Liver disease

Acute and subacute liver failure

Liver failure arises from a number of insults to liver cells, principally viral infections or the toxic effects of drugs and chemicals. In the UK, paracetamol poisoning (Ch. 53) is the most common cause of acute liver failure.

Presenting symptoms of liver failure are often non-specific, with malaise, nausea and abdominal pain. As the syndrome progresses, signs of impairment of brain function occur (hepatic encephalopathy) with initial confusion followed by drowsiness and coma. These clinical features reflect alterations in neurotransmitter synthesis and increased central nervous system neuroinhibition with astrocyte swelling, caused by endogenous toxins that the liver fails to remove. Failure of coagulation and progressive multi-organ failure often follow.

The syndrome of liver failure can be categorised by the speed of onset of encephalopathy after the onset of jaundice:

hyperacute: onset within 7 days, typically due to paracetamol or hepatitis A or E virus,

hyperacute: onset within 7 days, typically due to paracetamol or hepatitis A or E virus,

acute: onset between 7 and 28 days, typically due to hepatitis B virus,

acute: onset between 7 and 28 days, typically due to hepatitis B virus,

subacute: onset between 29 days and 12 weeks; in this form, ascites and renal failure may also be prominent: typically due to non-paracetamol drug-induced injury.

subacute: onset between 29 days and 12 weeks; in this form, ascites and renal failure may also be prominent: typically due to non-paracetamol drug-induced injury.

Management

Acetylcysteine should be given if paracetamol was the precipitant (Ch. 53) and it may be useful in other forms of acute liver failure if treatment is started early when there is only low-grade encephalopathy. Other management is supportive and includes:

prevention of bacterial and fungal infection with broad-spectrum antibacterial and antifungal agents,

prevention of bacterial and fungal infection with broad-spectrum antibacterial and antifungal agents,

prevention of cerebral oedema by appropriate fluid management and particularly correction of hyponatraemia and the consequent hypo-osmolality. Cerebral oedema can be reduced by sedation and mechanical ventilation. Cerebral oedema is usually associated with encephalopathy, and is most marked in those who develop systemic infection, probably due to the interaction between pro-inflammatory mediators and circulating neurotoxins such as ammonia,

prevention of cerebral oedema by appropriate fluid management and particularly correction of hyponatraemia and the consequent hypo-osmolality. Cerebral oedema can be reduced by sedation and mechanical ventilation. Cerebral oedema is usually associated with encephalopathy, and is most marked in those who develop systemic infection, probably due to the interaction between pro-inflammatory mediators and circulating neurotoxins such as ammonia,

prevention of hypoglycaemia with intravenous glucose,

prevention of hypoglycaemia with intravenous glucose,

control of coagulopathy with intravenous vitamin K (Ch. 11), or fresh frozen plasma or cryoprecipitate if there is active bleeding,

control of coagulopathy with intravenous vitamin K (Ch. 11), or fresh frozen plasma or cryoprecipitate if there is active bleeding,

treatment of shock, often with a vasoconstrictors such as terlipressin (see below),

treatment of shock, often with a vasoconstrictors such as terlipressin (see below),

artificial support for renal failure by maintaining circulating blood volume and, if necessary, with haemofiltration or haemodialysis,

artificial support for renal failure by maintaining circulating blood volume and, if necessary, with haemofiltration or haemodialysis,

emergency liver transplantation is necessary for many people.

emergency liver transplantation is necessary for many people.

Chronic liver disease

There are many causes of chronic liver disease, most of which ultimately lead to fibrotic changes in the liver that eventually alter the liver architecture and lead to distortion of the vasculature within the liver. This advanced change is called cirrhosis, and in the UK is most often caused by alcohol or hepatitis C virus. Hepatitis B virus is the most common cause in many developing countries. Other causes include autoimmune liver disease, haemochromatosis, Wilson's disease and α1-antitrypsin deficiency. The diagnosis of liver cirrhosis is often made when complications arise (often referred to as decompensated cirrhosis), which include development of ascites, variceal haemorrhage, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis and hepatic encephalopathy (see below).

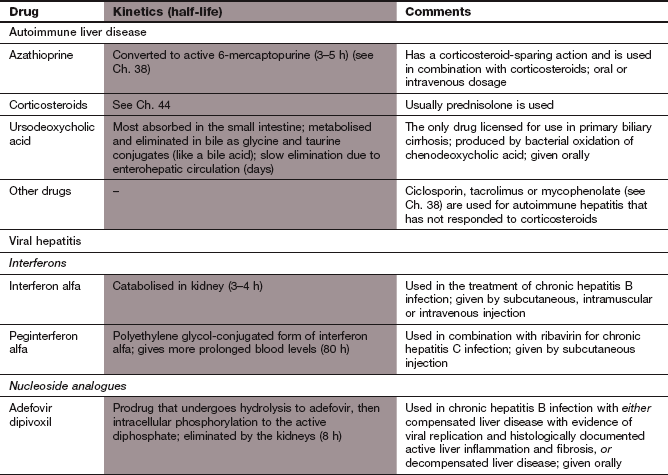

Autoimmune liver disease

There are three principal forms of autoimmune liver disease: autoimmune hepatitis (AIH), primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC) and primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC). The pathogenesis of these diseases is poorly understood, but the occurrence of circulating autoantibodies (antinuclear antibodies and smooth muscle antibodies, antibodies to liver/kidney microsome type 1 in AIH, antimitochondrial antibodies in PBC and low titres of several autoantibodies in PSC) and T-lymphocytes in the inflammatory infiltrate in the liver has encouraged the use of immunosuppressant treatments. Without treatment, AIH usually progresses to cirrhosis.

Management

Corticosteroids, usually prednisolone (Ch. 44), induce remission in 85% of people with AIH, but, when used alone, up to 50% of those treated will still have developed cirrhosis after 10 years.

Corticosteroids, usually prednisolone (Ch. 44), induce remission in 85% of people with AIH, but, when used alone, up to 50% of those treated will still have developed cirrhosis after 10 years.

Azathioprine (Ch. 38) has a corticosteroid-sparing action in AIH and is widely used in combination with corticosteroids, both to induce remission and for maintenance therapy. Treatment is usually required for up to 2 years.

Azathioprine (Ch. 38) has a corticosteroid-sparing action in AIH and is widely used in combination with corticosteroids, both to induce remission and for maintenance therapy. Treatment is usually required for up to 2 years.

Mycophenolate mofetil or possibly ciclosporin (Ch. 38) are used for AIH that has not responded to corticosteroids. Evidence for their effectiveness is limited.

Mycophenolate mofetil or possibly ciclosporin (Ch. 38) are used for AIH that has not responded to corticosteroids. Evidence for their effectiveness is limited.

Primary biliary cirrhosis

Treatment of PBC is less satisfactory because immunosuppression is ineffective. Ursodeoxycholic acid is the only drug licensed for use with PBC in the UK. This is a bile acid that is produced by bacterial oxidation of chenodeoxycholic acid. It retards progression of the disease possibly by reducing apoptosis of hepatocytes and suppression of the cytotoxic effects of other bile acids. The main unwanted effect is diarrhoea. About one-third of people treated will have a response, with reduction in elevated liver enzymes, and a reduced risk of either death or the need for liver transplantation.

Treatment of PBC is less satisfactory because immunosuppression is ineffective. Ursodeoxycholic acid is the only drug licensed for use with PBC in the UK. This is a bile acid that is produced by bacterial oxidation of chenodeoxycholic acid. It retards progression of the disease possibly by reducing apoptosis of hepatocytes and suppression of the cytotoxic effects of other bile acids. The main unwanted effect is diarrhoea. About one-third of people treated will have a response, with reduction in elevated liver enzymes, and a reduced risk of either death or the need for liver transplantation.

Supportive therapy is necessary to reduce the complications that can arise from malabsorption of fat-soluble vitamins. Vitamin D (Ch. 42) and calcium supplements should be given to reduce the risk of osteomalacia and osteoporosis.

Supportive therapy is necessary to reduce the complications that can arise from malabsorption of fat-soluble vitamins. Vitamin D (Ch. 42) and calcium supplements should be given to reduce the risk of osteomalacia and osteoporosis.

Treatment of pruritis with colestyramine (Ch. 48), which binds bile acids in the gut.

Treatment of pruritis with colestyramine (Ch. 48), which binds bile acids in the gut.

Chronic viral hepatitis

There are two important hepatic viral infections that can cause chronic hepatitis: hepatitis B virus (HBV; a DNA virus) and hepatitis C virus (HCV; an RNA virus). The result of the chronic inflammation produced by these viruses is cirrhosis.

Drugs for treatment of viral hepatitis

Mechanism of action and effects: Interferons are glycoprotein cytokines produced by virus-infected cells that protect uninfected cells of the same type. Interferon alfa binds to cell surface receptors and stimulates production of enzymes in the host cell that impair viral mRNA translation by host ribosomes. This inhibits viral replication and augments viral clearance from infected hepatocytes (Ch. 51). There are two forms of interferon alfa: interferon alfa-2a has lysine in position 23 and interferon alfa-2b has methionine in this position. Interferons are obtained either by recombinant DNA technology or from virus-stimulated leucocytes.

Pharmacokinetics: Interferon alfa is given by subcutaneous injection three times a week for 4–6 months. It is metabolised in the kidney and has a short half-life (3–4 h). Polyethylene glycol-conjugated (pegylated) derivatives of interferon alfa are available that increase the persistence of the interferon in the blood and these are given once weekly.

Nucleoside analogues

Mechanism of action and uses: Analogues of nucleosides and nucleotides (phosphorylated nucleosides) inhibit viral polymerase, reduce RNA and protein synthesis, and suppress viral replication (Ch. 51).

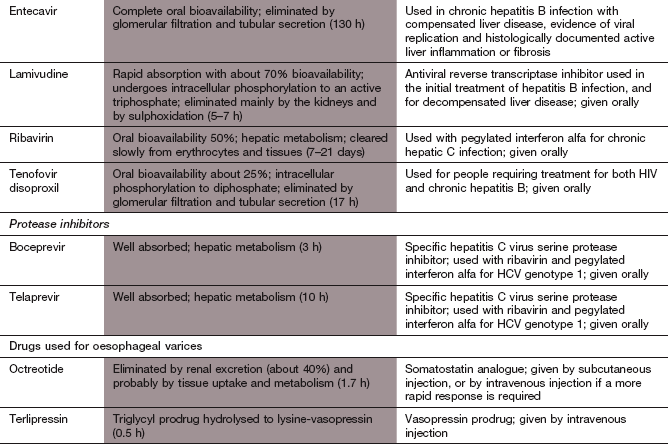

Entecavir is a guanosine nucleoside analogue.

Entecavir is a guanosine nucleoside analogue.

Lamivudine is a cytosine nucleoside analogue.

Lamivudine is a cytosine nucleoside analogue.

Ribavirin is a synthetic nucleoside analogue with activity against some RNA and DNA viruses. It inhibits viral RNA synthesis by blocking incorporation of uridine and cytidine. It also increases the production of antiviral cytokines. Ribavirin has little effect on viral replication when used alone, but it enhances the efficacy of interferon alfa against HCV. Ribavirin is also used by inhalation to treat respiratory syncytial virus infection.

Ribavirin is a synthetic nucleoside analogue with activity against some RNA and DNA viruses. It inhibits viral RNA synthesis by blocking incorporation of uridine and cytidine. It also increases the production of antiviral cytokines. Ribavirin has little effect on viral replication when used alone, but it enhances the efficacy of interferon alfa against HCV. Ribavirin is also used by inhalation to treat respiratory syncytial virus infection.

Tenofovir is a nucleotide analogue of adenosine 5′-monophosphate.

Tenofovir is a nucleotide analogue of adenosine 5′-monophosphate.

Pharmacokinetics: Nucleoside analogues are well absorbed from the gut. They are inactive prodrugs that are phosphorylated intracellularly to the active nucleotide derivatives, and then eliminated by the kidney. See Compendium at the end of the chapter for further details.

Protease inhibitors

Mechanism of action: Boceprevir and telaprevir are specific inhibitors of the HCV serine protease. The protease is responsible for the cleavage of viral polyprotein that is an essential process in viral replication. The protease may also aid the virus in evading the normal inflammatory response of the host cell, so protease inhibitors may enhance the host response to infection.

Resistance: Viral resistance is due to emergence of mutations that interfere with the ligand-binding site on the protease.

Pharmacokinetics: Boceprevir and telaprevir are well absorbed from the gut and are metabolized in the liver with half-lives of about 3 and 10 h respectively.

Nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, diarrhoea, altered taste.

Nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, diarrhoea, altered taste.

Rash is common, including Stevens–Johnson syndrome with telaprevir.

Rash is common, including Stevens–Johnson syndrome with telaprevir.

Paraesthesia, dizziness, headache, anxiety, depression, insomnia with boceprevir.

Paraesthesia, dizziness, headache, anxiety, depression, insomnia with boceprevir.

Drug interactions (Ch. 56): inhibition of the P450 enzyme CYP3A4 and P-glycoprotein by these drugs can lead to several potential drug interactions. Drugs that inhibit the activity of CYP3A4 can enhance the unwanted effects of protease inhibitors, whereas the concurrent use of inducers of CYP3A4 can lower plasma concentrations of the protease inhibitor and encourage viral resistance.

Drug interactions (Ch. 56): inhibition of the P450 enzyme CYP3A4 and P-glycoprotein by these drugs can lead to several potential drug interactions. Drugs that inhibit the activity of CYP3A4 can enhance the unwanted effects of protease inhibitors, whereas the concurrent use of inducers of CYP3A4 can lower plasma concentrations of the protease inhibitor and encourage viral resistance.

Management of chronic viral hepatitis

There is no role for drug treatment in acute hepatitis B, which usually resolves spontaneously. Chronic infection is characterised by persistence of hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) and other immunological markers at least 6 months after the acute infection. Antiviral treatment should be used if there is evidence of active chronic infection with ongoing liver damage and high viral replication (high titre of HBV DNA). This is usually, but not always, associated with hepatitis Be antigen (HBeAg) in plasma as a marker of active viral replication. The criteria for successful treatment are a matter of debate. Seroconversion to HBe antibody only occurs in a minority of those who are treated, and even fewer seroconvert to HBs antibody, which is the ideal outcome. Measurement of HBV DNA is a sensitive way to monitor treatment and detect drug resistance.

The optimal choice of antiviral treatment is contentious. Lamivudine has been advocated, but complete eradication of the virus by lamivudine is unusual, and the relapse rate on withdrawal is high, with only about 10% of people showing long-term responses once treatment is discontinued. Emergence of viral strains with drug resistance to lamivudine is common and occurs progressively, with a 15–30% prevalence of resistant strains after 1 year of treatment. Increasingly, entecavir or tenofovir are becoming first-choice antiviral drugs, either alone or with tenofovir given in combination with lamivudine. Viral resistance to entecavir or tenofovir is unusual.

Interferon alfa is now less commonly used. It achieves seroconversion in about one-third of cases, with no difference between the pegylated and non-pegylated forms of the drug. About 40% of those treated will show a conversion to low viral replication, and about 10% will have complete eradication. Relapse is frequent when treatment is stopped.

Chronic hepatitis C

The aim of treatment is eradication of the virus. If left untreated about 85% of people who are infected develop chronic infection and of these up to 30% will develop cirrhosis. Treatment with pegylated interferon alfa alone can eradicate the virus, with a 15% sustained response rate. It can also prevent liver damage even if eradication is not successful. Treatment duration and success depend on the viral strain, or genotype, of which three are found in Europe. The addition of ribavirin to pegylated interferon alfa increases the overall response rate to 45% for genotype 1 and 80% for genotypes 2 or 3, and the combination is standard therapy for all people who can tolerate both drugs. For genotypes 2 or 3, treatment for 24 weeks is sufficient for a maximal response, while treatment for genotype 1 (the most common type in developed countries) should be continued for 48 weeks in those who have a response in the first 24 weeks. Pegylated interferons produce up to a 10% higher response rate than the conventional interferons.

The addition of viral protease inhibitors such as boceprevir or telaprevir to the combination of interferon alfa and ribavirin is more effective than dual therapy in genotype 1 infection, but with a higher incidence of anaemia and other unwanted effects.

Chronic hepatic encephalopathy

Many chronic liver diseases predispose to the neuropsychiatric disturbance known as chronic hepatic encephalopathy. The clinical features are similar to those occurring in acute liver failure. Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis is a common cause of deterioration in previously compensated liver failure. In people with chronic encephalopathy nutritional support may be necessary, and malabsorption of fat-soluble vitamins can be a particular problem if there is cholestasis. Osteoporosis can result, made worse by the use of corticosteroids.

Management

Treatment of infections, constipation and electrolyte disturbances (particularly hypokalaemia), and avoidance of sedative drugs will help to prevent symptomatic encephalopathy.

Treatment of infections, constipation and electrolyte disturbances (particularly hypokalaemia), and avoidance of sedative drugs will help to prevent symptomatic encephalopathy.

Lactulose (Ch. 35) can be given orally to reduce colonic production of neurotoxins (particularly ammonia) by decreasing intestinal transit time and increasing nitrogen fixation by colonic bacteria. It may also reduce bacterial translocation form the colon and prevent episodes of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Lactulose is effective for both treatment and prevention of encephalopathy.

Lactulose (Ch. 35) can be given orally to reduce colonic production of neurotoxins (particularly ammonia) by decreasing intestinal transit time and increasing nitrogen fixation by colonic bacteria. It may also reduce bacterial translocation form the colon and prevent episodes of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Lactulose is effective for both treatment and prevention of encephalopathy.

Low-absorption oral antibacterials such as neomycin, metronidazole or rifaximin (Ch. 51) reduce bacterial ammonia production in the colon. They are usually used only for short periods. Neomycin is less favoured because of its potential to cause nephrotoxicity and ototoxicity, even though little is absorbed from the gut.

Low-absorption oral antibacterials such as neomycin, metronidazole or rifaximin (Ch. 51) reduce bacterial ammonia production in the colon. They are usually used only for short periods. Neomycin is less favoured because of its potential to cause nephrotoxicity and ototoxicity, even though little is absorbed from the gut.

Careful attention to nutrition is required, especially a balanced carbohydrate and protein intake. Branched-chain amino acids should be consumed in preference to aromatic amino acids.

Careful attention to nutrition is required, especially a balanced carbohydrate and protein intake. Branched-chain amino acids should be consumed in preference to aromatic amino acids.

Fat malabsorption can be treated with medium-chain triglyceride supplements, and sufficient calorie intake should be ensured. Supplements of fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, K) may be needed. Metabolic bone disease may require treatment with bisphosphonates (Ch. 42).

Fat malabsorption can be treated with medium-chain triglyceride supplements, and sufficient calorie intake should be ensured. Supplements of fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, K) may be needed. Metabolic bone disease may require treatment with bisphosphonates (Ch. 42).

Sepsis, including spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, is often due to bowel flora and should be treated with intravenous broad-spectrum antibacterial drugs, such as cefuroxime with metronidazole (Ch. 51).

Sepsis, including spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, is often due to bowel flora and should be treated with intravenous broad-spectrum antibacterial drugs, such as cefuroxime with metronidazole (Ch. 51).

Variceal haemorrhage

Varices are large collateral venous communications that develop in portal hypertension, most frequently at the gastro-oesophageal junction but also at other places such as the rectum. They arise from a combination of increased splanchnic blood flow and increased resistance to portal blood flow within the liver. Varices are found in 70% of people with cirrhosis and they carry a high risk of haemorrhage, from which mortality is 30–50%. Normal portal vein pressure is about 9 mmHg, while that in the inferior vena cava is 2–6 mmHg. The hepatic venous pressure gradient is therefore between 3 and 7 mmHg. Varices form when the venous pressure gradient rises above 10 mmHg. The probability of rupture is increased when the pressure gradient reaches 12 mmHg, and greatly increased when above 20 mmHg.

Management

Management of bleeding gastro-oesophageal varices

Repletion of blood volume can be carried out with colloid solution, or preferably with whole blood. Impaired coagulation and thrombocytopenia are common findings in advanced liver disease, and transfusion of platelet concentrates and fresh frozen plasma may be necessary.

Repletion of blood volume can be carried out with colloid solution, or preferably with whole blood. Impaired coagulation and thrombocytopenia are common findings in advanced liver disease, and transfusion of platelet concentrates and fresh frozen plasma may be necessary.

The risk of bacterial infections is high in acute variceal bleeding, and short-term antibacterial prophylaxis with an agent such as ciprofloxacin or ceftriaxone (Ch. 51) should be given.

The risk of bacterial infections is high in acute variceal bleeding, and short-term antibacterial prophylaxis with an agent such as ciprofloxacin or ceftriaxone (Ch. 51) should be given.

Endoscopic variceal band ligation or injection with a sclerosant is successful in up to 95% of cases. The main complications are oesophageal ulceration, increased risk of infections and pleural effusions.

Endoscopic variceal band ligation or injection with a sclerosant is successful in up to 95% of cases. The main complications are oesophageal ulceration, increased risk of infections and pleural effusions.

Endoscopic variceal injection of a cyanoacrylate tissue adhesive is effective for bleeding gastric varices, and is successful in 80% of cases. It is also an option for oesophageal varices. These compounds are tissue glues that polymerise on contact with water or blood.

Endoscopic variceal injection of a cyanoacrylate tissue adhesive is effective for bleeding gastric varices, and is successful in 80% of cases. It is also an option for oesophageal varices. These compounds are tissue glues that polymerise on contact with water or blood.

Balloon tamponade to compress the bleeding point achieves control in 80–90% of bleeding varices. It can be used to treat re-bleeding after endoscopic sclerosant therapy or as a holding measure, but is rarely used as a first-line treatment.

Balloon tamponade to compress the bleeding point achieves control in 80–90% of bleeding varices. It can be used to treat re-bleeding after endoscopic sclerosant therapy or as a holding measure, but is rarely used as a first-line treatment.

A transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) is used as rescue therapy in the 10–20% of cases when sclerosant therapy has failed.

A transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) is used as rescue therapy in the 10–20% of cases when sclerosant therapy has failed.

Terlipressin (N-triglycyl-8-lysine-vasopressin) is a prodrug that is slowly converted to lysine-vasopressin, a synthetic vasopressin analogue (Ch. 43). Given intravenously by bolus injection, it produces splanchnic vasoconstriction, reduces portal pressure and limits bleeding from varices. Unwanted effects are uncommon. It is mainly used when endoscopic sclerosant therapy is not immediately available. Vasopressin has been used to treat bleeding varices, but has a shorter duration of action than terlipressin and must be given by intravenous infusion. Systemic vasoconstriction causes ischaemic complications in up to 50% of those treated with vasopressin which is therefore little used.

Terlipressin (N-triglycyl-8-lysine-vasopressin) is a prodrug that is slowly converted to lysine-vasopressin, a synthetic vasopressin analogue (Ch. 43). Given intravenously by bolus injection, it produces splanchnic vasoconstriction, reduces portal pressure and limits bleeding from varices. Unwanted effects are uncommon. It is mainly used when endoscopic sclerosant therapy is not immediately available. Vasopressin has been used to treat bleeding varices, but has a shorter duration of action than terlipressin and must be given by intravenous infusion. Systemic vasoconstriction causes ischaemic complications in up to 50% of those treated with vasopressin which is therefore little used.

Octreotide (Ch. 43) and somatostatin (Ch. 43) are probably as effective as vasopressin for stopping haemorrhage, but there is less convincing evidence compared with terlipressin. They also work by reducing portal venous pressure.

Octreotide (Ch. 43) and somatostatin (Ch. 43) are probably as effective as vasopressin for stopping haemorrhage, but there is less convincing evidence compared with terlipressin. They also work by reducing portal venous pressure.

Prevention of variceal re-bleeding

Splanchnic vasoconstrictors that lower portal flow and reduce portal pressure by at least 20% will reduce the risk of re-bleeding to about 10% at 2 years. This is most often achieved by the use of a non-selective β-adrenoceptor antagonist such as propranolol (Ch. 5). Sometimes, isosorbide mononitrate (Ch. 5) is added to vasodilate the portal circulation and further reduce portal flow. However, this can produce systemic hypotension and promote renal salt and water retention.

Splanchnic vasoconstrictors that lower portal flow and reduce portal pressure by at least 20% will reduce the risk of re-bleeding to about 10% at 2 years. This is most often achieved by the use of a non-selective β-adrenoceptor antagonist such as propranolol (Ch. 5). Sometimes, isosorbide mononitrate (Ch. 5) is added to vasodilate the portal circulation and further reduce portal flow. However, this can produce systemic hypotension and promote renal salt and water retention.

Local treatment of the varices, for example by endoscopic band ligation, will reduce the risk of re-bleeding, but does not reduce portal pressure. In about 50% of cases, the varices will recur within 2 years. Banding should therefore be followed by drug therapy to lower portal pressure.

Local treatment of the varices, for example by endoscopic band ligation, will reduce the risk of re-bleeding, but does not reduce portal pressure. In about 50% of cases, the varices will recur within 2 years. Banding should therefore be followed by drug therapy to lower portal pressure.

A TIPS is most commonly used when re-bleeding follows endoscopic variceal ligation and drug therapy to lower portal pressure. It can lead to chronic encephalopathy and other significant adverse effects. Surgical creation of a portosystemic shunt is an alternative to TIPS.

A TIPS is most commonly used when re-bleeding follows endoscopic variceal ligation and drug therapy to lower portal pressure. It can lead to chronic encephalopathy and other significant adverse effects. Surgical creation of a portosystemic shunt is an alternative to TIPS.

Ascites

Ascites in chronic liver disease arises largely as a result of splanchnic vasodilation. Portal hypertension results in local production of vasodilators, which reduce effective circulating blood volume. This promotes salt and water retention in the kidney due to activation of the renin–angiotensin system. The increased portal pressure combined with vasodilation leads to transudation of fluid into the peritoneal cavity. Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis can complicate ascites associated with liver disease and make the ascites resistant to treatment.

Management

The presence of ascites in chronic liver disease is associated with a poor prognosis, with a 5-year survival of 30–40%, unless liver transplantation is carried out. Management of ascites includes:

diuretic therapy, starting with a potassium-sparing diuretic such as spironolactone (Ch. 14) together with a low dose of furosemide, with care taken to avoid hypovolaemia and consequent pre-renal failure,

diuretic therapy, starting with a potassium-sparing diuretic such as spironolactone (Ch. 14) together with a low dose of furosemide, with care taken to avoid hypovolaemia and consequent pre-renal failure,

drainage by paracentesis is usually required in large-volume ascites in addition to diuretics as maintenance therapy; paracentesis should be accompanied by plasma expansion with intravenous albumin to maintain circulating blood volume. Refractory ascites that fails to respond to high doses of diuretics or recurs rapidly after paracentesis may need repeated large-volume paracentesis with intravenous albumin replacement,

drainage by paracentesis is usually required in large-volume ascites in addition to diuretics as maintenance therapy; paracentesis should be accompanied by plasma expansion with intravenous albumin to maintain circulating blood volume. Refractory ascites that fails to respond to high doses of diuretics or recurs rapidly after paracentesis may need repeated large-volume paracentesis with intravenous albumin replacement,

a TIPS can be used to lower portal pressure for refractory ascites.

a TIPS can be used to lower portal pressure for refractory ascites.

One-best-answer (OBA) questions

1. Identify the inaccurate statement below concerning antiviral treatments.

A Interferon alfa protects against viral hepatitis.

B Pegylated and non-pegylated versions of interferon alfa are cleared from the plasma at the same rate.

C Boceprevir is an inhibitor of hepatitis C virus (HCV) serine protease.

E Combination therapy with ribavirin and interferon alfa is recommended for the treatment of hepatitis C.

2. A 45-year-old woman was admitted to the accident and emergency department with acute liver failure. Identify the inaccurate statement below concerning her condition.

A Paracetamol overdose should be excluded.

B Paracetamol-induced hepatocellular liver damage is not reversible.

C Mannitol could be used to reduce the cerebral oedema associated with acute liver failure.

D Warfarin could be used to manage coagulopathy.

E Terlipressin could be given as a vasoconstrictor to treat shock.

Case-based questions

Mr SA was a 61-year-old publican who presented ‘feeling as though I am 9 months pregnant’. His abdominal swelling was caused by ascites, which was drained. A liver biopsy was performed, which showed micro-nodular cirrhosis. He commenced treatment with oral spironolactone.

A Was this a good choice of diuretic?

He remained well on this regimen for 5 years but continued to imbibe large quantities of alcohol. He re-presented as an emergency, having had a haematemesis and melaena. At the time he was slightly jaundiced and demonstrated signs of hepatic encephalopathy. In addition, there was gynaecomastia and testicular atrophy. The liver edge was palpable 8 cm below the right costal margin. Investigations showed a bilirubin level of 27 mmol⋅L−1 (normal <17 mmol⋅L−1) and albumin of 30 g⋅L−1 (normal 32–50 g⋅L−1). A gastroscopy was performed under sedation with intravenous diazepam and revealed oesophageal varices.

B What evidence was there to indicate diminished hepatic reserve in this man?

C Was diazepam a good choice during gastroscopy?

D It has been shown that the incidence of re-bleeding from oesophageal varices can be reduced by oral propranolol (by reducing portal venous pressure).

What effect is this man's liver disease likely to have on the pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics of propranolol?

E People with hepatic cirrhosis are often treated with colestyramine and/or lactulose. How do these drugs work and what benefits are produced?

F What would you use for pain relief in someone with established liver cirrhosis?

1. Answer B is the inaccurate statement.

A True. Interferon alfa prevents virus replication (Ch. 52) and can augment immune responses.

B False. Interferon alfa conjugated with polyethylene glycol (pegylated interferon alfa) has a longer plasma half-life (about 80 h) than the non-conjugated form (3–4 h).

C True. Boceprevir and telaprevir inhibit HCV serine protease and reduce viral replication.

D True. Lamivudine is converted to its active triphosphate form by phosphorylation by viral enzymes.

E True. Combined ribavirin and interferon alfa are recommended for the treatment of hepatitis C, giving better results than either treatment alone.

2. Answer D is the inaccurate statement.

A True. Paracetamol poisoning is the most common cause of acute liver failure in the UK.

B True. Liver damage induced by paracetamol is irreversible.

C True. Mannitol is an osmotic diuretic with relatively few uses (Ch. 14), but is effective for the reduction of cerebral oedema.

D False. The coagulopathy is due to a reduction in vitamin K-dependent clotting factors. Warfarin, a vitamin K antagonist, would make the problem worse, and vitamin K should be given.

E True. Terlipressin, an analogue of vasopressin that causes vasoconstriction, can be given to treat shock.

Case-based answers

A Mr SA is at risk of encephalopathy/coma from electrolyte imbalances. Spironolactone, a potassium-sparing diuretic, would avoid changes in serum K+ such as might be caused by loop diuretics or thiazides; these diuretics could be given cautiously after a few days. There is an increase in circulating aldosterone probably contributing to fluid retention, so spironolactone is usually chosen.

B Diminished hepatic reserve is indicated by (i) increased plasma bilirubin, which will be a combination of unconjugated bilirubin, because of impaired glucuronidation, plus conjugated bilirubin, because of impaired biliary excretion; (ii) decreased plasma albumin, caused by decreased synthesis, which will lower the osmotic pressure of blood and lead to oedema/ascites; (iii) decreased clotting factors, caused by decreased synthesis, which may contribute to oesophageal bleeding; (iv) increased oestrogenic activity, as evidenced by gynaecomastia and testicular atrophy, possibly caused by decreased sex steroid inactivation in the liver.

C Reduced hepatic cytochrome P450 metabolism might cause increased plasma levels of diazepam, a long-acting benzodiazepine. A shorter-acting benzodiazepine without active metabolites, such as midazolam, would be a better choice.

D Reduced plasma protein concentration means that less propranolol is bound and free drug is increased. This will result in an increased response. Reduced hepatic P450 activity will decrease first-pass metabolism of propranolol and increase its bioavailability, while reduced clearance will increase its elimination half-life.

E In liver cirrhosis, decreased bile outflow leads to accumulation of bile salts in the blood and their deposition in the skin, which causes itching. Colestyramine, an anion-exchange resin, adsorbs bile salts within the gut and reduces their enterohepatic circulation. Lactulose is a laxative (Ch. 35) and its fermentation products in the lower gastrointestinal tract reduce microbial formation of ammonia and tyramine, which may otherwise contribute to encephalopathy.

F Analgesia in cirrhosis can be difficult. Opioids should usually be avoided because of the risk of encephalopathy, but low doses could be given. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are best avoided to reduce the risk of haemorrhage from oesophageal varices. Paracetamol is potentially hepatotoxic, but it is well tolerated in cirrhosis, probably because decreased perfusion of hepatocytes and reduced activity of cytochrome P450 outweigh the impaired inactivation by conjugation.

Bernal, W, Auzinger, A, Dhawan, A, et al. Acute liver failure. Lancet. 2010;376:190–201.

Chapman, R, Fevery, J, Kalloo, A, et al. Diagnosis and management of primary sclerosing cholangitis. Hepatology. 2010;51:660–678.

Cooke, GS, Main, J, Thursz, MR. Treatment for hepatitis B. BMJ. 2009;339:b5429.

Dienstag, JL. Drug therapy: hepatitis B virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1486–1500.

Garcia-Tsao, G, Bosch, J. Management of varices and variceal hemorrhage in cirrhosis. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:823–832.

Krawitt, EL. Autoimmune hepatitis. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:54–66.

Liaw, Y-F, Chu, GM. Hepatitis B virus infection. Lancet. 2009;373:582–592.

Manns, MP, Czaja, AJ, Gorham, JD, et al. Diagnosis and management of autoimmune hepatitis. Hepatology. 2010;51:1–31.

Nash, KL, Bentley, I, Hirschfield, GM. Managing hepatitis C virus infection. BMJ. 2009;338:b2366.

Rosen, HR. Chronic hepatitis C infection. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2429–2438.

Rowe, IA, Mutimer, DJ. Protease inhibitors for treatment of genotype 1 hepatitis C virus infection. BMJ. 2011;343:d6972.

Runyon, BA. Management of adult patients with ascites due to cirrhosis: an update. Hepatology. 2009;49:2087–2105.

Schuppan, D, Afdhal, NH. Liver cirrhosis. Lancet. 2008;371:838–851.

Selmi, C, Bowlus, CL, Gershwin, ME, et al. Primary biliary cirrhosis. Lancet. 2011;377:1600–1609.

Shah, VH, Kamath, P. Management of portal hypertension. Postgrad Med. 2006;119:14–18.