an elderly and critically ill group of patients. Chemical inflammation of the gall bladder may also occur from reflux of pancreatic enzymes back into the biliary tree, usually through the common channel at the ampulla of Vater. Bacterial and viral infections of the gall bladder have been recognized as a cause of non-calculous cholecystitis.

The decision to carry out cholecystectomy in the absence of defined gall bladder stones should be guided by the specific features of the history and whether there is evidence of a diseased gall bladder wall on ultrasound scanning.

Cholesterolosis of the gall bladder

In cholesterolosis, cholesterol and other lipids are deposited in macrophages within the lamina propria of the gall bladder. These may be diffusely situated, giving a granular appearance to the gall bladder wall, or on occasions more discrete, giving a polypoid appearance (see below). Cholesterolosis of the gall bladder may co-exist with gallstones but occurs independently. Some degree of cholesterolosis may be found in up to 25% of autopsies in an elderly population. It is doubtful whether this is a cause of symptoms.

Adenomyomatosis of the gall bladder

Adenomyomatosis is a gall bladder abnormality characterized by hyperplasia of the mucosa, thickening of the muscle wall and multiple intramural diverticula (the so-called ‘Rokitansky–Aschoff sinuses’).

The condition is usually detected as an incidental finding during investigation for possible gall bladder disease. It has been suggested that this condition is secondary to increased intraluminal gall bladder pressure but this is not proven. Gallstones may frequently co-exist but there is no evidence to support a direct relationship.

It is unlikely that adenomyomatosis alone is a cause of biliary symptoms.

Chronic cholecystitis

There are no symptoms or signs that can conclusively be shown to be due to chronic cholecystitis. Symptoms attributed to this condition are vague, such as indigestion, upper abdominal discomfort or distension. There is no doubt that gall bladders studied histologically can show signs of chronic inflammation, and occasionally a small, shrunken gall bladder is found either radiologically or on ultrasound examination. However, these findings can be seen in asymptomatic people and therefore this clinical diagnosis should not be made. Most patients with chronic right hypochondrial pain suffer from functional bowel disease (p. 230).

Extrahepatic biliary tract

Primary sclerosing cholangitis (see p. 334)

In up to 40% of patients with PSC the clinical course is influenced by a dominant extrahepatic/hilar stricture. This is relevant in those patients who do not have established advanced liver involvement in whom maintaining bile flow can protect the liver from secondary biliary injury. Drainage with a surgical hepaticojejunostomy has been beneficial in some cases. More recently repeated endoscopic balloon dilatation and temporary stenting of the extrahepatic/hilar stricture has been reported with prolonged benefit.

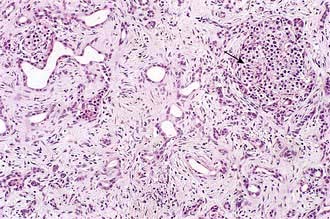

Autoimmune cholangitis

Immunoglobulin (Ig)G4-associated cholangitis is the biliary manifestation of a multisystem fibroinflammatory disorder in which affected organs have a characteristic lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate rich in IgG4-positive cells. The original description of this condition was in the context of autoimmune pancreatitis (see p. 365). The large majority of cases are recognized in middle-aged or elderly men and presentation is varied depending upon the systems involved but includes abdominal pain and jaundice. Both intra- and extrahepatic biliary strictures maybe seen and the findings may be misinterpreted as representing cholangiocarcinoma. The diagnosis relies upon clinical suspicion and confirmation of an elevated serum IgG4 level and a typical lymphocytoplasmic infiltrate on histological examination of involved tissue. The condition is almost always responsive to steroids but can lead to hepatic failure.

Choledochal malformation (cysts)

Congenital malformation of the bile ducts may occur at all levels of the biliary tree, although most commonly are extrahepatic. The resulting dilatation of the choledochus may be saccular, diverticular or of fusiform configuration. In many cases there is associated pancreatobiliary malunion with the pancreatic duct draining directly into the common bile duct. The majority of symptomatic cases present in childhood with features of cholangitis. The formation of stones and sludge within the cystic segment may predispose to acute relapsing pancreatitis. In adult life, choledochal cysts may be a differential diagnosis in patients presenting with symptoms suggestive of bile duct stones. The cyst must be fully resected to avoid the recurrent biliary complications as well as averting the risk (approximately 15%) of subsequent cholangiocarcinoma.

Benign bile duct strictures

Benign strictures area a recognized complication of biliary surgery. This may include inadvertent stapling of the duct or as a consequence of ischaemic injury (often in association with a bile duct leak). A stricture may also occur at the level of a bile duct anastomosis either enteric or duct to duct. A bile duct stricture can also result from major trauma to the right upper quadrant. The distal common bile duct is commonly compressed in the presence of chronic pancreatitis (see below).

In most cases the initial therapy will be endoscopic including balloon dilatation of the stricture and temporary bile duct stenting (see below). This may provide definitive management but in some cases surgical intervention is required.

Haemobilia

Haemobilia is the term used to describe bleeding into the biliary tree. This may be as a consequence of liver trauma or as a complication of liver surgery. Biopsy of the liver is also a well-recognized cause. The end result is a fistula between a branch of the hepatic artery and an intrahepatic bile duct.

Haemobilia may be a cause of significant gastrointestinal blood loss and should be suspected when melaena is accompanied by right-sided upper abdominal pain and jaundice. However, the bleeding may occur without any overt biliary symptoms. If the diagnosis is suspected, bleeding may be managed by occlusion of the feeding artery by thrombosis performed radiologically.

Some patients will require surgery to control the bleeding point.

Tumours of the biliary tract

Gall bladder polyps

Polyps of the gall bladder are a common finding, being seen in approximately 4% of all patients referred for hepatobiliary ultrasonography. The vast majority of these are small (<5 mm), are non-neoplastic and are inflammatory in origin or composed of cholesterol deposits (see above). Adenomas are the most common benign neoplasm of the gall bladder. Only a proportion of these have a cancerous potential. The only reliable means of defining those at risk is polyp size (>10 mm). Cholecystectomy is recommended for any polyp approximating to 1 cm in diameter or larger.

Primary cancer of the gall bladder

Adenocarcinoma of the gall bladder represents 1% of all cancers. The mean age of occurrence is in the early 60s, with a women to men ratio of 3 : 1. Gallstones have been suggested as an aetiological factor but this relationship remains unproven. Diffuse calcification of the gall bladder (porcelain gall bladder), considered to be the end stage of chronic cholecystitis, has also been associated with cancer of the gall bladder and is an indication for early cholecystectomy. Adenomatous polyps of the gall bladder in excess of 10 mm in diameter are also recognized as premalignant lesions (see above).

Carcinoma of the gall bladder is often detected at the time of planned cholecystectomy for gallstones and in such circumstances resection of an early lesion may be curative. Early lymphatic spread to the liver and adjacent biliary tract precludes curative resection in more advanced lesions. There are no proven chemotherapeutic agents for carcinoma of the gall bladder. A small proportion of cases are sensitive to radiotherapy but the overall 5-year survival is less than 5%.

Cholangiocarcinoma (see also p. 348)

Cancer of the biliary tree may be intra- or extrahepatic. These malignancies represent approximately 1% of all cancers. A number of associations have been identified such as that with choledochal malformation (see above), and with primary sclerosing cholangitis. Chronic infection of the biliary tree with, e.g. Clonorchis sinensis, has also been implicated. The bile duct malignancy usually presents with jaundice and may be suspected by imaging, initially ultrasound and thereafter CT and in particular magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP). Histological/cytological diagnosis may be difficult to attain because the malignant cells are often few in number and contained within a dense stroma. Endoscopically obtained cytology specimens have only 30% sensitivity. The can be enhanced by using techniques such as fluorescent in situ hybridization and digital image analysis. Improved techniques of endoscopic cholangioscopy have enabled direct visualization of the lesions and allowing targeted biopsy.

The disease spread is usually by local lymphatics or local extension. Cholangiocarcinoma of the common bile duct may be resectable at presentation but local extension precludes such management in the majority of more proximal lesions. Localized disease justifies an aggressive surgical approach including partial hepatic resection. Chemo-radiation has been used to treat localized small hilar cholangiocarcinoma and in a few cases has facilitated successful liver transplantation, but the carcinoma recurs.

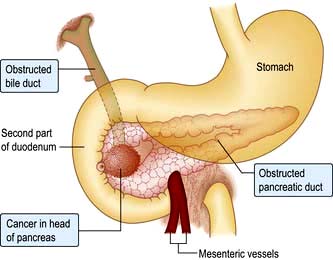

Secondary malignant involvement of the biliary tree

Carcinoma of the head of the pancreas frequently presents with common bile duct obstruction and jaundice. Metastases to the bile ducts from distant cancers are uncommon. Melanoma is the most frequent neoplasm to do so.

Other carcinomas that have caused bile duct metastases, in order of frequency, are those arising in the lung, breast and colon as well as those from the pancreas (metastatic as compared to direct infiltration). Infiltration of the bile duct is not uncommon in disseminated lymphomatous disease.

Palliation of malignant bile duct obstruction

A small proportion of cholangiocarcinomas are surgically resectable, more commonly those in the distal bile duct as compared to the hilar region. All patients must be fully screened for operability using the imaging techniques described above. However, in the greater proportion of patients the treatment is palliative. Relief of bile duct obstruction has been shown to improve quality of life considerably and with pain control is the major end point of palliation. In recent years, endoscopic techniques have allowed the insertion of stents into the biliary tree to re-establish bile flow. The initial use of plastic stents has largely been replaced by self-expanding metal stents which have considerably longer periods of patency (Fig. 7.36). In the small proportion of patients in whom bile duct drainage is not possible endoscopically, the percutaneous route offers an alternative method of stent placement. There is some evidence of benefit from the use of photodynamic therapy in those patients in whom biliary drainage has been achieved. This technique involves the use of a porphyrin derivative to sensitize the malignant cells prior to activation by an endoscopically placed laser probe. The aim is to provide local tumour destruction and maintain bile duct patency.

Figure 7.36 An ERCP in a patient presenting with painless jaundice. (a) There is a tight stricture in the mid-common bile duct (CBD) and extending proximally over 4 cm (extent defined by arrows). The intrahepatic ducts (IHD) proximally are dilated. A catheter has been place endoscopically across the stricture. (b) A self-expanding metal stent has been placed across the stricture and released. The stent is compressed at the level of the stricture but will open fully over 24 h. The contrast in the intrahepatic ducts (IHD) has largely drained through the stent. The distal margin of the stent is in the duodenum.