Health Problems of Early Childhood

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Wong/ncic/

Collection of Specimens, Ch. 27

Compliance, Ch. 27

Controlling Elevated Temperatures, Ch. 27

Growth Failure (Failure to Thrive), Ch. 13

Immunizations, Ch. 12

Infection Control, Ch. 27

Pain Assessment; Pain Management, Ch. 7

Pertussis (Whooping Cough), Ch. 32

Poisoning, Ch. 14

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder, Ch. 18

Rape, Ch. 20

Seizure Disorders, Ch. 37

Skin Lesions, Ch. 18

Stool Specimens, Ch. 27

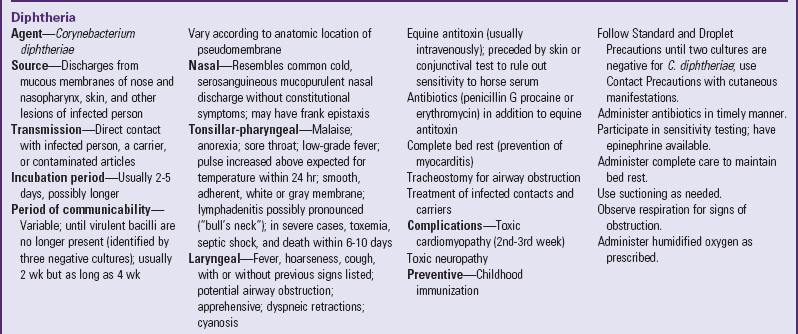

Infectious Disorders

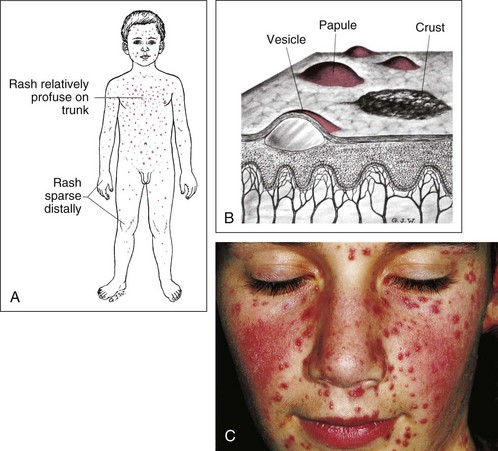

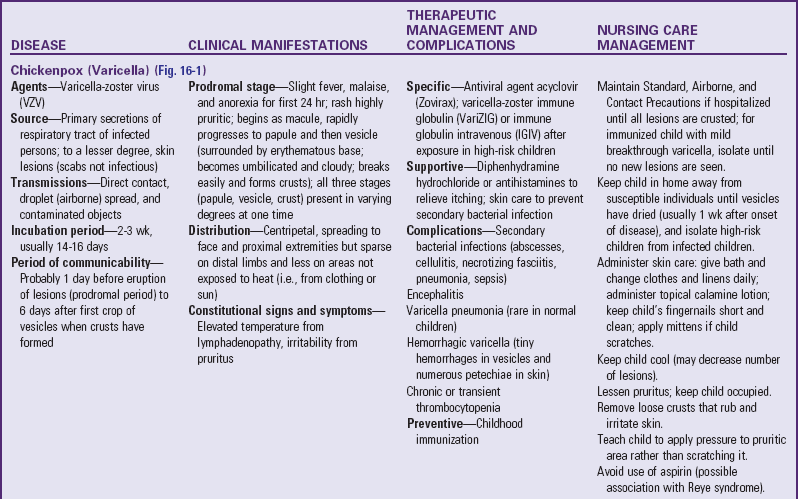

![]() The incidence of childhood communicable diseases has declined significantly since the advent of immunizations. The use of antibiotics and antitoxins has further reduced serious complications resulting from such infections. However, infectious diseases do occur, and nurses must be familiar with the infectious agent to recognize the disease and to institute appropriate preventive and supportive interventions (Table 16-1). (See also Chapter 18 for a discussion of nursing care for dermatologic conditions.)

The incidence of childhood communicable diseases has declined significantly since the advent of immunizations. The use of antibiotics and antitoxins has further reduced serious complications resulting from such infections. However, infectious diseases do occur, and nurses must be familiar with the infectious agent to recognize the disease and to institute appropriate preventive and supportive interventions (Table 16-1). (See also Chapter 18 for a discussion of nursing care for dermatologic conditions.)

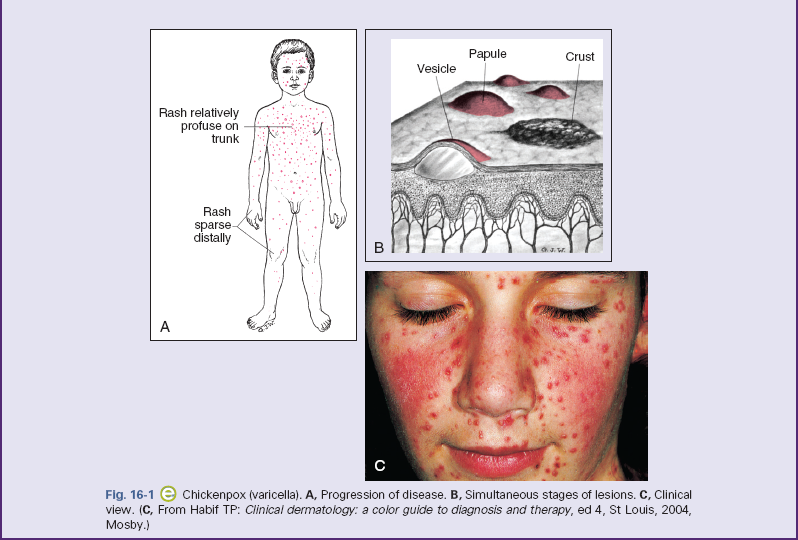

Fig. 16-1 ![]() Chickenpox (varicella). A, Progression of disease. B, Simultaneous stages of lesions. C, Clinical view.

Chickenpox (varicella). A, Progression of disease. B, Simultaneous stages of lesions. C, Clinical view.![]() Animation—Chickenpox (Varicella Zoster) (C, From Habif TP: Clinical dermatology: a color guide to diagnosis and therapy, ed 4, St Louis, 2004, Mosby.)

Animation—Chickenpox (Varicella Zoster) (C, From Habif TP: Clinical dermatology: a color guide to diagnosis and therapy, ed 4, St Louis, 2004, Mosby.)

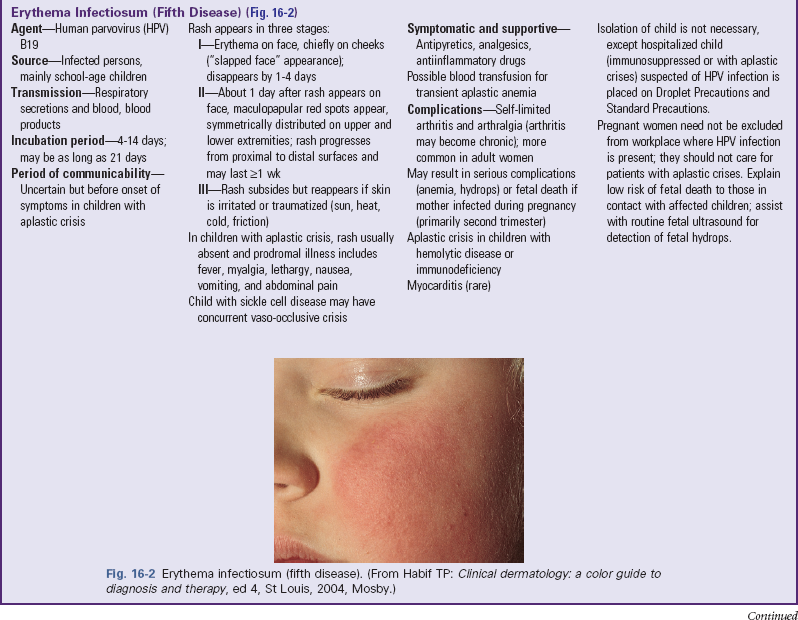

Fig. 16-2 Erythema infectiosum (fifth disease). (From Habif TP: Clinical dermatology: a color guide to diagnosis and therapy, ed 4, St Louis, 2004, Mosby.)

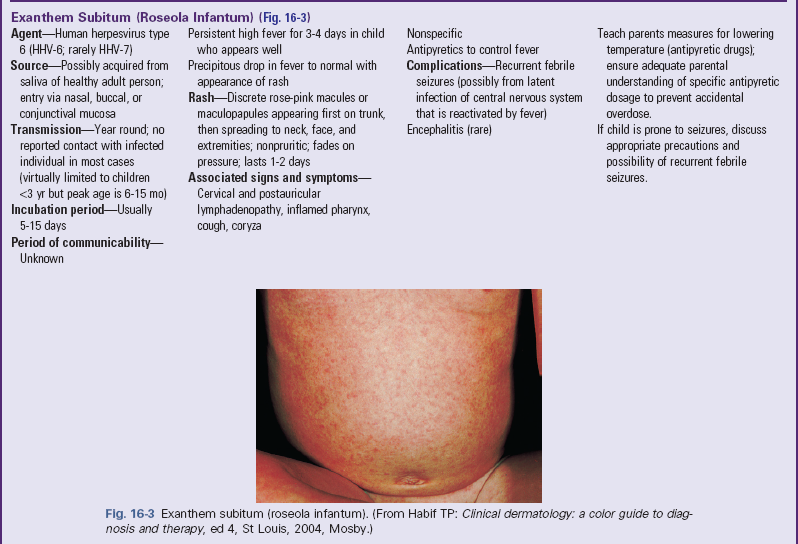

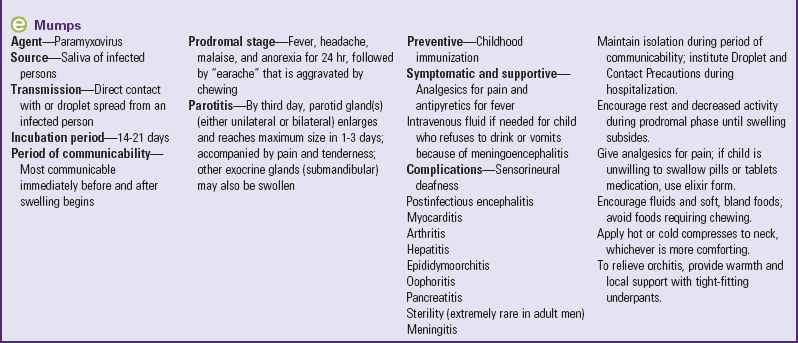

Fig. 16-3 Exanthem subitum (roseola infantum).![]() Animation—Mumps (From Habif TP: Clinical dermatology: a color guide to diagnosis and therapy, ed 4, St Louis, 2004, Mosby.)

Animation—Mumps (From Habif TP: Clinical dermatology: a color guide to diagnosis and therapy, ed 4, St Louis, 2004, Mosby.)

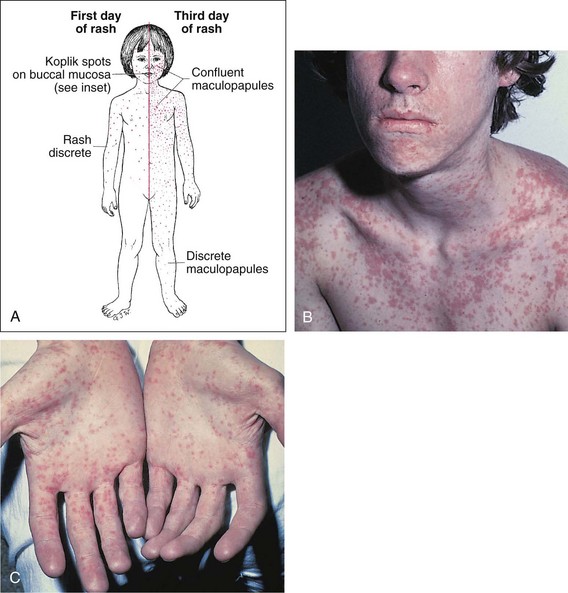

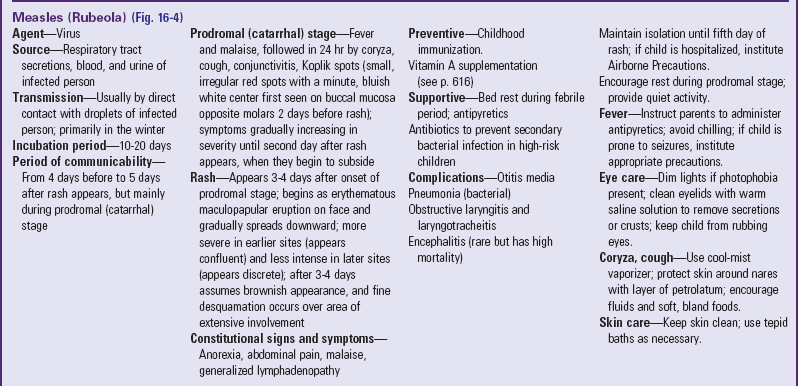

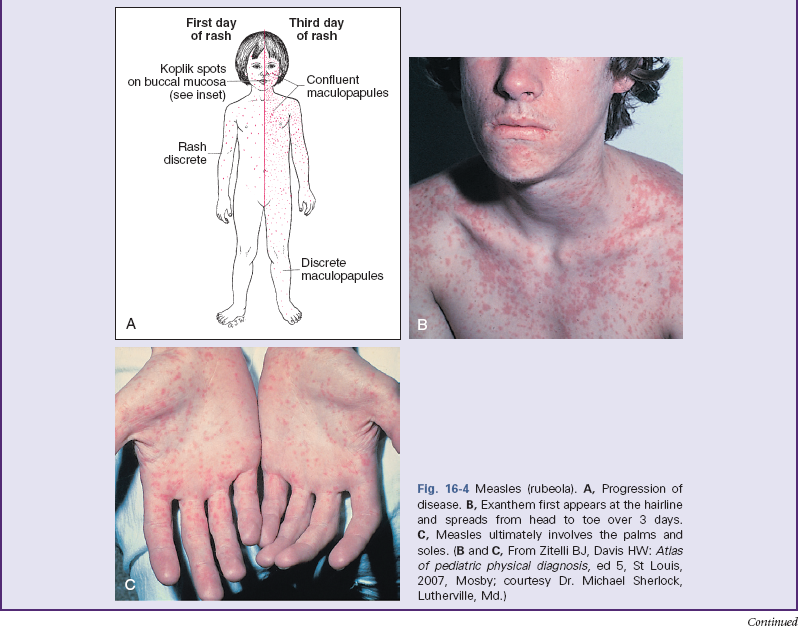

Fig. 16-4 Measles (rubeola). A, Progression of disease. B, Exanthem first appears at the hairline and spreads from head to toe over 3 days. C, Measles ultimately involves the palms and soles. (B and C, From Zitelli BJ, Davis HW: Atlas of pediatric physical diagnosis, ed 5, St Louis, 2007, Mosby; courtesy Dr. Michael Sherlock, Lutherville, Md.)

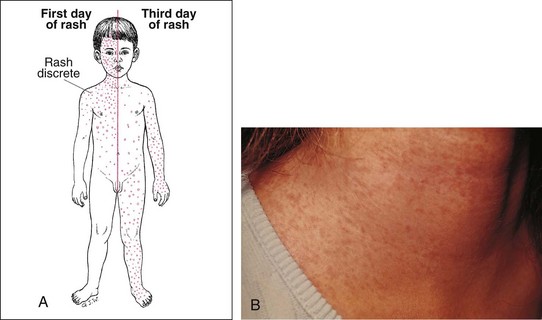

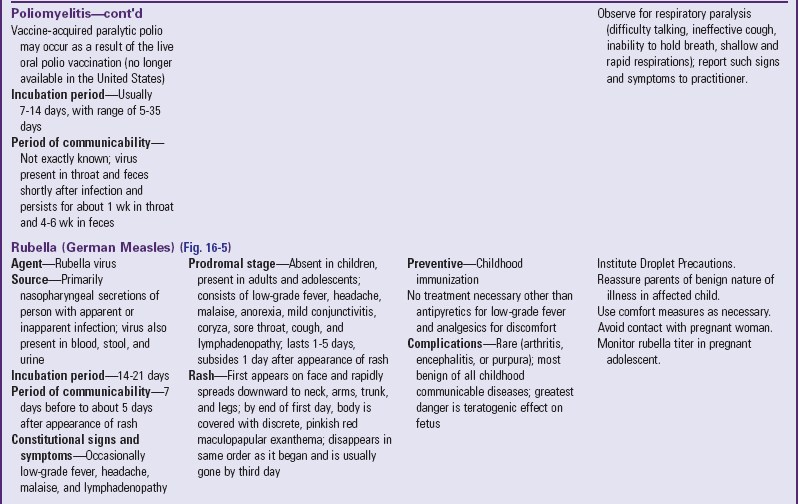

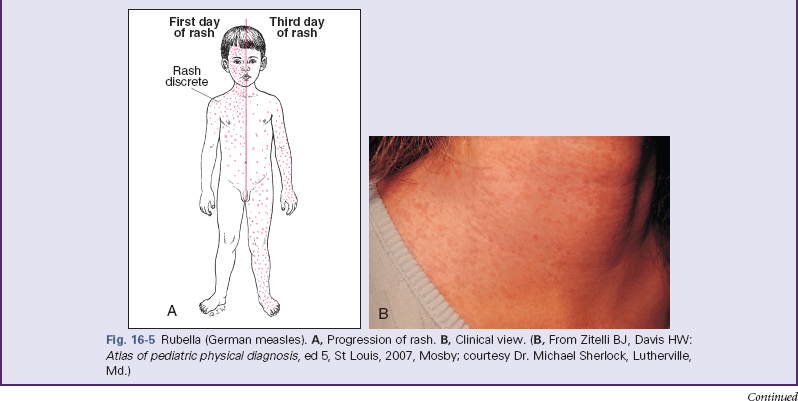

Fig. 16-5 Rubella (German measles). A, Progression of rash. B, Clinical view. (B, From Zitelli BJ, Davis HW: Atlas of pediatric physical diagnosis, ed 5, St Louis, 2007, Mosby; courtesy Dr. Michael Sherlock, Lutherville, Md.)

![]() Case Study—Chickenpox (Varicella)

Case Study—Chickenpox (Varicella)

Nursing Care Management

Table 16-1 describes the more common communicable diseases of childhood, their therapeutic management, and specific nursing care. The following is a general discussion of nursing care management for communicable diseases.

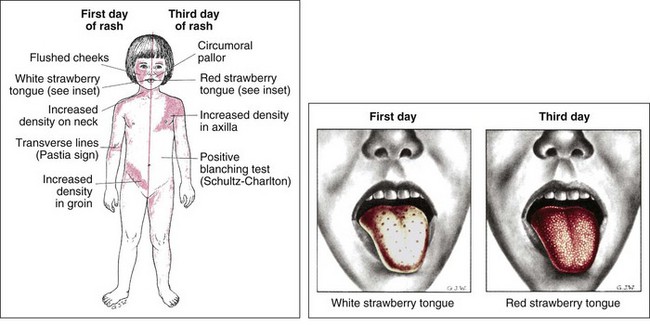

Identification of the infectious agent is of primary importance to prevent exposure to susceptible individuals. Nurses in ambulatory care settings, child care centers, and schools are often the first persons to see signs of a communicable disease, such as a rash or sore throat. The nurse must operate under a high index of suspicion for common childhood diseases to identify potentially infectious cases and to recognize diseases that require medical intervention. An example is the common complaint of sore throat. Although most often a symptom of a minor viral infection, it can signal diphtheria or a streptococcal infection, such as scarlet fever. Each of these bacterial conditions requires appropriate medical treatment to prevent serious complications.

When the nurse suspects a communicable disease, it is important to assess:

• Recent exposure to a known case

• Prodromal symptoms (symptoms that occur between early manifestations of the disease and its overt clinical syndrome) or evidence of constitutional symptoms, such as a fever or rash (see Table 16-1)

Immunizations are available for many diseases, and infection usually confers lifelong immunity; therefore the possibility of many infectious agents can be eliminated based on these two criteria.

Prevent Spread: Prevention consists of two components: prevention of the disease and control of its spread to others. Primary prevention rests almost exclusively on immunization. (Chapter 12 discusses the nurse’s role in immunization of children.)

Control measures to prevent spread of disease should include techniques to reduce risk of cross-transmission of infectious organisms between patients and to protect health care workers from organisms harbored by patients. If the child is hospitalized, follow the facility’s policies for infection control. (See Chapter 27.) The most important procedure is hand washing. Persons directly caring for the child or handling contaminated articles must wash their hands and practice effective Standard Precautions in care of their patients.

Instruct the child to practice good hand-washing technique after toileting and before eating. For those diseases spread by droplets, the nurse instructs parents in measures to reduce airborne transmission. The child who is old enough should use a tissue to cover the face during coughing or sneezing; otherwise, the parent should cover the child’s mouth with a tissue and then discard it. Stress the usual hygiene measures of not sharing eating and drinking utensils to the family.

Prevent Complications: Although most children recover without difficulty, certain groups are at risk for serious, even fatal, complications from communicable diseases, especially the viral diseases chickenpox and erythema infectiosum (EI) (fifth disease) caused by human parvovirus (HPV) B19.

Children with immunodeficiency—those receiving steroid or other immunosuppressive therapy, those with a generalized malignancy such as leukemia or lymphoma, or those with an immunologic disorder—are at risk for viremia from replication of the varicella-zoster virus (VZV)* in the blood. VZV is so named because it causes two distinct diseases: varicella (chickenpox) and zoster (herpes zoster or shingles). Varicella occurs primarily in children younger than 15 years of age. However, it leaves the threat of herpes zoster, an intensely painful varicella that is localized to a single dermatome (body area innervated by a particular segment of the spinal cord). In children the dermatomes most likely affected by herpes zoster are the cervical and sacral dermatomes (Leung, Robson, and Leong, 2006). Immunocompromised patients and healthy infants younger than 1 year of age (who also have reduced immunity) are at a higher risk for reactivation of VZV causing herpes zoster, probably as a result of a deficiency in cellular immunity (American Academy of Pediatrics, 2009; Galea, Sweet, Beninger, et al, 2008). Complications of herpes zoster virus in children include secondary bacterial infection, depigmentation, and scarring. Postherpetic neuralgia in children is uncommon (Leung, Robson, and Leong, 2006).

![]() The use of varicella-zoster immune globulin (VariZIG) or immune globulin intravenous (IGIV) is recommended for children who are immunocompromised, who have no previous history of varicella, and who are likely to contract the disease and have complications as a result (American Academy of Pediatrics, 2009). The antiviral agent acyclovir (Zovirax) may be used to treat varicella infections in susceptible immunocompromised persons. It is effective in decreasing the number of lesions; shortening the duration of fever; and decreasing itching, lethargy, and anorexia. Consider oral acyclovir for immunocompromised children without a history of varicella disease, newborns whose mother had varicella within 5 days before delivery or within 48 hours after delivery, and hospitalized preterm infants with significant varicella exposure (American Academy of Pediatrics, 2009).

The use of varicella-zoster immune globulin (VariZIG) or immune globulin intravenous (IGIV) is recommended for children who are immunocompromised, who have no previous history of varicella, and who are likely to contract the disease and have complications as a result (American Academy of Pediatrics, 2009). The antiviral agent acyclovir (Zovirax) may be used to treat varicella infections in susceptible immunocompromised persons. It is effective in decreasing the number of lesions; shortening the duration of fever; and decreasing itching, lethargy, and anorexia. Consider oral acyclovir for immunocompromised children without a history of varicella disease, newborns whose mother had varicella within 5 days before delivery or within 48 hours after delivery, and hospitalized preterm infants with significant varicella exposure (American Academy of Pediatrics, 2009).

![]() Case Study—Varicella in Spite of Vaccine

Case Study—Varicella in Spite of Vaccine

Children with hemolytic disease, such as sickle cell disease, are at risk for aplastic anemia from EI. HPV B19 infects and lyses red blood cell precursors, thus interrupting the production of red blood cells. Therefore the virus may precipitate a severe aplastic crisis in patients who need increased red blood cell production to maintain normal red blood cell volumes. Thrombocytopenia and neutropenia may also occur as a result of HPV B19 infection. The fetus has a relatively high rate of red blood cell production and an immature immune system; it may develop severe anemia and hydrops as a result of maternal HPV infection. Fetal death rates as a result of HPV B19 have been estimated to be between 2% and 6% (American Academy of Pediatrics, 2009).

In the past decade incidence of pertussis has increased, particularly in infants less than 6 months old and in children 10 to 14 years of age. Early clinical manifestations of pertussis in infants may include gagging, coughing, emesis, and apnea; the typical “whoop” associated with the disease is absent (Wood and McIntyre, 2008). In older children the disease may manifest as a common cold (see Table 16-1). There is now a recommendation that children ages 11 to 18 receive a booster pertussis vaccine (Tdap) to prevent the disease. (See Immunizations, Chapter 12.) Because pertussis is contagious, especially among close household members, identify pertussis early and initiate treatment for the child and those who have been exposed. Azithromycin (for infants <1 month) and erythromycin, clarithromycin, or azithromycin are administered to infants and children with pertussis (Wood and McIntyre, 2008).

Prevention of complications from diseases such as diphtheria, pertussis, and scarlet fever requires compliance with antibiotic therapy. With oral preparations, stress the need to complete the entire course of therapy. (See Compliance, Chapter 27.)

Evidence suggests that vitamin A supplementation reduces both morbidity and mortality in measles and that all children with severe measles should receive vitamin A supplements. A single oral dose of 200,000 international units for children at least 1 year old is recommended (use half that dose for children 6 to 12 months of age). The higher dose may be associated with vomiting and headache for a few hours. The dose should be repeated the next day and at 4 weeks for children with ophthalmologic evidence of vitamin A deficiency (American Academy of Pediatrics, 2009).

Provide Comfort: Many communicable diseases cause skin manifestations that are bothersome to the child. The chief discomfort from most rashes is itching, and measures such as cool baths (usually without soap) and lotions (e.g., calamine) are helpful.

To avoid overheating, which increases itching, children should wear lightweight, loose, nonirritating clothing and keep out of the sun. If the child persists in scratching, keep the nails short and smooth or use mittens and clothes with long sleeves or legs. For severe itching, antipruritic medication, such as diphenhydramine (Benadryl) or hydroxyzine (Atarax), may be required, especially when the child has trouble sleeping because of itching. Loratadine, cetirizine, and fexofenadine do not cause drowsiness and may be preferred for urticaria during the day.

An elevated temperature is common, and both antipyretic medicine (acetaminophen or ibuprofen) and environmental manipulation are implemented. (See Controlling Elevated Temperatures, Chapter 27.) The acetaminophen is effective in lowering the fever but does not significantly reduce the symptoms of itching, anorexia, abdominal pain, fussiness, or vomiting.

A sore throat, another frequent symptom, is managed with lozenges, saline rinses (if the child is old enough to cooperate), and analgesics. Because most children are anorectic during an illness, bland foods and increased liquids are usually preferred. During the early stages of the disease, children voluntarily curtail their activity, and although bed rest is beneficial, it should not be imposed unless specifically indicated. During periods of irritability, quiet activity (e.g., reading, music, television, video games, puzzles, coloring) helps distract children from the discomfort.

Support Child and Family: Most communicable diseases are benign, but may produce considerable concern and anxiety for parents. Often the occurrence of a disease such as chickenpox is the first time the child is acutely uncomfortable. Parents need assistance to cope with manifestations of the illness, such as intense itching. The family and child need reassurance that recovery is generally rapid. However, visible signs of the dermatosis may be present for some time after the child is well enough to resume usual activities.

Conjunctivitis

![]() Acute conjunctivitis (inflammation of the conjunctiva) occurs from a variety of causes that are typically age related. In newborns conjunctivitis can occur from infection during birth, most often from Chlamydia trachomatis (inclusion conjunctivitis) or Neisseria gonorrhoeae. These organisms, as well as herpes simplex virus (HSV), cause serious ocular damage. In infants recurrent conjunctivitis may be a sign of nasolacrimal (tear) duct obstruction. A chemical conjunctivitis may occur within 24 hours of instillation of neonatal ophthalmic prophylaxis; the clinical features include mild lid edema and a sterile, nonpurulent eye discharge (Fuloria and Kreiter, 2002). In children the usual causes of conjunctivitis are viral, bacterial, allergic, or related to a foreign body. Bacterial infection accounts for most instances of acute conjunctivitis in children. Diagnosis is made primarily from the clinical manifestations (Box 16-1), although cultures of purulent drainage may be needed to identify the specific cause.

Acute conjunctivitis (inflammation of the conjunctiva) occurs from a variety of causes that are typically age related. In newborns conjunctivitis can occur from infection during birth, most often from Chlamydia trachomatis (inclusion conjunctivitis) or Neisseria gonorrhoeae. These organisms, as well as herpes simplex virus (HSV), cause serious ocular damage. In infants recurrent conjunctivitis may be a sign of nasolacrimal (tear) duct obstruction. A chemical conjunctivitis may occur within 24 hours of instillation of neonatal ophthalmic prophylaxis; the clinical features include mild lid edema and a sterile, nonpurulent eye discharge (Fuloria and Kreiter, 2002). In children the usual causes of conjunctivitis are viral, bacterial, allergic, or related to a foreign body. Bacterial infection accounts for most instances of acute conjunctivitis in children. Diagnosis is made primarily from the clinical manifestations (Box 16-1), although cultures of purulent drainage may be needed to identify the specific cause.

![]() Case Study—Bacterial Conjunctivitis

Case Study—Bacterial Conjunctivitis

![]() Critical Thinking Exercise—Conjunctivitis

Critical Thinking Exercise—Conjunctivitis

Therapeutic Management

Treatment of conjunctivitis depends on the cause. Viral conjunctivitis is self-limiting, and treatment is limited to removal of the accumulated secretions. Bacterial conjunctivitis has traditionally been treated with topical antibacterial agents such as polymyxin and bacitracin (Polysporin), sodium sulfacetamide (Sulamyd), or trimethoprim and polymyxin (Polytrim). However, in one study of children with acute infective conjunctivitis treated by placebo versus topical chloramphenicol, there was little difference in cure rates; the authors concluded that most children will get better without antibiotic treatment (Rose, Harnden, Brueggemann, et al, 2005). Fluoroquinolones, approved for children ages 1 year and older, are viewed by ophthalmologists as the best ophthalmic antimicrobial agents available (Lichtenstein, Rinehart, and Levofloxacin Bacterial Conjunctivitis Study Group, 2003). Drops may be used during the day and an ointment at bedtime because the ointment preparation remains in the eye longer but blur the vision. Corticosteroids are avoided because they reduce ocular resistance to bacteria.

Nursing Care Management

Nursing care includes keeping the eye clean and properly administering ophthalmic medication. Remove accumulated secretions by wiping from the inner canthus downward and outward, away from the opposite eye. Warm, moist compresses, such as a clean washcloth wrung out with hot tap water, are helpful in removing the crusts. Compresses are not kept on the eye because an occlusive covering promotes bacterial growth. Instill medication immediately after the eyes have been cleaned and according to correct procedure. (See Chapter 27.)

Prevention of infection in other family members is an important consideration with bacterial conjunctivitis. Keep the child’s washcloth and towel separate from those used by others. Discard tissues used to clean the eye. Instruct the child to refrain from rubbing the eye and to use good hand-washing technique.

Stomatitis

Stomatitis is inflammation of the oral mucosa, which may include the buccal (cheek) and labial (lip) mucosa, tongue, gingiva, palate, and floor of the mouth. It may be infectious or noninfectious and may be caused by local or systemic factors. In children aphthous stomatitis and herpetic stomatitis are typically seen. Children with immunosuppression and those receiving chemotherapy or head and neck radiotherapy are at high risk for developing mucosal ulceration and herpetic stomatitis.

Aphthous stomatitis (aphthous ulcer, canker sore) is a benign but painful condition whose cause is unknown. Its onset is usually associated with mild traumatic injury (biting the cheek, hitting the mucosa with a toothbrush, or a mouth appliance rubbing on the mucosa), allergy, or emotional stress. The lesions are painful, small, whitish ulcerations surrounded by a red border. They are distinguished from other types of stomatitis by healthy adjacent tissues, absence of vesicles, and no systemic illness. The ulcers persist for 4 to 12 days and heal uneventfully.

Herpetic gingivostomatitis (HGS) is caused by HSV, most often type 1, and may occur as a primary infection or recur in a less severe form known as recurrent herpes labialis (commonly called cold sores or fever blisters). The primary infection usually begins with a fever; the pharynx becomes edematous and erythematous; and vesicles erupt on the mucosa, causing severe pain (Fig. 16-7). Cervical lymphadenitis often occurs, and the breath has a distinctly foul odor. In the recurrent form the vesicles appear on the lips, usually singly or in groups. The precipitating factors for the cold sores include emotional stress, trauma (often related to dental procedures), immunosuppression, or exposure to excessive sunlight. The disease can last 5 to 14 days, with varying degrees of severity.

Fig. 16-7 Primary gingivostomatitis. (From Thompson JM, McFarland GM, Hirsch JE, et al: Mosby’s clinical nursing, ed 5, St Louis, 2002, Mosby.)

Stomatitis may occur as a manifestation of hand-foot-and-mouth disease and herpangina; both manifest with scattered vesicles on the buccal mucosa and are commonly caused by the nonpolio enteroviruses (primarily coxsackieviruses). Children with either hand-foot-and-mouth or herpangina often have poor intake as a result of the mouth sores.

Therapeutic Management

Treatment for all types of stomatitis is aimed at relief of symptoms, primarily pain. Acetaminophen and ibuprofen are usually sufficient for mild cases, but with more severe HGS, stronger analgesics such as codeine may be needed. Topical anesthetics are helpful and include over-the-counter preparations such as Orabase, Anbesol, and Kank-A. Lidocaine (Xylocaine Viscous) can be prescribed for the child who can keep 1 tsp of the solution in the mouth for 2 to 3 minutes and then expectorate the drug. A mixture of equal parts of diphenhydramine elixir and Maalox (aluminum and magnesium hydroxide) provides mild analgesia, antiinflammatory properties, and a protective coating for the lesions. Sucralfate can also be used as a coating agent for oral mucous membranes. Specific treatment for children with severe cases of HGS is the use of antiviral agents such as acyclovir (Phillips, 2008). A recent systematic review found weak evidence that acyclovir is effective in reducing the number of oral lesions, preventing development of new lesions, and decreasing difficulty with eating and drinking (Nasser, Fedorowicz, Khoshnevisan, et al, 2008).

Nursing Care Management

The chief nursing goals for children with stomatitis are relief of pain and prevention of spread of the herpes virus. Analgesics and topical anesthetics are used as needed to provide relief, especially before meals to encourage food and fluid intake. For younger infants and toddlers who cannot swish and swallow, apply the diphenhydramine and Maalox solution with a cotton-tipped applicator before feedings to minimize pain. Educating parents regarding the use of these medications is important to maintain adequate hydration in the child whose mouth is too sore to take liquids. Drinking bland fluids through a straw is helpful in avoiding the painful lesions. Encourage mouth care; the use of a very soft bristle toothbrush or disposable foam-tipped toothbrush provides gentle cleaning near ulcerated areas.

Careful hand washing is essential when caring for children with HGS. Because the infection is autoinoculable, children should keep their fingers out of the mouth; contaminated hands can infect other body parts. Very young children may require elbow restraints to ensure compliance. Articles placed in the mouth are cleaned thoroughly. Newborns and individuals with immunosuppression should not be exposed to infected children.

Because herpes infection is often associated with sexual transmission, explain to parents and older children that HGS is usually caused by type 1 HSV, the type not associated with sexual activity.

Intestinal Parasitic Diseases

Intestinal parasitic diseases, including helminths (worms) and protozoa, constitute the most frequent infections in the world. In the United States the incidence of intestinal parasitic disease, especially giardiasis, has increased among young children who attend daycare centers. Young children are especially at risk because of typical hand-mouth activity and uncontrolled fecal activity.

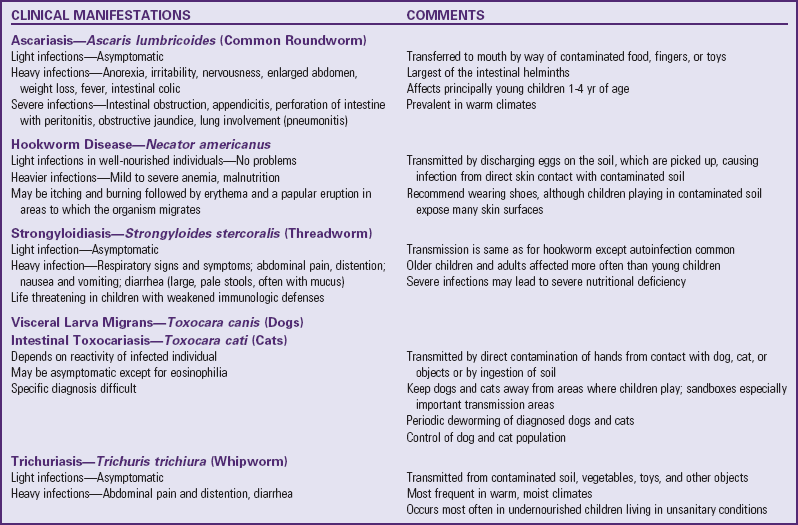

Various infecting organisms cause intestinal parasitic diseases in humans. This discussion is limited to the two most common parasitic infections among children in the United States: giardiasis and pinworms. Table 16-2 describes the outstanding features of selected helminths that belong to the family of nematodes.

General Nursing Care Management

Nursing responsibilities related to intestinal parasitic infections involve assistance with identification of the parasite, treatment of the infection, and prevention of initial infection or reinfection. Laboratory examination of substances containing the worm, its larvae, or ova can identify the organism. Most are identified by examining fecal smears from the stools of persons suspected of harboring the parasite. Fresh specimens are best for revealing parasites or larvae; therefore take collected specimens directly to the laboratory for examination. If this is not possible, place the specimen in a container with a preservative. Parents need clear instructions on obtaining an adequate sample and the number of samples required. (See Stool Specimens, Chapter 27.) In most parasitic infections, other family members, especially children, may be examined to identify those who are similarly affected.

After the diagnosis is confirmed and appropriate treatment is planned, parents need further explanation and reinforcement. Compliance in terms of drug therapy and other measures, such as thorough hand washing, is essential for eradication of the parasite. The family needs to understand the nature of transmission and that in some cases the medication must be repeated in 2 weeks to 1 month to kill organisms hatched since initial treatment.

The nurse’s most important function is preventive education of children and families regarding hygiene and health habits. Thorough hand washing before eating or handling food and after using the toilet is the most important precautionary method. The Family-Centered Care box lists other preventive practices.

Giardiasis

Giardiasis is caused by the protozoan Giardia lamblia (also called Giardia intestinalis, Giardia duodenalis, and Lamblia intestinalis). It is the most common intestinal parasitic pathogen in the United States. Child care centers and institutions providing care for persons with developmental disabilities are common sites for urban giardiasis, and the children may pass cysts for months. Also consider giardiasis in those with a history of recent travel to an endemic area (Yoder and Beach, 2007; Shields, Gleim, and Beach, 2008).

The potential for transmission is great, because the cysts—the nonmotile stage of the protozoa—can survive in the environment for months. Chief modes of transmission are person to person; food; and animals, especially puppies. Contaminated water, especially in mountain lakes and streams and swimming or wading pools frequented by diapered infants, are common sources of transmission. In children, person-to-person transmission is the most likely cause. Recent studies indicate swimming pool filters and interactive water fountains to be sites of contamination (Eisenstein, Bodager, and Ginzl, 2008; Shields, Gleim, and Beach, 2008). Although individuals infected with giardiasis may be asymptomatic, common symptoms include abdominal cramps and diarrhea (Box 16-2).

Diagnosis of giardiasis may be made by microscopic examination of stool specimens or duodenal fluid, or by identification of G. lamblia antigens in these specimens by techniques such as enzyme immunoassay (EIA). Because the Giardia organisms live in the upper intestine and are excreted in a highly variable pattern, repeated microscopic examination of stool specimens may be required to identify trophozoites (active parasites) or cysts. Duodenal specimens are obtained by direct aspiration, biopsy, or the string test. In the string test, the child swallows a gelatin capsule with a nylon string attached. Several hours later, the string is withdrawn and the contents are sent for laboratory analysis. With the availability of EIA techniques to identify Giardia antigens in stool specimens, other tests are being used less often.

Therapeutic Management

The drugs of choice for treatment of giardiasis are metronidazole (Flagyl), tinidazole (Tindamax), and nitazoxanide (Alinia). Tinidazole is said to have an 80% to 100% cure rate after a single dose (American Academy of Pediatrics, 2009). Metronidazole and tinidazole have a metallic taste and gastrointestinal side effects, including nausea and vomiting; nitazoxanide has no bitter taste and should be taken with food to avoid gastrointestinal symptoms. Albendazole is also used to treat the disease and reportedly has fewer side effects than metronidazole (American Academy of Pediatrics, 2009).

Nursing Care Management

The most important nursing consideration is prevention of giardiasis and education of parents, child care center staff, and those who assume the daily care of small children. Attention to meticulous sanitary practices, especially during diaper changes, is essential (see Family-Centered Care box and Fig. 16-8). Nurses can play an important role in educating parents of small children and daycare staff regarding appropriate sanitation practices. (See Alternative Child Care Arrangements, Chapter 12.) In addition, discourage young children who are infected or who have diarrhea from swimming in community or private pools until they are infection-free. Lakes and streams may contain high numbers of Giardia spore cysts, which can be swallowed in the water. Discourage children from swimming in stagnant bodies of water, and in water where there are known infected children swimming when there is a high chance of swallowing water. Giardia organisms are said to be resistant to chlorine (Eisenstein, Bodager, and Ginzl, 2008). Encourage parents to take small children to the restroom frequently when swimming, to avoid letting children in diapers in swimming areas, and to change diapers away from the water source. (See also Centers for Disease Control information on recreational water illnesses [www.cdc.gov/healthyswimming].) After children are infected, family education regarding drug administration is essential.

Fig. 16-8 Prevention of giardiasis, especially in daycare centers, requires sanitary practices during diaper changes, such as discarding paper diapers in a covered receptacle, changing paper covers on the diaper-changing surface, and having facilities for hand washing nearby. note: Soiled cloth diapers and clothing should be stored in a plastic bag for transport home.

Enterobiasis (Pinworms)

Enterobiasis, or pinworms, caused by the nematode Enterobius vermicularis, is the most common helminthic infection in the United States. It is universally present in temperate climatic zones and may infect more than 30% of all children at any one time. Crowded conditions, such as in classrooms and daycare centers, favor transmission.

Infection begins when the eggs are ingested or inhaled (the eggs float in the air). The eggs hatch in the upper intestine, then mature and migrate through the intestine. After mating, adult females migrate out the anus and lay eggs (American Academy of Pediatrics, 2009). The movement of the worms on skin and mucous membrane surfaces causes intense itching. As the child scratches, eggs are deposited on the hands and underneath the fingernails. The typical hand-to-mouth activity of youngsters makes them especially prone to reinfection. Pinworm eggs persist in the indoor environment for 2 to 3 weeks, contaminating anything they contact, such as toilet seats, doorknobs, bed linen, underwear, and food. Except for the intense rectal itching associated with pinworms, the clinical manifestations are nonspecific (Box 16-3).

Diagnostic Evaluation

Diagnosis is most commonly made from the tape test (see Nursing Care Management). Repeated tests to collect eggs may be necessary, and if there is a possibility that other family members may be infected, perform a tape test on them.

Therapeutic Management

The drugs available for treatment of pinworms include mebendazole (Vermox), pyrantel pamoate (Pin-Rid, Antiminth), and albendazole. The drug of choice is mebendazole, which is safe, effective, and convenient, with few side effects. However, it is not recommended for children younger than 2 years of age. If pyrvinium pamoate is prescribed, advise parents that the drug stains stool and vomitus bright red, as well as clothing or skin that comes in contact with the drug; it is available without prescription and should not be used in children under 2 years without consulting the primary practitioner. Because pinworms are easily transmitted, all household members are treated. The dose of antiparasitic medication should be repeated in 2 weeks to completely eradicate the parasite and prevent reinfection.

Nursing Care Management

Direct nursing care at identifying the parasite, eradicating the organism, and preventing reinfection. Parents need clear, detailed instructions for the tape test. A loop of transparent (not “frosted” or “magic”) tape, sticky side out, is placed around the end of a tongue depressor, which is then firmly pressed against the child’s perianal area. A convenient, commercially prepared tape is also available for this purpose. Pinworm specimens are collected in the morning as soon as the child awakens and before the child has a bowel movement or bathes. The procedure may need to be performed on 3 or more consecutive days before eggs are collected. Parents are instructed to place the tongue blade in a glass jar or loosely in a plastic bag so that it can be brought in for microscopic examination. For specimens collected in the hospital, practitioner’s office, or clinic, place the tape smoothly on a glass slide, sticky side down, for examination.

Adherence to the drug regimen is usually excellent since only one or two doses are needed. The family should be reminded of the need to take a second dose in 2 weeks to ensure eradication of the eggs.

To prevent reinfection, washing all clothes and bed linens in hot water and vacuuming the house may be recommended. However, there is little documentation on the effectiveness of these measures, since pinworms survive on many surfaces. Helpful suggestions include hand washing after toileting and before eating, keeping the child’s fingernails short to minimize the chance of ova collecting under the nails, dressing children in one-piece sleeping outfits, and daily showering rather than tub bathing. Inform families that recurrence is common. Treat repeated infections in the same manner as the first one.

Ingestion of Injurious Agents

![]() Since the passage of the Poison Prevention Packaging Act of 1970, which requires that certain potentially hazardous drugs and household products be sold in child-resistant containers, the incidence of poisonings in children has decreased dramatically. However, despite these advances, poisoning remains a significant health concern, with most cases (51% in 2007) occurring in children younger than 6 years of age (Bronstein, Spyker, Cantilena, et al, 2008). The home environment lends itself to injury in this vulnerable age-group of children (Dessypris, Dikalioti, Skalkidis, et al, 2009). Although pharmaceuticals such as analgesics, cough and cold preparations, topical preparations, antibiotics, vitamins, gastrointestinal preparations, hormones, and antihistamines are frequently the agents of poisonings, a variety of other substances can still poison children. The most frequently ingested poisons include (Bronstein, Spyker, Cantilena, et al, 2008; Franklin and Rodgers, 2008)*:

Since the passage of the Poison Prevention Packaging Act of 1970, which requires that certain potentially hazardous drugs and household products be sold in child-resistant containers, the incidence of poisonings in children has decreased dramatically. However, despite these advances, poisoning remains a significant health concern, with most cases (51% in 2007) occurring in children younger than 6 years of age (Bronstein, Spyker, Cantilena, et al, 2008). The home environment lends itself to injury in this vulnerable age-group of children (Dessypris, Dikalioti, Skalkidis, et al, 2009). Although pharmaceuticals such as analgesics, cough and cold preparations, topical preparations, antibiotics, vitamins, gastrointestinal preparations, hormones, and antihistamines are frequently the agents of poisonings, a variety of other substances can still poison children. The most frequently ingested poisons include (Bronstein, Spyker, Cantilena, et al, 2008; Franklin and Rodgers, 2008)*:

![]() Case Study—Ingestion of an Injurious Agent

Case Study—Ingestion of an Injurious Agent

• Cosmetics and personal care products (perfume, cologne, aftershave)

• Cleaning products (hypochlorite [household] bleach, pine oil disinfectants)

• Plants (nontoxic gastrointestinal irritants, oxalates) (Box 16-4)

• Foreign bodies, toys, and miscellaneous substances (desiccants, thermometers, bubble-blowing solutions)

Children are exposed to toxic substances more frequently than any other age-group (Eldridge, Van Eyk, and Kornegay, 2007). Many poisonings reflect the ready accessibility of the product in the home, where more than 90% of poisonings occur. A significant number of poisonings take place elsewhere, such as in a grandparent’s or friend’s home, in a school, or in a health care facility.

The developmental characteristics of young children predispose them to poisoning by ingestion. Infants and toddlers explore their environment through oral experimentation. Because their sense of taste is not discriminating at this age, they ingest many unpalatable substances. In addition, toddlers and preschoolers are developing autonomy and initiative, which increase their curiosity and noncompliant behavior. Imitation is also a powerful motivator, especially when combined with lack of awareness of danger.

This section is primarily concerned with the immediate emergency treatment of ingestion of injurious agents. ![]() Box 16-5 summarizes specific management of corrosive, hydrocarbon, acetaminophen, salicylate, iron, and plant poisoning. Because of the importance of lead poisoning among young children, ingestion of lead is discussed separately. Appropriate suggestions for poison prevention are discussed on p. 625 and in Chapter 14.

Box 16-5 summarizes specific management of corrosive, hydrocarbon, acetaminophen, salicylate, iron, and plant poisoning. Because of the importance of lead poisoning among young children, ingestion of lead is discussed separately. Appropriate suggestions for poison prevention are discussed on p. 625 and in Chapter 14.

![]() Case Study—Salicylate Ingestion

Case Study—Salicylate Ingestion

Principles of Emergency Treatment

![]() A poisoning may or may not require emergency intervention, but in every instance medical evaluation is necessary to initiate appropriate action. Advise parents to call the poison control center (PCC) before initiating any intervention. Parents should post the local PCC telephone number (usually listed in the front of the telephone directory) near each phone in the house† (see Critical Thinking Exercise and Emergency Treatment box).

A poisoning may or may not require emergency intervention, but in every instance medical evaluation is necessary to initiate appropriate action. Advise parents to call the poison control center (PCC) before initiating any intervention. Parents should post the local PCC telephone number (usually listed in the front of the telephone directory) near each phone in the house† (see Critical Thinking Exercise and Emergency Treatment box).

![]() Critical Thinking Exercise—Poisoning

Critical Thinking Exercise—Poisoning

Based on the initial telephone assessment, the PCC counsels the parents to begin treatment at home or to take the child to an emergency facility. When a call is taken, the name and telephone number of the caller is recorded to reestablish contact if the connection is interrupted. Because most poisonings are managed in the home, expert advice is essential in minimizing adverse effects. When the exact quantity or type of ingested toxin is not known, admission to a health care facility with pediatric emergency treatment services for laboratory evaluation and surveillance during the time after ingestion is critical.

Assessment

The first and most important principle in dealing with a poisoning is to treat the child first, not the poison. This requires an immediate concern for life support. Vital signs are taken, and respiratory or circulatory support is instituted as needed. The child’s condition is routinely reevaluated. Because shock is a complication of several types of household poisons, particularly corrosives, measures to reduce the effects of shock are important, beginning with the ABCs (airway, breathing, circulation) of resuscitation. Establishing and maintaining vascular access for rapid intravascular volume expansion is vital in the treatment of pediatric shock.

The emergency department nurse’s responsibility is to be prepared for immediate intervention with all of the necessary equipment. Because time and speed are critical factors in recovery from serious poisonings, anticipation of potential problems and complications may mean the difference between life and death.

Gastric Decontamination

Although pediatric poison ingestions are common, they rarely result in significant morbidity or mortality (Greene, Harris, and Singer, 2008). Consider using gastrointestinal decontamination (GID) only after careful evaluation of the potential toxicity of the poison and the risks versus benefits. When GID is needed, the immediate treatment is to remove the ingested poison by adsorbing the toxin with activated charcoal, performing gastric lavage, or increasing bowel motility (catharsis). Because of continuing controversy regarding the use of these methods, treat each toxic ingestion individually (Madden, 2008; Eldridge, Van Eyk, and Kornegay, 2007). Specific antidotes may be administered for certain poisonings.

Syrup of ipecac, an emetic that exerts its action through irritation of the gastric mucosa and by stimulation of the vomiting center, is no longer recommended for routine treatment of poison ingestion (American Academy of Pediatrics, 2009; Greene, Harris, and Singer, 2008; Sheffield and Serwint, 2008; Criddle, 2007). Box 16-6 lists the certain situations when ipecac may be of benefit.

Medications such as calcium channel blockers and benzodiazepines either produce a rapid onset of adverse symptoms (e.g., sedation, seizures, coma) or exaggerate the vagal response induced by gagging, which can lead to significant bradycardia. Under either circumstance, uncontrolled vomiting becomes an undesirable and unsafe event.

A more commonly used method of gastrointestinal decontamination is the use of activated charcoal (AC), an odorless, tasteless, fine black powder that adsorbs many compounds, creating a stable complex (Sheffield and Serwint, 2008). AC should be used in the following situations:

• Poison is potentially toxic.

• No contraindications exist to using AC.

• Poison ingested is bound by charcoal.

• Poison is likely to be in the gastrointestinal tract at the time of AC administration.

• Gastrointestinal tract is intact.

• No safer or more effective alternative therapy is available.

AC is mixed with water or a saline cathartic to form a slurry. Slurries are neither gritty nor distasteful but resemble black mud. To increase the child’s acceptance of AC, the nurse should mix it with diet soda and serve it through a straw in an opaque container with a cover (such as a disposable coffee cup and lid) or an ordinary cup covered with aluminum foil or placed inside a small paper bag. In one small study, healthy adolescents preferred the taste of AC mixed with cola or chocolate milk mixture instead of water (Cheng and Ratnapalan, 2007). For small children a nasogastric tube may be required to administer AC (Greene, Harris, and Singer, 2008).

There is discussion of the use of AC in the home for pediatric poison ingestion. The evidence is not clear regarding the risk versus benefit of home AC administration (Eldridge, Van Eyk, and Kornegay, 2007). Potential complications from the use of AC include aspiration (usually in patients with impaired gag reflexes), constipation, and intestinal obstruction (in multiple doses) (Sheffield and Serwint, 2008). Superactivated charcoal products for gastric decontamination are often more palatable and just as effective (Criddle, 2007).

If the child is admitted to an emergency facility, gastric lavage may be performed to empty the stomach of the toxic agent; however, this procedure can be associated with serious complications (gastrointestinal perforation, hypoxia, aspiration) and it is no longer recommended in all cases of ingestion. There is no conclusive evidence that gastric lavage decreases morbidity (Greene, Harris, and Singer, 2008; Sheffield and Serwint, 2008; Criddle, 2007). In addition, gastric lavage may be of little benefit if used later than 1 hour after ingestion (Greene, Harris, and Singer, 2008). Conditions that may be appropriate for the use of gastric lavage include presentation within 1 hour of ingestion of a toxin, ingestion in patient who has decreased gastrointestinal motility, the ingestion of a toxic amount of sustained-release medication, and a massive or life-threatening amount of poison (Madden, 2008; Criddle, 2007). When gastric lavage is used, the patient requires a protected airway, possible sedation, and the largest-diameter tube that can be inserted to facilitate passage of gastric contents. The Evidence-Based Practice box reviews recent literature on the use of gastric lavage in comparison to AC when a child has ingested poison.

In a minority of poisonings, specific antidotes are available to counteract the poison. They are highly effective and should be available in all emergency facilities. The supply of antidotes should be checked routinely and replaced as used or according to expiration dates. Antidotes available to treat toxin ingestion include N-acetylcysteine for acetaminophen poisoning, oxygen for carbon monoxide inhalation, naloxone for opioid overdose, flumazenil (Romazicon) for benzodiazepines (diazepam [Valium], midazolam [Versed]) overdose, digoxin immune Fab (Digibind) for digoxin toxicity, amyl nitrate for cyanide, and antivenin for certain poisonous bites.

Prevention of Recurrence

The ultimate objective is to prevent poisonings from occurring or recurring. Home safety education improves poison-prevention practices (Kendrick, Smith, Sutton, et al, 2008). Research supports the effectiveness of parent education on preventing unintentional injuries (Kendrick, Barlow, Hampshire, et al, 2007; Kendrick, Coupland, Mulvaney, et al, 2007). One effective counseling method is first to discuss the difficulties of constantly watching and safeguarding young children (see Family-Centered Care box). In this way the challenging task of raising children can lead to a discussion of injury prevention as part of the parental role. This approach also incorporates contributory causes for the incident, such as inadequate support systems; marital discord; discipline techniques (especially use of physical punishment); and any disruption in the family or family activities, such as vacations, moves, visitors, illnesses, or births. A visit to the home, especially after repeat poisonings, is recommended as part of the follow-up care to assess hazards, including family factors, and to evaluate appropriate injury-proofing measures. One method of identifying risk areas is to ask specific questions or to have the parent complete a questionnaire designed to isolate factors that predispose children to poisoning. Another approach is to encourage parents to bend down to the child’s eye level and survey the home environment for potential hazards. Have the parents try to open cabinets and reach shelves to access poisons.

Passive measures (those that do not require active participation) have been the most successful in preventing poisoning and include using child-resistant closures and limiting the number of tablets in one container. However, these measures alone are not sufficient to prevent poisoning, since most toxic agents in the home do not have safety closures. Therefore active measures (those that require participation) are essential. The Nursing Care Guidelines box lists the guidelines for preventing the occurrence or recurrence of a poisoning.

Heavy Metal Poisoning

![]() Heavy metal poisoning can occur from the ingestion of a variety of substances, the most common being lead. Other sources that are important in terms of children are iron and mercury. Mercury toxicity, a rare form of heavy metal poisoning, has occurred in children from a variety of sources, such as broken thermometers or thermostats, broken fluorescent light bulbs, disk batteries, topical medications, gas regulators, cathartics, and interior latex house paint (Clifton, 2007). Elemental mercury (also called metallic mercury or quicksilver) is nontoxic if ingested and if the gastrointestinal tract is healthy (e.g., has no fistulas). However, mercury is volatile at room temperature and enters the bloodstream after it is inhaled, causing toxicity (tremors, memory loss, insomnia, gingivitis, diarrhea, anorexia, weight loss). The classic form of mercury poisoning is called acrodynia (or “painful extremities”).

Heavy metal poisoning can occur from the ingestion of a variety of substances, the most common being lead. Other sources that are important in terms of children are iron and mercury. Mercury toxicity, a rare form of heavy metal poisoning, has occurred in children from a variety of sources, such as broken thermometers or thermostats, broken fluorescent light bulbs, disk batteries, topical medications, gas regulators, cathartics, and interior latex house paint (Clifton, 2007). Elemental mercury (also called metallic mercury or quicksilver) is nontoxic if ingested and if the gastrointestinal tract is healthy (e.g., has no fistulas). However, mercury is volatile at room temperature and enters the bloodstream after it is inhaled, causing toxicity (tremors, memory loss, insomnia, gingivitis, diarrhea, anorexia, weight loss). The classic form of mercury poisoning is called acrodynia (or “painful extremities”).

![]() Case Study—Heavy Metal Poisoning

Case Study—Heavy Metal Poisoning

Heavy metals have an affinity for certain essential tissue chemicals, which must remain free for adequate cell functioning. When metals are bound to these substances, cellular enzyme systems are inactivated. Treatment involves chelation, use of a chemical compound that combines with the metal for rapid and safe excretion.

Lead Poisoning

Poisoning from lead has been a problem throughout history and throughout the world. In the United States the problem became apparent in the early 1900s when white lead was added to paints and when tetraethyl lead was added to gasoline as an antiknock compound. Lead content in paint was decreased in 1950, and in 1978 the use of lead in household paint was banned. The use of lead in paint and leaded gasoline has been banned in the United States. After this change in policy, the average blood lead level (BLL) in the United States for people ages 1 to 74 years dropped from 12.8 mcg/dl in 1980 to 1.9 mcg/dl in 1999 (American Academy of Pediatrics, 2005). However, children continue to be exposed to lead; an estimated 1.6% of U.S. children had BLLs of more than 10 mcg/dl in 2002, and almost 14% had BLLs of 5 to 9 mcg/dl (Levin, Brown, Kashtock, et al, 2008).

Causes of Lead Poisoning

Although there are numerous sources of lead (Box 16-7), in most instances of acute childhood lead poisoning, the source is nonintact lead-based paint in an older home or lead-contaminated bare soil in the yard. Microparticles of lead gain entrance into a child’s body through ingestion or inhalation and, in the case of an exposed pregnant woman, by placental transfer. When measured, a mother’s lead level is nearly the same as that of her unborn child. However, though the level of lead may not be harmful to an adult woman, it can be harmful to the fetus.

Inhalation exposure usually occurs during renovation and remodeling activities in the home, whereas ingestion happens during normal day-to-day play and mouthing activities. Sometimes a child will actually swallow loose chips of lead-based paint because it has a sweet taste. Water and food may also be contaminated with lead. A child does not need to eat loose paint chips to be exposed to the toxin; normal hand-to-mouth behavior, coupled with the presence of lead dust in the environment that has settled over the decades, is the usual method of poisoning (Frazer, 2008; American Academy of Pediatrics, 2005; Erickson and Thompson, 2005).

Because of family, cultural, or ethnic traditions, a source of lead may be a routine part of life for a child. Nurses must educate themselves about the practices of their patients and identify when such products may be a source of lead. The use of pottery or dishes containing lead may be an issue, as may the use of folk remedies for stomachaches or the use of some cosmetics (see Cultural Competence box). Children of immigrants and internationally adopted children may have been exposed to sources of lead before arrival in the United States and should also be carefully evaluated for lead exposure (Woolf, Goldman, and Bellinger, 2007). Other risk factors for having an elevated BLL include living in poverty, being less than 6 years of age, dwelling in urban areas, and living in older rental homes where lead decontamination may not be a priority. Nurses are often in a position to observe or elicit information about these practices and educate families about their potential harm.

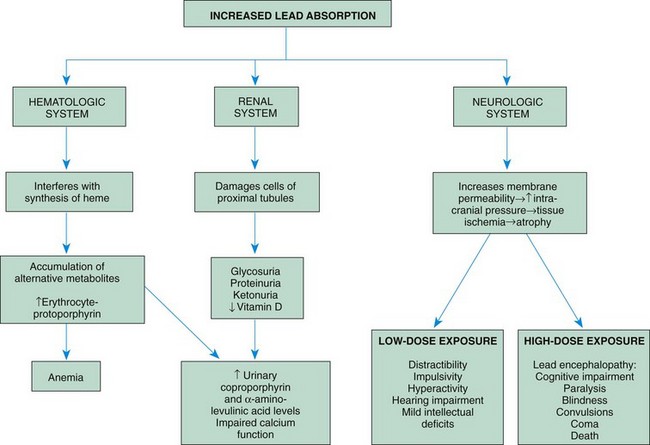

Pathophysiology and Clinical Manifestations

Lead can affect any part of the body, including the renal, hematologic, and neurologic systems (Fig. 16-9). Of most concern for young children is the developing brain and nervous system, which are more vulnerable than those of an older child or adult. Lead in the body moves via an equilibration process between the blood, the soft tissues and organs, and the bones and teeth. Lead ultimately settles in the bones and teeth, where it remains inert and in storage. This makes up the largest portion of the body burden, approximately 75% to 90%. At the cellular level it competes with molecules of calcium, interfering with the regulating action of calcium. In the brain, lead disrupts the biochemical processes and may have a direct effect on the release of neurotransmitters, may cause alterations in the blood-brain barrier, and may interfere with the regulation of synaptic activity (Lidsky and Schneider, 2006).

There is a relationship between anemia and lead poisoning. Children who are iron deficient absorb lead more readily than those with sufficient iron stores. Lead can interfere with the binding of iron onto the heme molecule. This sometimes creates a picture of anemia, even though the child is not iron deficient. Lead toxicity to the erythrocytes leads to the release of the enzyme erythrocyte protoporphyrin (EP). Because EP is not sensitive to BLLs of less than about 16 to 25 mcg/dl, it is no longer used as a screening test. Therefore the BLL test is currently used for screening and diagnosis. However, elevation of the EP level (>35 mcg/dl of whole blood) is a good indicator of toxicity from lead and reflects the length of exposure and body burden of lead in the individual child.

Although adults have been shown to suffer adverse renal effects from occupational lead exposure, few studies document renal effects in children except at extremely high lead levels. One can hypothesize that lead can affect the renal integrity of children as well as adults. Therefore the renal system of a child is still considered a potential target for the harmful effects of lead.

The lead levels identified in children have declined since the initiation of screening for children at risk for lead poisoning. With earlier intervention, the most prevalent effects have changed. Since the late 1960s, children have rarely died of lead poisoning, and seizures or cognitive impairment have become less likely. However, even mild and moderate lead poisoning can cause a number of cognitive and behavioral problems in young children, including aggression, hyperactivity, impulsivity, delinquency, disinterest, and withdrawal. Long-term neurocognitive signs of lead poisoning include developmental delays, lowered intelligence quotient (IQ), reading skill deficits, visual-spatial problems, visual-motor problems, learning disabilities, and lower academic success. Chronic lead toxicity may also affect physical growth and reproductive efficiency (Woolf, Goldman, and Bellinger, 2007).

Diagnostic Evaluation

Children with lead poisoning rarely have symptoms, even at levels requiring chelation therapy. A diagnosis of lead poisoning is based only on the lead testing of a venous blood specimen from a venipuncture. The collection process is important. Blood must be collected carefully to avoid contamination by lead on the skin. The level of concern for an elevated BLL has dropped from 80 mcg/dl in 1950 to 10 mcg/dl today (Heavey, 2008).

Anticipatory Guidance

Anticipatory guidance lends support to primary prevention efforts. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2005) recommend that the following information be made available to families beginning during prenatal care, at 3 to 6 months, and at 1 year of age:

• Hazards of lead-based paint in older housing

• Ways to control lead hazards safely

• Hazards accompanying repainting and renovation of homes built before 1978

• Other exposure sources, such as traditional remedies, that might be relevant for a family

There has been recent concern regarding toys and other imported items children play with which were found to contain lead. Parents should carefully evaluate the source of the toy (manufacturer) or item the child may play with and not assume it is safe because it is sold in a U.S. market. The U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission (www.cpsc.gov) is an excellent resource for parents and caregivers concerned about the safety of a given toy or product that may be harmful.

Screening for Lead Poisoning

When primary prevention fails, secondary prevention screening efforts for elevated BLLs can identify children much earlier than in the past. Guidelines recommend universal or targeted screening (Levin, Brown, Kashtock, et al, 2008). This need is established using blood lead surveillance and other risk factor data collected over time to establish the status and risk of children throughout the state. In areas without available data, universal screening is recommended.

Universal screening should be done at ages 1 and 2 years. Any child between the ages of 3 and 6 years who has not been previously screened should also be tested. Screen any child with risk factors more often.

Targeted screening is acceptable when an area has been determined by existing data to have less risk. Children should be screened when they live in a high-risk geographic area or are members of a group determined to be at risk (e.g., Medicaid recipients), or if their family cannot answer “no” to the following personal risk questions:

• Does your child live in or regularly visit a house that was built before 1950?

• Does your child live in or regularly visit a house built before 1978 with recent or ongoing renovations or remodeling within the past 6 months?

• Does your child have a sibling or playmate who has or did have lead poisoning?

Therapeutic Management

The degree of concern, urgency, and need for medical intervention changes as the lead level increases. Education is one of the most important elements of the treatment process. Several areas that the nurse needs to discuss with the family of every child who has an elevated BLL (≥10 mcg/dl) include (Heavey, 2008; Levin, Brown, Kashtock, et al, 2008):

• The child’s BLL and what it means

• Potential adverse health effects of an elevated BLL

• Sources of lead exposure and suggestions on how to reduce exposure, such as importance of wet cleaning to remove lead dust on floors, window sills, and other surfaces

• Importance of good nutrition in reducing the absorption and effects of lead; for persons with poor nutritional patterns, adequate intake of calcium and iron and importance of regular meals

• Need for follow-up testing to monitor the child’s BLL

• Results of an environmental investigation if applicable

• Hazards of improper removal of lead paint (dry sanding, scraping, or open-flame burning)

Treatment actions vary depending on the child’s BLL. Based on a diagnosis from a venous BLL test, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2002) recommend the following actions:

| BLL (mcg/dl) | Action |

| <10 | Reassess or rescreen in 1 year. If exposure status changes, do this sooner. |

| 10-14 | Provide family with lead poisoning education, follow-up testing, and social service referral if necessary. |

| 15-19 | Provide family with lead poisoning education (dietary and environmental), follow-up testing, and social service referral as needed; if BLL persists, initiate actions for BLL of 20 to 44 mcg/dl. |

| 20-44 | Provide coordination of care, clinical management, environmental investigation, and lead hazard control. |

| 45-69 | Within 48 hours, provide coordination of care and clinical management, including treatment, environmental investigation, and lead hazard control. The child must not remain in a lead-hazardous environment if resolution is to occur. |

| ≥70 | Immediately provide medical treatment and begin coordination of care, clinical management, environmental investigation, and lead hazard control. |

Chelation Therapy: Chelation is the term used for removing lead from circulating blood and, theoretically, some lead from organs and tissues. It is unclear whether chelation affects lead stores in bones. Although not an antidote in the truest sense, it does serve a similar purpose in that the toxic substance or poison is removed from the body. However, chelation does not counteract any effects of the lead.

Historically two chelating agents have been used consistently: calcium disodium edetate (CaNa2EDTA, or calcium EDTA) and succimer (Chemet, meso-2,3-dimercaptosuccinic acid [DMSA]). British antilewisite (BAL, dimercaprol, dimercaptopropanol) is used in conjunction with EDTA. All the agents have potential toxic side effects and contraindications. Monitor renal, hepatic, and hematologic parameters.

Because of the equilibration process between blood, soft tissues, and other sites in the body, there is often a rebound of the BLL after chelation. After the body burden of lead is reduced enough to stabilize the BLL, rebound will cease. Multiple chelation treatments may be necessary. Adequate hydration is essential during therapy because the chelates are excreted via the kidneys.

BAL must not be used in the presence of a glucose 6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency or peanut allergy, nor should it be given in conjunction with iron. It is never used as a single-agent therapy, only in conjunction with EDTA. It must be given only at a deep intramuscular site. EDTA should be given intravenously over several hours or, when necessary to restrict fluids, may be given intramuscularly.

Succimer is given orally over a 19-day course of treatment. The capsule is opened and sprinkled on a small amount of food or may be swallowed whole. Adverse effects include nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, loss of appetite, rash, elevated liver function tests, and neutropenia. Because the chelates are excreted via the kidneys, adequate hydration is essential.

An oral chelating agent, d-penicillamine, is sometimes used to treat lead poisoning, but low doses should be used in children. Monitoring of renal function and blood counts during administration is essential (Woolf, Goldman, and Bellinger, 2007).

Prognosis: Although most of the pathophysiologic effects of lead are reversible, the most serious consequences of both high and low lead exposure are the effects on the central nervous system. In children with lead encephalopathy, permanent brain damage can result in cognitive impairment, behavior changes, possible paralysis, and seizures. However, moderate- to low-dose exposure may also cause permanent neurologic deficits. Increased distractibility, short attention span, impulsivity, reading disabilities, and school failure have been associated with lead exposure. There is some evidence that treatment of moderate levels of lead poisoning can result in cognitive improvement (American Academy of Pediatrics, 2005).

Nursing Care Management

The primary nursing goal in lead poisoning is to prevent the child’s initial or further exposure to lead. For children with low-level exposure, this requires identifying the sources of lead in the environment. Careful history taking is the most useful and most valuable tool and should concentrate on the personal risk questions (see p. 629). Suggestions for reducing lead in the child’s environment are listed in the Community Focus box.

For children who undergo chelation therapy, the nurse prepares them for the injections and makes all efforts to reduce injection pain. Chelating agents are administered deeply into a large muscle mass (see Atraumatic Care box). To lessen the pain from EDTA, the local anesthetic procaine is injected with the drug. Rotation of sites is essential to prevent the formation of painful areas of fibrotic tissue. Because EDTA and lead are toxic to the kidneys, keep records of intake and output, and assess the results of urinalysis to monitor renal functioning.

Discharge planning for children with lead poisoning must include thorough education of families regarding safety from lead hazards, clear instructions regarding medication administration and follow-up, and confirmation that the child will be discharged to a home without lead hazards. Although the nurse must use caution to avoid alarming parents unnecessarily, it is important that they know the risk implications for their child’s behavior and cognitive functions. Nurses should observe the development and behavior of children who are hospitalized. Thoroughly evaluate any concerns that are identified. Referral to a child development or speech and language specialist may be necessary.

As in any situational crisis, parents need support and understanding if their child is treated for lead poisoning. Many families at the highest risk for lead poisoning have the fewest resources to comply with measures such as relocation or removal of lead from the environment where the child experiences exposure.

Child Maltreatment

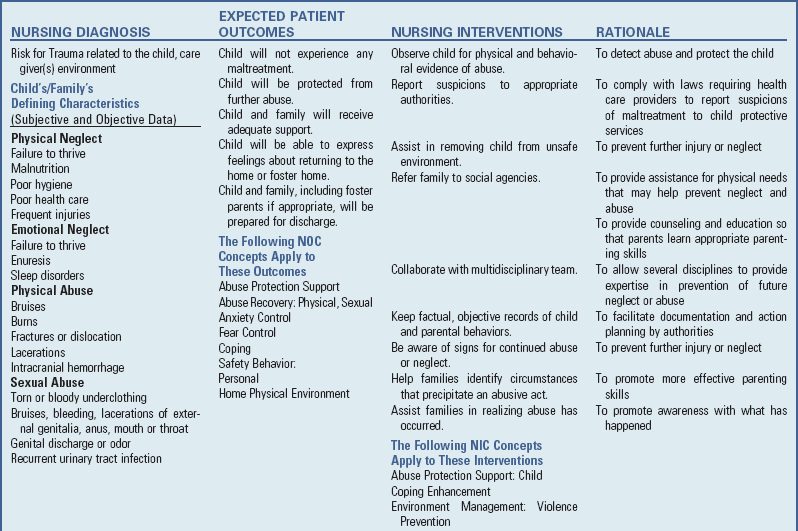

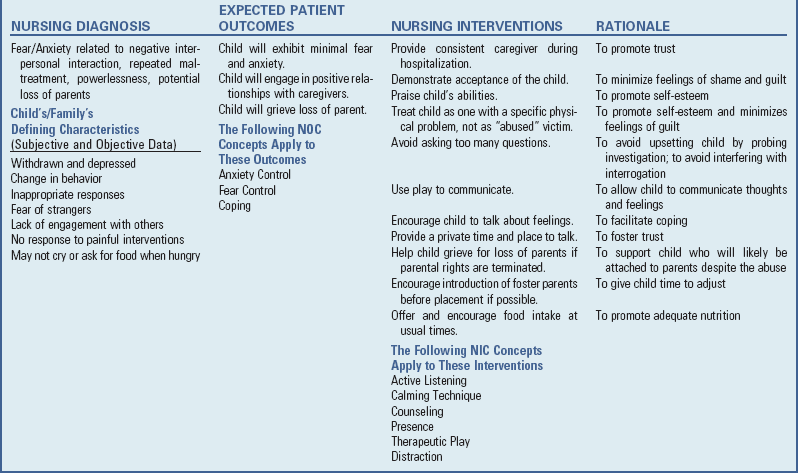

![]() The broad term child maltreatment includes intentional physical abuse or neglect, emotional abuse or neglect, and sexual abuse of children, usually by adults. It is one of the most significant social problems affecting children. In 2007 Child Protective Service (CPS) agencies in the United States confirmed that an estimated 794,000 children were victims of child maltreatment. Of the confirmed cases, about 11% suffered physical abuse, 8% sexual abuse, 60% neglect, and 4% psychologic maltreatment or emotional abuse. In 2007 there were an estimated 1760 child fatalities as a result of child abuse and neglect (US Department of Health and Human Services, 2009). Reported statistics only partially represent the actual incidence of child maltreatment, since many cases are believed to go unreported.*

The broad term child maltreatment includes intentional physical abuse or neglect, emotional abuse or neglect, and sexual abuse of children, usually by adults. It is one of the most significant social problems affecting children. In 2007 Child Protective Service (CPS) agencies in the United States confirmed that an estimated 794,000 children were victims of child maltreatment. Of the confirmed cases, about 11% suffered physical abuse, 8% sexual abuse, 60% neglect, and 4% psychologic maltreatment or emotional abuse. In 2007 there were an estimated 1760 child fatalities as a result of child abuse and neglect (US Department of Health and Human Services, 2009). Reported statistics only partially represent the actual incidence of child maltreatment, since many cases are believed to go unreported.*

![]() Nursing Care Plan—The Child Who Is Maltreated

Nursing Care Plan—The Child Who Is Maltreated

Child Neglect

Child neglect is the most common form of maltreatment. More than half of all reported cases are associated with deprivation of necessities, and 34% of deaths from maltreatment are in this group (US Department of Health and Human Services, 2009). Neglect is generally defined as the failure of a parent or other person legally responsible for the child’s welfare to provide for the child’s basic needs and an adequate level of care.

Important contributing factors for child neglect are lack of knowledge of child’s needs, lack of resources, and caregiver substance abuse. For example, neglectful parents often demonstrate poor parenting skills. They may be unaware that an infant needs to be fed every 3 to 4 hours, may not know what to feed the child, and may have insufficient funds to buy food. The most serious lack of knowledge is failure to recognize emotional nurturing as an essential need of children. (See also Growth Failure [Failure to Thrive], Chapter 13.)

Types of Neglect

Neglect takes many forms and can be classified broadly as physical or emotional maltreatment. Physical neglect involves the deprivation of necessities, such as food, clothing, shelter, supervision, medical care, and education. Emotional neglect generally refers to failure to meet the child’s needs for affection, attention, and emotional nurturance.

Neglect may also include lack of intervention for or fostering of maladaptive behavior, such as delinquency or substance abuse. Emotional abuse or psychologic maltreatment, an even more difficult aspect of maltreatment to define, refers to the deliberate attempt to destroy or significantly impair a child’s self-esteem or competence. Emotional abuse may take the form of rejecting, isolating, terrorizing, ignoring, corrupting, verbally assaulting, or overpressuring the child (Nelms, 2001).

Physical Abuse

![]() The deliberate infliction of physical injury on a child, usually by the child’s caregiver, is termed physical abuse. Legal definitions of physical abuse are found in state and federal statutes. The Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act of 1996 defines abuse as “any recent act or failure to act that results in imminent risk of serious harm, death, serious physical or emotional harm of a child (<18 years) by a parent or caregiver who is responsible for the child’s welfare.” Each state defines abuse according to its reporting laws. Minor physical injury is responsible for more reported cases of maltreatment than major physical injury, but major physical abuse causes more deaths. Despite the importance of the problem, a universally accepted definition of what constitutes minor and major physical abuse does not exist. Rather, each state in the United States defines abuse according to its individual reporting laws.

The deliberate infliction of physical injury on a child, usually by the child’s caregiver, is termed physical abuse. Legal definitions of physical abuse are found in state and federal statutes. The Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act of 1996 defines abuse as “any recent act or failure to act that results in imminent risk of serious harm, death, serious physical or emotional harm of a child (<18 years) by a parent or caregiver who is responsible for the child’s welfare.” Each state defines abuse according to its reporting laws. Minor physical injury is responsible for more reported cases of maltreatment than major physical injury, but major physical abuse causes more deaths. Despite the importance of the problem, a universally accepted definition of what constitutes minor and major physical abuse does not exist. Rather, each state in the United States defines abuse according to its individual reporting laws.

Shaken Baby Syndrome

Shaken baby syndrome (SBS) is a serious form of child abuse caused by violent shaking of infants and young children and is one form of abusive head trauma. Physicians commonly use more general terms, including abusive head trauma, inflicted head injury, or neuroinflicted brain injury; these terms do not assume the mechanism of injury, but rather describe the injury itself (Chiesa and Duhaime, 2009). This violent shaking would be easily recognized by others as dangerous (American Academy of Pediatrics, 2001) and is most often a result of the caregiver’s frustration with crying (Castiglia, 2001). Every year in America an estimated 1200 to 1400 children are shaken, and of these victims 25% to 30% die as a result of their injuries. The rest have life-long complications (National Center on Shaken Baby Syndrome, n.d.).

It is important to understand what happens in SBS. Infants have a large head-to-body ratio, weak neck muscles, and a large amount of water in the brain. Violent shaking causes the brain to rotate within the skull, resulting in shearing forces that tear blood vessels and neurons. The characteristic injuries that occur are intracranial bleeding (subdural and subarachnoid hematomas) and, in approximately 85% of cases, retinal hemorrhages, which are classic results of repetitive acceleration-deceleration head trauma (Levin, 2009). Injuries may also include fractures of the ribs and long bones. Most often there are no signs of external injury. SBS is often not an isolated event, and in one study 45% of the children with inflicted traumatic brain injury caused by shaking showed some evidence of prior injury (Ewing-Cobb, Kramer, Prasad, et al, 1998). Victims of SBS can be seen with a variety of symptoms, from generalized flulike symptoms to unresponsiveness with impending death (Miehl, 2005). Many of the presenting symptoms, such as vomiting, irritability, poor feeding, and listlessness, are often mistaken for common infant and childhood ailments. In more severe forms presenting symptoms may include seizures, posturing, alterations in level of consciousness, apnea, bradycardia, or death. The long-term outcomes of SBS include seizure disorders; visual impairments, including blindness; developmental delays; hearing loss; cerebral palsy; and mild to profound mental, cognitive, or motor impairments (Walls, 2006). Nurses can take an active role in prevention of SBS by teaching all caregivers about crying and techniques to cope with inconsolable crying (Carbaugh, 2004).

Munchausen Syndrome by Proxy

Munchausen syndrome by proxy (MSBP), also known as medical child abuse or factitious disorder by proxy, is a rare but serious form of child abuse in which caregivers deliberately exaggerate or fabricate histories and symptoms or induce symptoms. It is a form of child maltreatment that may include physical, emotional, and psychologic abuse for the gratification of the caregiver. In most cases the perpetrator is the biologic mother, with some degree of health care knowledge and training. Health care providers can become easily misled and unknowingly enable the perpetrator (Leider, Irving, Mauricio, et al, 2005). Because of the history of symptoms provided by the caregiver, the child endures painful and unnecessary medical testing and procedures. Common symptoms presented are seizures, nausea and vomiting, diarrhea, and altered mental status; they are usually witnessed only by the perpetrator.

Considerations when determining whether a child is a victims of MSBP include:

• Is the child’s condition consistent with the reported history?

• Does diagnostic evidence support the reported history?

• Has anyone other than the caregiver witnessed the symptoms?

• Is treatment being provided primarily because of the caregiver’s demands?

The resolution of symptoms after separation from the perpetrator confirms the diagnosis.

Factors Predisposing to Physical Abuse

![]() The causes of child abuse are multifaceted. Child maltreatment occurs across all socioeconomic, religious, cultural, racial, and ethnic groups (Goldman, Salus, Wolcott, et al, 2003). Three risk factors are commonly identified in child abuse: parental characteristics, characteristics of the child, and environmental characteristics. However, no single factor or group of factors is predictive of abuse. Rather, the interaction of these factors is thought to increase the risk of abuse occurring in a particular family.

The causes of child abuse are multifaceted. Child maltreatment occurs across all socioeconomic, religious, cultural, racial, and ethnic groups (Goldman, Salus, Wolcott, et al, 2003). Three risk factors are commonly identified in child abuse: parental characteristics, characteristics of the child, and environmental characteristics. However, no single factor or group of factors is predictive of abuse. Rather, the interaction of these factors is thought to increase the risk of abuse occurring in a particular family.

![]() Case Study—Behaviors Indicative of Future Child Abuse

Case Study—Behaviors Indicative of Future Child Abuse

Parental Characteristics: Some identified characteristics occur more frequently in parents who abuse their children and are therefore considered risk factors. Younger parents more often are abusers of their children. Single-parent families are at higher risk for abuse, and in single-parent families that include an unrelated partner, the partner is sometimes the abuser, although a biologic parent is most commonly the perpetrator (US Department of Health and Human Services, 2009).

Abusive families are often socially isolated and have few supportive relationships. They often have additional stressors such as low-income circumstances, with little education. Parents with substance abuse problems pose a greater risk for abuse and neglect due to a variety of factors. The additional stressors of substance abuse with the demands of normal care of children create situations where abuse and neglect can occur, since these parents have impaired judgment and may react with violence while under the influence of drugs or alcohol (Wells, 2009). With little or no available support system and concurrent stressors imposed by the child or environment, these parents are vulnerable to additional crises of any nature and may strike out at the child as a method of releasing their frustration and anxiety.