The lymphomas

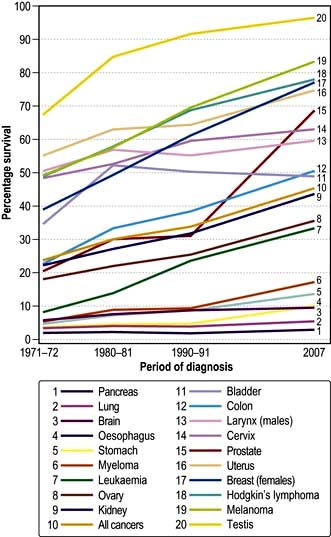

The lymphomas are malignancies of the lymphoid system and hence may arise at any site where lymphoid tissue is present. Certain subtypes have increased in frequency over the past 50 years for reasons which are not clear, the overall incidence being 15–20 per 100 000 population making them the fifth most common malignancy in the Western world. Most commonly patients have peripheral lymphadenopathy or symptoms due to occult lymph nodes, although approximately 20% arise at primary extra-nodal sites. A relatively small proportion present with lymphoma-associated ‘B’ symptoms of weight loss, fever and sweats. The natural history and clinical course are determined by the pathological subtype, classified by histological, immunological and molecular criteria, the distribution of the disease (‘Stage’), nonspecific prognostic features and general co-morbidity.

A significant proportion of patients are cured and many others are helped both in terms of quality and length of life.

The WHO classification of Tumours of Haematopoetic and Lymphoid Tissues primarily distinguishes Hodgkin’s lymphoma from non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, an umbrella term covering a multiply subclassified spectrum of B- and T-cell malignancies, reflecting the stage of lymphoid development at which they arise. Thus, lymphoblastic lymphoma and lymphoblastic leukaemia are considered as a single entity, as are small lymphocytic lymphoma and chronic lymphatic leukaemia, both discussed in the section above.

FURTHER READING

Canellos GP, Lister TA, Young BD (eds). The Lymphomas, 2nd edn. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2006.

Magrath IT, Boffetta P, Potter M (eds). The Lymphoid Neoplasms, 3rd edn. London: Hodder Arnold; 2010.

Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL et al. WHO Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues, 4th edn. Geneva: WHO; 2008.

Overall management strategy common to all lymphomas

A suspected diagnosis of lymphoma should always be confirmed by an excision biopsy of the relevant tissue large enough to allow histological, immunological and molecular analysis. Cutting needle biopsy is an acceptable substitute for biopsy of impalpable, ‘occult’ disease, but fine needle aspiration is inadequate. The opinion of an expert haemato-pathologist is essential.

Investigation

The diagnosis having been established, the treatment strategy and details will depend on the outcome of investigations that are common to all the lymphomas. These investigations are conducted to provide a basis for prognostication and treatment decisions, against which the outcome of treatment may be assessed (Table 9.22), ‘stage’ being assigned notionally to the modification of the Ann Arbor classification for all nodal lymphomas despite the fact it was planned only for Hodgkin’s disease.

Table 9.22 Investigation of the patient with lymphoma

The tests in Table 9.22 are essential for planning specific therapy. The serum uric acid is helpful, particularly in those lymphomas in which there is risk of tumour lysis syndrome (see p. 449), tests of cardiac function when potentially cardiotoxic chemotherapy is to be recommended, as well as HIV, hepatitis B and C status.

Upon completion of these investigations, within a maximum of 2 weeks, a treatment plan should be presented to the patient. Central to this is the expectation of success and whether treatment is given with curative or palliative intent. The options will range from expectant management to immediate intervention with intensive therapy, itself potentially life-threatening. A decision to ‘treat’ having been made, a course of treatment will begin, during which benefit will be assessed at appropriate intervals and subsequent to which complete re-evaluation (‘re-staging’) will be performed. Depending on the outcome, future plans will be made. In the event of a decision to stop treatment, surveillance will in the first instance, be close, the interval between attendances being extended with the passage of time. Beyond 5 years, the focus of attention is upon the possible long-term consequences of therapy, rather than the disease itself. For those for whom the initial therapy has been less successful than wished, management will be dictated by individual circumstances. As conventional treatment becomes exhausted, experimental therapy may be broached.

Hodgkin’s lymphoma (Hl)

HL occurs with an incidence of approximately 3 per 100 000 in the Western world; there is a male predominance of approximately 1.3 : 1. The majority of cases occur between the ages of 16 and 65, with a peak in the 3rd decade. The incidence is stable.

Aetiology

There is epidemiological evidence linking previous infectious mononucleosis with HL; up to 40% of patients with HL have increased EBV antibody titres at the time of diagnosis and EBV DNA has been demonstrated in tissue from patients with HL. These data suggest a role for EBV in pathogenesis. Other viruses have not been detected. Other environmental and occupational exposures to pathogens have been postulated.

Diagnosis

Hodgkin’s lymphoma is subclassified according to the WHO classification (Table 9.23) into:

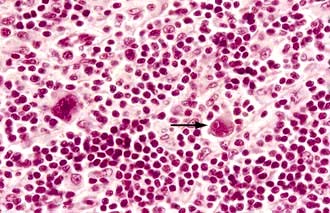

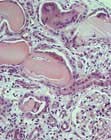

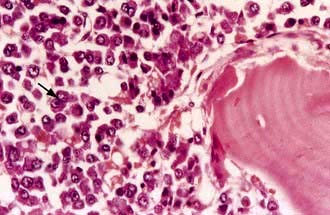

1. Classical Hodgkin’s lymphoma (cHL), the hallmark of which is the Reed–Sternberg cell (Fig. 9.17), accounting for 90–95% of cases and which is further subdivided into four distinct categories

2. Nodular lymphocyte predominant HL (NLPHL), characterized by the Reed–Sternberg cell variant, the ‘popcorn cell’.

Table 9.23 Hodgkin’s lymphoma – pathological classification

5% |

From Harris NL, Jaffe ES, Diebold J et al. 1999 World Health Organization classification of neoplastic diseases of the hematopoietic and lymphoid tissues: report of the clinical advisory committee meeting – Airlie House, Virginia, November 1997. J Clin Oncol 17:3835–49, with permission.

Clinical features

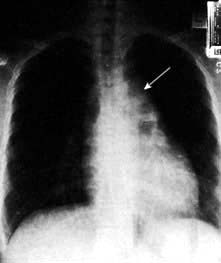

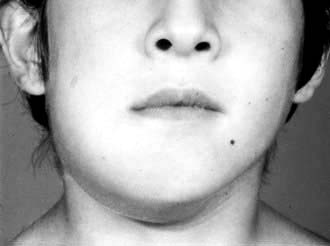

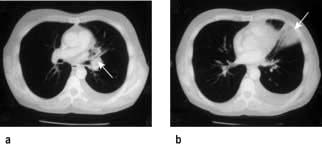

The commonest presentation of HL is painless cervical lymphadenopathy, commonly described in examination as ‘rubbery’. Other causes of cervical lymphadenopathy are shown in Table 9.24. A smaller proportion present with disease localized to the mediastinum (often young women), with cough due to mediastinal lymphadenopathy (Fig. 9.18), others with ‘generalized disease’, including hepatosplenomegaly and constitutional ‘B’ symptoms. Other less common symptoms, undoubtedly associated with Hodgkin’s lymphoma, but not recognized in the staging classification, are pruritus and alcohol-related pain at the site of lymphadenopathy.

Table 9.24 Cervical lymph node enlargement–differential diagnosis

Infections Acute Pyogenic infections Infective mononucleosis Toxoplasmosis Cytomegalovirus infection Infected eczema Cat scratch fever Acute childhood exanthema Chronic Tuberculosis Syphilis Sarcoidosis HIV infectionAutoimmune rheumatic disease Rheumatoid arthritisDrug reactions Phenytoin |

Primary lymph node malignancies Hodgkin’s lymphoma Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma Chronic lymphocytic leukaemia Acute lymphoblastic leukaemiaSecondary malignancies Nasopharyngeal, oropharyngeal Thyroid Laryngeal Lung Melanoma Breast StomachMiscellaneous Kawasaki’s syndrome Kikuchi’s disease (histiocytic necrotizing lymphadenitis) Castleman’s disease |

Investigation

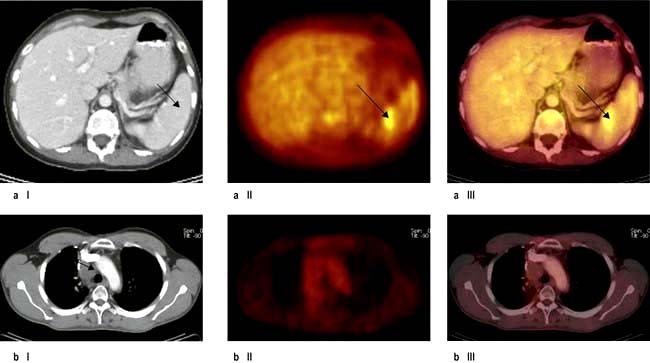

This is summarized in Table 9.22. Bone marrow biopsy is only indicated in patients with clinically advanced disease (stage III, IV), those with ‘B’ symptoms and those who are HIV-positive. The clinical utility of the PET scan is becoming established in the management of Hodgkin’s lymphoma (Fig. 9.19).

‘Stage’ is currently assigned according to the Cotswolds modification of the Ann Arbor Classification, although this is under review (Table 9.25). The Hasenclever score is used for prognostication (Box 9.8); however its relevance to treatment planning is limited because of the very small number of patients at high risk of standard treatment failure. On the basis of ‘stage’ and other prognostic factors, patients with HL are divided into three groups (Table 9.26).

Table 9.25 Cotswolds modification of Ann Arbor staging classification of Hodgkin’s lymphoma

| Stage | Description |

|---|---|

Stage I |

Involvement of a single lymph-node region or lymphoid structure (e.g. spleen, thymus, Waldeyer’s ring) or involvement of a single extralymphatic site |

Stage II |

Involvement of two or more lymph-node regions on the same side of the diaphragm (hilar nodes, when involved on both sides, constitute stage II disease); localized contiguous involvement of only one extranodal organ or site and lymph-node region(s) on the same side of the diaphragm (IIE). The number of anatomic regions involved should be indicated by a subscript (e.g. II3) |

Stage III |

Involvement of lymph-node regions on both sides of the diaphragm (III), which may also be accompanied by involvement of the spleen (IIIS) or by localized involvement of only one extranodal organ site (IIIE) or both (IIISE) |

III1 |

With or without involvement of splenic, hilar, coeliac or portal nodes |

III2 |

With involvement of para-aortic, iliac and mesenteric nodes |

Stage IV |

Diffuse or disseminated involvement of one or more extranodal organs or tissues, with or without associated lymph-node involvement |

Designations applicable to any disease state |

|

A |

No symptoms |

B |

Fever (temperature >38°C), drenching night sweats, unexplained loss of >10% of body weight within the previous 6 months |

X |

Bulky disease (a widening of the mediastinum by more than one-third of the presence of a nodal mass with a maximal dimension >10 cm) |

E |

Involvement of a singe extranodal site that is contiguous or proximal to the known nodal site |

From Diehl V, Thomas RK, Re D et al. Hodgkin’s lymphoma – diagnosis and treatment. Lancet Oncology 2004; 5:19–26 with permission from Elsevier.

![]() Box 9.8

Box 9.8

Advanced stage Hodgkin’s lymphoma (Hasenclever score)

Clinical prognostic factors

| Score | 0 | 1 |

|---|---|---|

Serum albumin |

Normal |

<40 g/L |

Haemoglobin |

>105 g/L |

<105 g/L |

Age |

<45 |

>45 |

Sex |

Female |

Male |

Stage |

<IV |

IV |

Leucocytosis |

<15 × 109/L |

>15 × 109/L |

Lymphopenia |

>0.6 × 109/L |

<0.6 × 109/L |

Cumulative score |

Freedom from progression at 5 years |

Frequency |

Score 0 |

84% |

7% (of all patients) |

Score 1 |

77% |

22% |

Score 2 |

67% |

29% |

Score 3 |

60% |

28% |

Score 4 |

51% |

12% |

Score 5 |

42% |

7% |

Table 9.26 Hodgkin’s lymphoma prognostic groups

Early favourable |

Stage I + II without unfavourable prognostic factors |

Early unfavourable |

Stage I + II with unfavourable factors |

Advanced |

The remainder |

Initial management

Treatment is aimed towards a curative intent with expectation of success. However, in patients with NLPHL who usually present with stage I disease with longstanding lymphadenopathy, an expectant policy with close surveillance, is followed. Older patients, with or without co-morbidity, require considerable modification of therapy and there is an expectation of success. Patients with HIV infection should be managed, in conjunction with their HIV clinicians, in the same way as those who are seronegative.

Treatment

Early stage, ‘low risk’

‘Moderate’ chemotherapy, comprising 2–4 cycles of doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine and dacarbazine (ABVD), non-sterilizing and of a low second cancer risk, followed by involved field irradiation (20–30 Gy) has replaced large field irradiation (p. 435), with 90% being cured. Current trials are evaluating the role of PET scanning to see if patients who become ‘PET’ negative’ after chemotherapy can be spared irradiation altogether.

Advanced disease (including locally advanced unfavourable early stage)

This is also curable for a significant proportion of patients with a median survival well exceeding 5 years for 50–60% of patients. Cyclical chemotherapy with 6–8 cycles of ABVD with involved field irradiation to sites which were initially bulky, or at which there is ‘persistent disease’ after chemotherapy, is standard. Increasingly, the data from studies incorporating PET scanning both part way through and after planned chemotherapy have shown that PET–ve masses are likely to represent fibrous tissue and that in this situation irradiation may be omitted.

The major short-term toxicity relates to myelosuppression and mucositis, the mortality being no more than 1% and the long-term risks being to the heart and lungs. Infertility and second malignancy are uncommon.

The above approach fails for about 25% of patients. More intensive treatment programmes, e.g. BEACOPP with additional etoposide (E) procarbazine (P) and prednisolone (P), have been tested with an overall increase in efficacy, but with greater toxicity profiles (and expense). It remains a challenge to identify those who will be ‘ABVD failures’ at initial presentation. An alternative is to develop ‘risk-adapted’ therapy, based on the response to the first two cycles of therapy, again with PET scanning and escalate to more intensive therapy in those in whom the response is deemed inadequate.

Management of failure of initial therapy

This has become a declining problem because of improvements in the outcome of first-line therapy. The median survival from first recurrence is more than 10 years, possibly being influenced by the duration of the first remission; it may not be so good if failure occurs after very intensive therapy. Second and third remissions may be achieved with ‘appropriate’ re-induction therapy, consolidated, if possible with an autograft. Registry data suggest this may be curative for up to 50%, but follow-up only extends to 15 years.

Experimental approaches

With such excellent results of first- and second-line conventional therapy, experimental treatment is seldom required. The antigen-targeted immunoconjugate, anti-CD-30-auristatin (SGN-35, brentuximab) has shown such efficacy in phase II trials and the histone deacetylase inhibitor (HDAC) panobinostat also has potential. Allogeneic haemopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) following myeloablative conditioning has high treatment-related mortality and morbidity. Reduced intensity conditioning HSCT, followed if necessary by donor lymphocyte infusion, is being investigated.

Non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas (NHL)

Defined by the WHO classification (Table 9.27), approximately 80% of NHL are of B-cell origin and 20% of T-cell origin, there being considerable geographical variation. The incidence has increased, not necessarily for all subtypes, from 5 to 15 per 100 000 per year in the last half century.

Table 9.27 Modified WHO classification of lymphoid neoplasms other than ALL (2008)

B-cell lymphomas |

|

Precursor B-cell neoplasm |

B-cell lymphoblastic lymphoma/leukaemia (highly aggressive) |

Mature B-cell lymphoma |

Chronic lymphocytic leukaemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma |

B-cell prolymphocytic leukaemia |

|

Splenic marginal zone lymphoma |

|

Hairy cell leukaemia |

|

Lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma |

|

Extranodal marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT-lymphoma) |

|

Nodal marginal zone B-cell lymphoma |

|

Follicular lymphoma (aggressive) |

|

Mantle cell lymphoma |

|

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (aggressive) |

|

Mediastinal (thymic) large B-cell lymphoma |

|

Intravascular large B-cell lymphoma |

|

Primary effusion lymphoma |

|

Burkitt’s lymphoma/leukaemia (highly aggressive) |

|

T/NK cell lymphomas |

|

Precursor T-cell neoplasm |

T-cell lymphoblastic leukaemia/lymphoma (highly aggressive) |

Mature T/NK cell lymphoma |

T-cell prolymphocytic leukaemia |

T-cell large granular lymphocytic leukaemia |

|

Chronic/lymphoproliferative disorder of NK cells |

|

Aggressive NK cell leukaemia |

|

Adult T-cell leukaemia/lymphoma (very aggressive) |

|

Extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma, nasal type |

|

Enteropathy-type T-cell lymphoma |

|

Hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma |

|

Subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma |

|

Mycosis fungoides |

|

Sézary syndrome |

|

Primary cutaneous CD30+ peripheral T-cell lymphoproliferative disorders |

|

Peripheral T-cell lymphoma, unspecified (aggressive) |

|

Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma |

|

Anaplastic large cell lymphoma (aggressive) ALK positive |

|

Anaplastic large cell lymphoma (aggressive) ALK negative |

|

NK, natural killer.

Modified from: Jaffe ES, Harris NL, Stein H et al. (eds) World Health Organization Classification of Tumours. Pathology and Genetics of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. Lyon: IARC Press; 2008, with permission from the World Health Organization.

Aetiology

A family history is associated with a minor increase in risk of lymphoma and common genetic polymorphisms with only a small risk for an individual may be significant in population terms. Certain inherited syndromes, e.g. ataxia-telangiectasia and Wiskott–Aldrich syndrome, are associated with an increased risk of lymphoma. The human T-cell leukaemia virus type 1 (HTLV-1) is causally related to adult T-cell lymphoma/leukaemia. Helicobacter pylori is known to ‘cause’ extranodal marginal zone lymphoma in the stomach. There is a very strong epidemiological relationship between EBV and endemic Burkitt’s lymphoma and a lesser one with sporadic Burkitt’s lymphoma and Hodgkin’s lymphoma.

Immune suppression, immunosuppressant drugs, particularly as used for solid organ transplantation, and HIV infection are all associated with an increased incidence of lymphoma. Agricultural work is associated with lymphoma, but no other data show any convincing evidence of an association between occupation or lifestyle. In the majority of individual cases, the cause is unknown.

Pathogenesis

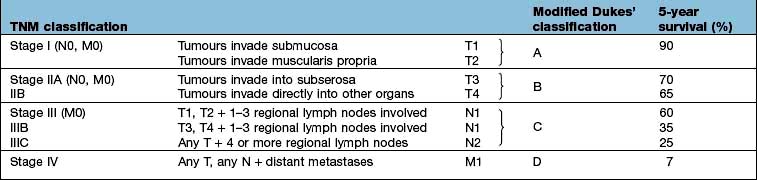

Malignant clonal expansion of lymphocytes occurs at different stages of lymphocyte development, leading to the different subtypes of lymphoma (Fig. 9.20). In general, neoplasms of non-dividing mature lymphocytes are ‘indolent’, whereas those of proliferating cells (e.g. lymphoblastic) are much more ‘aggressive’. Malignant transformation is usually due to errors in gene rearrangements which occur during the class switch, or gene recombinations for immunoglobulin and T-cell receptors. Thus, many of the errors occur within immunoglobulin loci or T- cell receptor loci. For example, an abnormal gene translocation may lead to the activation of a proto-oncogene, by moving it next to a promoter sequence for the immunoglobulin heavy chains (Ig-H).

Figure 9.20 Differentiation of T and B lymphocytes and their relationship to neoplasms. Top. T-cell differentiation. Progenitor T cells from the bone marrow enter the thymus and develop into different naive T cells. αβ T cells leave the thymus, are exposed to antigen (AG) and undergo blast transformation. They then develop into CD4+ and CD8+ effector and memory T cells. T regulatory cells are the major type of CD4+ effector cells. The other specific effector T cells are the follicular helper T cell (TFM) in the germinal centres (GC). Upon antigenic stimulation, T-cell responses to antigenic stimulation pathways of natural killer cells (NK) and γδ T cells is unknown. Bottom. B cell differentiation. Precursor B cells mature in the bone marrow and undergo apoptosis or mature to naive B cells. Following exposure to antigen and blast transformation, they develop into short-lived plasma cells or enter the germinal centre (GC). Somatic hypermutation and heavy chain class switching occur here (not shown). The transformed cells of the GC (centroblasts) undergo apoptosis or develop into centrocytes. Post-GC cells include long-lived plasma cells and memory/marginal cells. AG, antigen; DLBLC, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; CLL/SLL, chronic lymphocytic leukaemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma.

(Redrawn from information in Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL et al. WHO Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues, 4th edn. Geneva: WHO; 2008.)

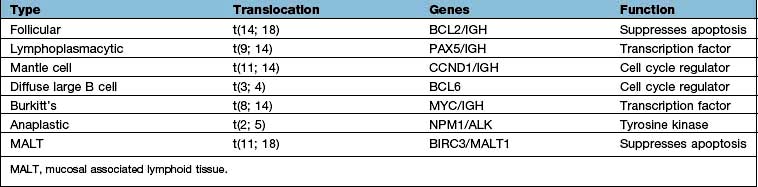

Cytogenetic features

Burkitt’s lymphoma was the first tumour in which a cytogenetic change was shown to involve the translocation of a specific gene (Table 9.28). The most frequent change is a translocation between chromosomes 8 and 14 in which the MYC oncogene is translocated from chromosome 8 to a position near the constant region of the immunoglobulin heavy chain gene on chromosome 14, resulting in upregulation of myc. Similar rearrangements involving the light chain loci are seen in the alternative Burkitt’s lymphoma translocations between chromosome 8 and either chromosome 2 or 22. Other somatic cytogenetic abnormalities associated with human lymphoma are the t(14;18) in follicular lymphoma, involving upregulation of BCL2 or the upregulation of the cell cycle regulator cyclin D1, as a result of t(11;14) in mantle cell lymphoma. Gene expression profiling and other molecular techniques are identifying new molecular subclasses of lymphoma with prognostic significance.

Specific non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas

The more common subtypes of non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas are described below.

FURTHER READING

Cheson BD, Leonard JP. Monoclonal antibody therapy for B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. N Engl J Med 2008; 359:613–626.

Good DJ, Gascoyne RD. Classification of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am 2008; 22:781–805.

Sehn LH. Optimal use of prognostic factors in non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Hematology (American Society of Hematology Education Program) 2006: 295–302.

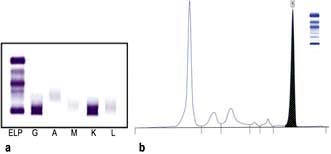

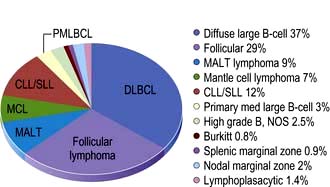

B-cell lymphomas (Fig. 9.21)

Follicular lymphoma

This is the second commonest non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (comprising approximately 20% of the lymphomas in the world).

Figure 9.21 Relative frequencies of B-cell lymphoma subtypes in adults.

(Reproduced with permission from the WHO. Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL et al. WHO Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues, 4th edn. Geneva: WHO; 2008: Fig 8.06, p. 164.)

Clinical presentation and course

Follicular lymphoma occurs in middle to late life, being rare in childhood. The majority of patients will present with painless lymphadenopathy at more than one site, although a small proportion will be ill, some with ‘B’ symptoms. In the latter, there should be suspicion that the diagnostic biopsy was not representative. This may be the case when the presenting symptom relates to an abdominal mass, but a peripheral node is biopsied. Percutaneous needle biopsy of the abdominal mass may reveal transformation to diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, with potentially different management. Bone marrow infiltration is common in certain subtypes.

There have been dramatic improvements in the outcome of therapy since the introduction of antibody therapy (rituximab), targeting the CD20 antigen expressed on almost all B-cell lymphomas, leading to the development of chemoimmunotherapy, but to date, however, the proportion of patients cured has been small. The illness has been shown to regress spontaneously in some cases which has led to an expectant policy of treatment for many patients. The clinical course following initiation of treatment to date has been that of a remitting recurring disease, often with several biopsy-proven episodes of lymphadenopathy which are, albeit usually transiently, responsive to therapy. Transformation to diffuse large B-cell lymphoma occurs in up to 25% of patients over 15 years and usually heralds a grave prognosis, although this may be improving. Death occurs because of resistant disease, transformed or not, the complications of therapy, or unrelated causes. The median survival now exceeds 10 years. Prognostic factor are shown in Box 9.9.

Management

General management

Lymph node biopsy accompanied by appropriate further investigation should precede any treatment decision. The ‘well’ patient variously defined, but certainly without symptoms, organ impairment, ‘bulky disease’ or evidence of rapid progression or transformation should, after a careful explanation of the rationale, be managed expectantly. This approach is followed by progression mandating therapy in about two and a half years for half the patients, with 20% having had some spontaneous regression and 15% having had no treatment, more than 10 years since diagnosis. A large trial comparing expectant management with immunotherapy with rituximab, however, shows a very considerable delay to having the first treatment in the rituximab group. The implications of this are unclear. Indications for treatment of low-grade non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma are shown in Box 9.10.

![]() Box 9.10

Box 9.10

Indications for treatment of low-grade NHL at presentation or progression

Initial treatment: early disease

Stage I (possibly stage II): This is treated with involved field megavoltage irradiation, which almost always induces complete remission, with 50% being disease-free after 10–15 years. There are no randomized trials to show this is better in terms of overall survival than expectant management (i.e. observe and treat if progression occurs). Functional imaging, i.e. PET scanning, may identify patients who are in ‘surgical CR’ post-biopsy for whom no therapy is indicated.

Initial treatment: advanced disease (stages II–IV)

Chemoimmunotherapy incorporating rituximab is the treatment of choice having been shown in randomized trials to be superior to chemotherapy alone, in terms of disease-free, progression-free and overall survival. ‘CHOP-R’ (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine and prednisolone + rituximab) and the less intensive ‘R-CVP’ (rituximab + cyclophosphamide, vincristine and prednisolone) are both widely used and R-Bendamustine is gaining popularity. Over the next few years, it will become clear which chemotherapy is the best for which group of patients. It has been shown that continuing rituximab ‘maintenance’ for 2 years has a dramatic effect on progression-free survival, although as yet not on overall survival. If rituximab maintenance is not given, patients in complete or (‘good’) partial remission are managed expectantly, until progression occurs. This is challenged by data showing that consolidation with radio-immunotherapy (90yttrium anti-CD20) also prolongs disease-free survival. Trials are in progress to determine whether consolidation with myeloablative chemotherapy, with or without rituximab maintenance, improves outcome further.

Two studies have shown the efficacy of prolonged rituximab alone; the role of intensive therapy in standard practice is being questioned.

Second therapy and beyond

Patients are managed expectantly in the first instance, provided full re-evaluation, including repeat biopsy, reveals no evidence of transformation. A number of options are available, including re-induction of remission with combined chemoimmunotherapy, followed by rituximab maintenance in those not ‘rituximab resistant’. Myeloablative consolidation chemotherapy is used in younger patients, particularly those in whom the first remission was short. Reduced-intensity conditioning allogeneic haematopoetic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) has yielded very impressive results in selected patients that may be curative despite the toxicity of the treatment.

The biggest challenges lie in patients with ‘resistant disease’ and in the treatment of ‘transformation’. A number of experimental agents with new antibodies, immunomodulatory agents and drugs targeted to specific pathways are showing promise.

Summary

There has been a dramatic improvement in the overall survival pattern of follicular lymphoma as the result of introducing anti-CD20 (rituximab) in the treatment of advanced disease. The median survival has been extended, well beyond 10 years in several series, albeit possibly selected patients. Improvements in disease-free survival, both after initial and second-line therapy, are encouraging. It is reasonable to anticipate that further improvement will be seen with the selective use of allogeneic stem cell transplantation and the new targeted therapies under investigation.

FURTHER READING

Relander T, Johnson NA, Farinha P et al. Prognostic factors in follicular lymphoma. J Clin Oncol 2010; 28(17):2902–2913.

Salles G, Seymour JF, Offner F et al. Rituximab maintenance for 2 years in patients with high tumour burden follicular lymphoma responding to rituximab plus chemotherapy (PRIMA): a phase 3 randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2011; 377:42–51.

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL)

Introduction

This is the commonest lymphoma worldwide in the adult population (increasing in incidence with age) and the second commonest in childhood, accounting for approximately 30% of all cases. There is a slight male preponderance.

Clinical presentation

The majority of patients present with painless lymphadenopathy, clinically at one or several sites. Intra-abdominal disease presents with bowel symptoms due to compression or infiltration of the gastrointestinal tract. In a small proportion there is a primary mediastinal presentation, most often in men, with symptoms and signs akin to those of Hodgkin’s lymphoma. There may be ‘B symptoms’, which should not be confused with symptoms related to the site of involvement. Investigation will lead to the demonstration of either locally or systematically advanced disease in the majority of cases. The illness is itself rapidly progressive, without intervention, death occurring within months rather than years. Approximately 30% present at an extranodal site as opposed to having nodal disease with extranodal spread.

Initial treatment

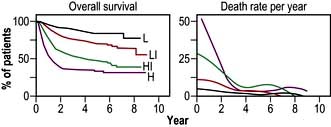

Treatment should be initiated immediately after the diagnosis is confirmed and in younger patients without co-morbidity there is a high expectation of cure. Treatment is assigned on the basis of the International Prognostic Index (Box 9.9, Fig. 9.22).

Figure 9.22 A predictive model for aggressive non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Survival among the 1274 younger patients (≤60 years) according to risk group defined by the age-adjusted international index. L, low risk; LI, low–intermediate risk; HI, high–intermediate risk; H, high risk.

(Reproduced with permission from: The International Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma Prognostic Factors Project. A predictive model for aggressive non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. New England Journal of Medicine 1993; 329(14):987–994.)

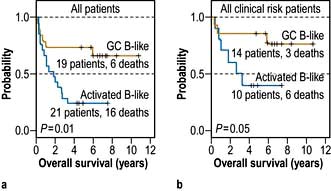

Although this was constructed in the pre-rituximab era, it remains broadly applicable. Further refinement using gene expression profiling has identified at least two distinct subtypes of DLBCL (Fig. 9.23). Allopurinol is given routinely and also in some cases with different prognoses – germinal centre cell (GC) and activated B-cell (AB). A high proliferative index, aggressive prophylaxis against tumour lysis is indicated.

Figure 9.23 Kaplan–Meier plot of overall survival of DLBCL patients grouped on the basis of gene expression profiling.

(Reproduced with permission from Alizadeh AA. Distinct types of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma identified by gene expression profiling. Nature 2000; 403(6769):503–511.)

Low-risk (IPI score 0–1) with anatomically localized disease

At present, ‘R-CHOP’ followed by involved field irradiation, or ‘more R-CHOP’, are both used. Interim PET scanning may be used to inform individualization of therapy.

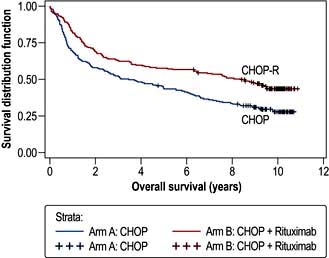

Two studies conducted in France suggest that the prognosis is better with chemotherapy alone provided ‘enough’ is given, with more than 80% of younger patients being alive 10 years after therapy. A trial comparing ‘R-chemo’ with ‘chemo’ in all patients with low-risk disease showed a marked advantage for those receiving chemoimmunotherapy. Further studies are awaited (Fig. 9.24).

Figure 9.24 Overall survival in patients treated with CHOP and R-CHOP. Median overall survival (OS) was 3.5 years (95% CI: 2.2–5.5) in the CHOP arm and 8.4 years (95% CI: 5.4–not reached) in the R-CHOP arm (p<0.0001). DLBCL, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma.

(Reproduced with permission from Coiffier B, Thieblemont C, Van Den Neste et al. Long-term outcome of patients in the LNH-98.5 trial, the first randomized study comparing rituximab-CHOP to standard CHOP chemotherapy in DLBCL patients: a study by the Groupe d’Etudes des Lymphomes de l’Adulte. Blood 2010; 116(12):2040–2045.)

Intermediate and poor-risk (IPI score 2+)

The age of the patient and co-morbidity are critical for both the selection of treatment and the prognosis. Recognition of this fact has led to the use of an age-adjusted prognostic index for patients over the age of 60. Chemoimmunotherapy was established to be superior to chemotherapy alone for older patients in this category. ‘R-CHOP’, to a total of 6 or 8 cycles, has become standard care for the large majority of patients of all ages with DLBCL.

Many trials of increasing intensity of therapy for selected patients have yet to yield convincing results. However, there is an increasing consensus that the small group of patients having DLBCL with ‘Burkitt-like features’ should be treated as for Burkitt’s lymphoma. The ability to distinguish between the molecularly distinct, ‘germinal centre’ and ‘activated B cell’, DLBCL with immunohistochemistry, has made it possible to explore different therapeutic approaches in the two groups, with appropriate targeted agents

Involvement of the central nervous system, most often meningeal, is an uncommon but devastating complication, confirming a very poor prognosis overall. Patients with a high IPI score and particularly those with specific extranodal sites of involvement (testis, paranasal sinuses, bone marrow) and those who are HIV-positive should receive intrathecal methotrexate with each cycle of therapy. The management of overt leptomeningeal or parenchymal involvement, often in the context of generalized lymphoma, is difficult and usually unsuccessful in the long term. Most strategies involve high doses of systemic methotrexate and cytosine arabinoside, both of which cross the blood–brain barrier. Cranial or craniospinal irradiation is also used.

Second (and subsequent) therapy

Although there may be responsiveness initially to alternative chemotherapy, after failure of initial therapy or subsequent progression, the prognosis is very poor. Patients entering a partial remission do better than those who recur after entering an initial complete remission.

The major issues to be addressed are whether treatment is to be undertaken with palliative or curative intent and if the latter, the expectations of success. The palliative approach involves both chemotherapy and irradiation. The curative approach involves complete re-evaluation followed by second-line chemotherapy, with a proven response rate of approximately 50%. If at least a further partial remission is achieved, in the younger, fitter patient, peripheral blood stem cell harvest is undertaken, followed, if successful, by an autograft. Overwhelmingly, the best results are achieved in those entering an unequivocal second complete remission. Even so, the proportion of patients in a prolonged second remission does not exceed 25%.

Prognosis

The outlook for patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma has improved by at least 15% in terms of cure, with the incorporation of rituximab into the initial therapy, the expectation of cure now being between 40% and 80% depending on the presenting features. The challenge of progressive disease following initial treatment is great, with overall less than 20% of patients alive long term.

Burkitt’s lymphoma

Introduction

This is the most rapidly proliferating lymphoma with a doubling time approaching 100% and a very rapid evolution. The commonest childhood malignancy worldwide, it has a male : female preponderance of approximately 3 : 1 and occurs in all ages. There are three types:

The commonest presenting feature in the endemic type is a rapidly growing jaw tumour in a young child (Fig. 9.25). Otherwise, the next commonest is an abdominal mass often associated with bone marrow involvement. Other common sites are the central nervous system, the kidney and the testis. Investigation is along conventional lines for lymphoma, at least in the Western world, but must be conducted as a matter of urgency. A different staging classification is applied to children.

Management

Burkitt’s lymphoma should be treated with curative intent whenever feasible, regardless of HIV status. Investigation having been completed, it is essential that the patient is haemodynamically and metabolically stable prior to the initiation of specific therapy. Particular attention must be paid to the risk of the tumour lysis syndrome. Whenever possible, rasburicase prophylaxis should be given. If this is not available, other standard measures based on fluids and allopurinol to minimize the risk of tumour lysis syndrome should be pursued. Very frequent monitoring of electrolyte balance is essential for at least 72 hours after treatment is commenced, with particular attention to potassium and phosphate levels.

Standard treatment comprises if possible, intensive, cyclical combination chemotherapy, including cyclophosphamide, methotrexate and cytosine arabinoside in high doses. Rituximab is now included, although the evidence base for this is minimal. The details and number of cycles administered will be determined by the perceived level of ‘risk’. Prophylactic central nervous system therapy is essential, intrathecal methotrexate or cytosine arabinoside often being given in addition to high-dose systemic administration. The chances of cure are very high for ‘low-risk’ patients and exceed 50% for ‘poor-risk’ patients as well, provided all treatment can be administered.

Failure to achieve complete remission is a very poor prognostic factor as is recurrence, which does so within the first year after completion of initial therapy if it is to happen. Although there may be further chemo-responsiveness, it is rare for second-line therapy to be more than transiently beneficial, regardless of whether it is followed by consolidation, with either myeloablative chemotherapy or allogeneic haematopoeitic stem cell transplantation.

Mantle cell lymphoma

This is one of the less common B-cell lymphomas, presenting usually in later life, with a male to female preponderance of 3 : 1. The commonest presentation is with painless lymphadenopathy, often generalized. There may be nonspecific symptoms of tiredness, or those related to the gastrointestinal tract. ‘B’ symptoms occur in <50%. Examination and standard investigation usually confirm generalized lymphadenopathy with or without hepatosplenomegaly (Fig. 9.26). Patients with bowel symptoms frequently have multiple lesions found on endoscopy. The bone marrow is usually involved and there may well be lymphoma cells in the peripheral blood.

Figure 9.26 CT of the abdomen of a patient with mantle cell lymphoma showing significant splenomegaly.

Treatment

In the majority of patients, therapy is started after investigation has been completed. It is usual for there to be regression of disease with chemotherapy, although it is not often that complete remission is achieved. A prognostic index is used to help determine whether more or less ‘aggressive’ treatment is best employed. In reality, the major determining factors are the age of the patient and the presence or absence of co-morbidities. The outcome is likely to be best when ‘more’ treatment is given. Hence, younger, fitter patients are now treated with relatively intensive chemoimmunotherapy, incorporating rituximab, followed by, depending on its efficacy, myeloablative chemotherapy, with autologous stem cell rescue. Older, less fit patients are treated with less intensive therapy. In general, the strategy is to stop treatment after the planned initial course of treatment, provided the patient is well and at least a partial remission has been achieved. Almost inevitable progression for both older and younger patients occurs; palliation being the expectation for most. Experimental approaches include reduced intensity allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation and novel drugs targeting both the NFκB and mTOR pathways.

Summary

Mantle cell lymphoma is a lymphoma with a natural history untreated which lies between that of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and follicular lymphoma. The prognosis has improved in recent years with the introduction of treatment strategies which have prolonged the period of remission without curing the patient and with the discovery of new ‘effective’ agents, making the overall median survival nearer 5 years.

Lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma

This is an uncommon, B-cell malignancy, which when associated with an IgM paraprotein and bone marrow infiltration is known as Waldenström’s macroglobulinaemia. It usually occurs in later life, the incidence being approximately the same in men and women. It may be preceded by a pre-lymphomatous phase, in which a small, monoclonal IgM band is present, often an incidental finding, for many years. The presentation is with lymphadenopathy or alternatively with symptoms of anaemia or hyperviscosity due to the paraprotein (e.g. headaches, visual disturbance). Examination and investigation usually reveal little beyond minimal adenopathy and commonly splenomegaly.

Management

Following completion of investigation, the critical decision is whether to initiate specific therapy or not. A prognostic score is assigned, the critical decision being whether to initiate specific therapy or not. In an emergency, with severe symptoms of hyperviscosity, it is most appropriate to lower the paraprotein by plasmapheresis. In some circumstances, particularly in the otherwise less fit, it may be best to use maintenance pheresis and blood transfusion as the primary therapy. ‘Responses’ occur in about 50% of cases, with a fall in the paraprotein to 50% of the baseline level with single agent therapy and higher with combination chemotherapy and rituximab. The general strategy is to treat when it is clinically indicated and to stop after a conventional course of treatment. Treatment, either repeating the initial therapy or changing, is re-instated only when progression is clearly documented, most often by fall in the haemoglobin or significant rise in the M-band and the illness is a threat to quality and quantity of life. In the very small proportion of younger patients for whom complete remission is achieved, consolidation with a bone marrow transplant is used. Similarly, in the same group of patients who have recurrent disease, which is again responsive, allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation is also used.

Primary extranodal lymphoma

Lymphoma may arise anywhere in the body where there is lymphoid tissue and therefore the clinical presentation is that of a lesion or mass at the relevant site. In practice the majority occur in the central nervous system, the stomach, or the skin.

Primary central nervous system lymphoma

This diffuse large B-cell lymphoma occurs in both the immunocompetent (predominantly the elderly) and the immunosuppressed, in the context of post-solid organ transplant or HIV infection. It presents with symptoms relating to single or multiple parenchymal mass lesions. The diagnosis needs to be made on the basis of a biopsy, particularly in the immunocompromised, in whom an infectious aetiology of the symptoms is possible, e.g. toxoplasmosis. MRI scan is the first choice investigation; cerebrospinal fluid is usually normal. Further investigation is necessary to exclude the cerebral lesion being a manifestation of generalized disease.

Treatment

In some patients in the post-transplant setting, reduction of immune suppression may be beneficial. Chemotherapy alone, with high-dose methotrexate and cytosine arabinoside, is used. Possibly, the best ‘disease-free’ results have been obtained by the use of chemotherapy and irradiation but toxicity is greater, with a risk of irreversible loss of cerebral function. The overall results are disappointing with only a small proportion of patients alive long-term without disability. The situation in the HIV-positive patient with cerebral lymphoma (fortunately a declining problem) is much worse and palliative irradiation is the best option.

Primary gastric lymphoma

This B-cell lymphoma, either extranodal marginal zone lymphoma of mucosa-associated tissue (MALT), or diffuse large B-cell lymphoma arising on a background of MALT lymphoma, is closely related to Helicobacter infection. It presents with symptoms of gastric ulceration or a mass, indigestion or bleeding and the diagnosis is made by endoscopic biopsy to include both the confirmation of lymphoma and H. pylori status. This is followed by investigation as for nodal lymphoma, which reveals local nodal involvement in a proportion of patients and distant spread in only a small number. Treatment is entirely dependent on whether or not there is any evidence of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. If only ‘low-grade’ gastric ‘MALT’ lymphoma is present, Helicobacter eradication therapy is the treatment of choice (p. 249). This almost invariably alleviates the symptoms. Re-evaluation after 3 months with endoscopy, repeat biopsy and in some circumstances, endoscopic ultrasound is carried out. In general, a conservative approach is followed, as responses may take many months to achieve and rapid progression is very unlikely. Regular endoscopy 6-monthly should be continued for at least 2 years. Failure is not common and if it occurs, it is rarely rapid. If it occurs, the biopsy should be repeated. If the histology is unchanged after further Helicobacter eradication therapy (if necessary) either irradiation to the gastric bed or chemoimmunotherapy is likely to be effective or possibly curative. Overall, the prognosis is very good, the very large proportion of patients being alive 10 years after diagnosis.

Any evidence of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma is an indication for chemoimmunotherapy. Helicobacter eradication therapy should also be given, but should not be considered definitive treatment. The potential risk of gastric perforation or haemorrhage because of therapy is not a contraindication to treatment. Surgery is rarely needed, but irradiation is used for persistent disease. The prognosis is approximately the same as for nodal DLBCL of equivalent extent.

Primary cutaneous lymphoma (T or B cell)

Lymphomas of both B- or T-cell type may arise singly and multiply in the skin and pursue a very long natural history even though they may give rise to considerable discomfort.

Mycosis fungoides, Sézary syndrome

This is the commonest cutaneous lymphoma, predominantly arising in and confined to the skin, although later in the disease spreading to other organs. It has a long natural history, being sometimes preceded by a scaly ‘pre-mycotic phase’. This T-cell lymphoma presents with multiple erythematous lesions, plaques and tumours, which when associated with spread to the blood, become the Sézary syndrome. Generalized erythema may occur (erythroderma). The likelihood over time of disease extending beyond the skin is highest in patients with tumours.

Treatment is palliative and there is little indication that the disease is ever eradicated. Many treatments result in regression of disease. Antibiotics are used for infection. Phototherapy (PUVA), topical steroids and topical chemotherapy all lead to response. Radiation is effective and total skin electron beam therapy particularly so, although attention must be given to potential side-effects including erythroderma. Systemic chemotherapy, either at conventional or high doses, has been disappointing. Newer approaches include anti-T-cell antibodies and histone deacetylase inhibitors The median survival is approximately 10 years, there being close correlation with the extent of disease at presentation. Interaction between oncologist and dermatologist is essential.

Cutaneous B-cell lymphoma

The two major subtypes are extranodal marginal zone and follicle centre in origin. Both usually present with either single or clustered cutaneous lesions, biopsy of which confirms the diagnosis. All conventional staging investigations are negative. Treatment is either expectant, surgical excision or irradiation, which may be used repeatedly over time. Antibiotics are used for marginal zone lymphoma if there is evidence of Borrelia burgdorferi infection. Only if there are lesions at multiple sites should systemic chemotherapy be used. The long-term prognosis is excellent.

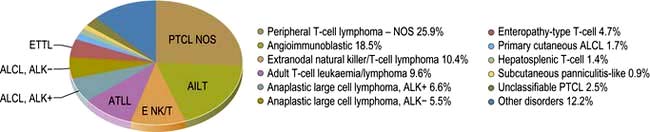

T and natural killer (NK) cell lymphomas (Fig. 9.27)

Introduction

These are much less common than their B-cell counterparts, although they are relatively more frequent in the East than the West. The commonest presentations are nodal or cutaneous (p. 1226) and specific subtypes involve the liver and subcutaneous tissue. Peripheral T-cell lymphomas with nodal presentation have a poor prognosis. They are treated as for DLBCL without rituximab.

Figure 9.27 Relative frequencies of T-cell lymphoma subtypes in adults. NOS, not otherwise specified.

(Reproduced with permission from WHO. Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL et al. WHO Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues, 4th edn. Geneva: WHO; 2008: Fig 8.07.)

The two ‘commonest subtypes’ of ‘nodal’ T-cell lymphoma are peripheral T-cell lymphoma, ‘not otherwise specified’ (NOS) and angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma, which together account for about 50% of T-cell lymphomas. Both occur in the middle-aged to elderly population, the primary presentation being lymphadenopathy. In contrast to the B-cell lymphomas, ‘B symptoms’ are common. Patients with angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma also present with features akin to inflammatory disease, with fevers, rashes and electrolyte abnormalities, which in the first instance may be rapidly responsive to corticosteroids or low doses of alkylating agents.

Management

Following standard investigation, which usually reveals widespread disease, patients are treated with cyclical combination chemotherapy as used for diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. CD20 is not expressed on T cells so rituximab is not used and, as yet, there is no equivalent drug for T-cell lymphoma. Resolution of symptoms almost invariably occurs, although they may recur between cycles. Overall, the outcome of treatment is worse than for DLBCL, in terms of quality of response, duration of response and overall survival. Second-line therapy is rarely satisfactory, although a small proportion of patients may benefit from myeloablative therapy to consolidate a second response.