Skin disorders

Vehicles for topical skin applications

Topical preparations for the treatment of skin disorders usually have two components: a vehicle or base, and the active ingredient such as a corticosteroid or an antifungal agent. Five types of base are used:

ointments, which are greases such as white or yellow soft paraffin. They are more occlusive on the skin than creams, and this keeps the skin hydrated,

ointments, which are greases such as white or yellow soft paraffin. They are more occlusive on the skin than creams, and this keeps the skin hydrated,

pastes, which are suspensions of fine powder in an ointment and will stay where they are placed on the skin. Their main use is to apply noxious chemicals that should be confined to one area of the skin,

pastes, which are suspensions of fine powder in an ointment and will stay where they are placed on the skin. Their main use is to apply noxious chemicals that should be confined to one area of the skin,

creams, which are emulsions of water with a grease. They are less greasy than ointments, are absorbed more quickly into the skin and are often used as a vehicle for active ingredients,

creams, which are emulsions of water with a grease. They are less greasy than ointments, are absorbed more quickly into the skin and are often used as a vehicle for active ingredients,

lotions, which are any kind of liquid. They are less messy for use on wet surfaces and hairy areas and their main advantage is a cooling effect,

lotions, which are any kind of liquid. They are less messy for use on wet surfaces and hairy areas and their main advantage is a cooling effect,

gels, which can be hydrophilic or hydrophobic and have a high water content. They are combined with an active ingredient, particularly for use on the face or scalp.

gels, which can be hydrophilic or hydrophobic and have a high water content. They are combined with an active ingredient, particularly for use on the face or scalp.

Atopic and contact dermatitis

Dermatitis is a term used to describe eczematous inflammation of the skin. It has significant underlying genetic influences, but is triggered by external factors.

Atopic dermatitis (eczema)

The pathogenesis of atopic dermatitis is determined by a combination of genetic, environmental, pharmacological and immunological factors. There are two forms of atopic dermatitis. The extrinsic type (70–80% of cases) is associated with a food or aero-allergen. There is an association with other atopic disorders such as asthma and hay fever. It is associated with IgE-mediated sensitisation, with eosinophilia in the peripheral blood and with a raised plasma IgE concentration. In atopic individuals, circulating mononuclear cells have a reduced ability to produce interferon γ, which normally inhibits both IgE production and the proliferation of T-helper type 2 (Th2) lymphocytes. The function of regulatory T-cells is also abnormal. Keratinocytes produce cytokines that stimulate eosinophil activation and adhesion to vascular walls. The intrinsic form of atopic dermatitis also involves immune dysregulation, but there is no IgE excess or eosinophilia.

As a result of the changes in immune regulation in atopic individuals, Th2-cells proliferate. Dominance of either a Th1 or Th2 response is partially programmed in early life, with exposure to microbial antigens promoting the normal Th1 dominance. Th1-cell responses are induced by infections, and suppress the development of Th2-cells. It is possible that the increasing use of antibacterial drugs in childhood may partially explain the rise in atopic dermatitis (Chs 38 and 39).

Affected skin is red, scaly and extremely dry, often affecting the flexures. The dryness is a consequence of the inflammation, but the permeability barrier function of the skin is also impaired, resulting in increased transepidermal water loss. There may be vesicles and weeping with crusting over the skin surface. Scratching produces excoriation and thickening of the skin. The affected skin is infiltrated with activated T-cells, with selective recruitment of Th2-cells, and eosinophils. Increased carriage of Staphylococcus aureus on the affected skin may also maintain inflammation by activating T-cells and macrophages.

Contact dermatitis

an external agent producing direct irritation,

an external agent producing direct irritation,

immunological sensitisation involving a delayed hypersensitivity response (Ch. 39). Once the skin has been sensitised, the potential for further reaction persists indefinitely. Sensitisation can arise in response to topical application of drugs.

immunological sensitisation involving a delayed hypersensitivity response (Ch. 39). Once the skin has been sensitised, the potential for further reaction persists indefinitely. Sensitisation can arise in response to topical application of drugs.

Other types of dermatitis

These include nummular (discoid) eczema, photosensitive dermatitis and seborrhoeic dermatitis.

Treatment of atopic dermatitis

Emollients (substances that soften the skin) are helpful as hydrophobic agents that seal the surface of the skin and reduce water loss. Paraffin derivatives are most effective but are greasy and not well accepted by most people. Alternatives, such as aqueous creams, are more cosmetically acceptable.

Emollients (substances that soften the skin) are helpful as hydrophobic agents that seal the surface of the skin and reduce water loss. Paraffin derivatives are most effective but are greasy and not well accepted by most people. Alternatives, such as aqueous creams, are more cosmetically acceptable.

Avoidance of irritants, such as soaps, detergents, alcohols and astringents. Wet dressings may help to prevent skin fissuring and reduce scratching.

Avoidance of irritants, such as soaps, detergents, alcohols and astringents. Wet dressings may help to prevent skin fissuring and reduce scratching.

Identification of allergens by patch tests and their subsequent elimination.

Identification of allergens by patch tests and their subsequent elimination.

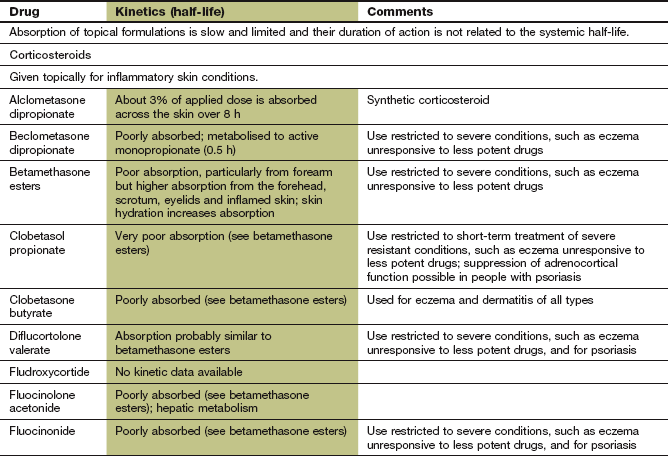

Topical corticosteroid ointment (Ch. 44) is effective, but a low-potency corticosteroid should be chosen if there is continuous use, to minimise unwanted effects. The anti-inflammatory effect of these drugs makes them the mainstay of treatment, but diminished effectiveness with prolonged use (tachyphylaxis) limits their long-term value. Tachyphylaxis may be delayed by twice-weekly application of a more potent corticosteroid.

Topical corticosteroid ointment (Ch. 44) is effective, but a low-potency corticosteroid should be chosen if there is continuous use, to minimise unwanted effects. The anti-inflammatory effect of these drugs makes them the mainstay of treatment, but diminished effectiveness with prolonged use (tachyphylaxis) limits their long-term value. Tachyphylaxis may be delayed by twice-weekly application of a more potent corticosteroid.

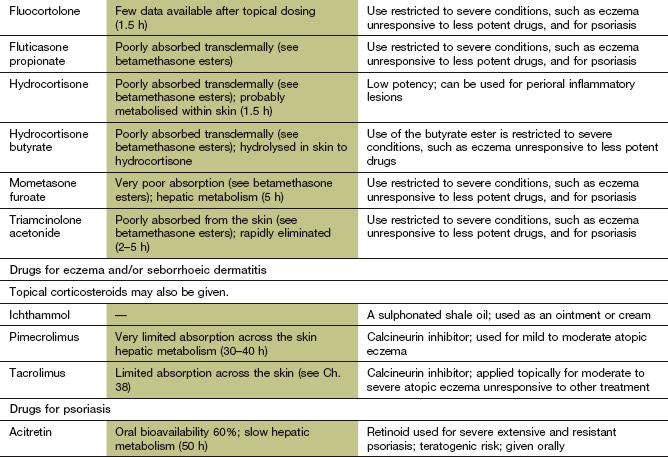

Topical calcineurin inhibitors, such as tacrolimus (Ch. 38), directly or indirectly reduce activation of many of the inflammatory cells involved in the pathogenesis of the dermatitic lesions, including T-cells, dendritic cells, mast cells and keratinocytes. Local burning is the major unwanted effect, and skin malignancy has been reported. Tacrolimus is more effective than a potent corticosteroid for moderate to severe eczema.

Topical calcineurin inhibitors, such as tacrolimus (Ch. 38), directly or indirectly reduce activation of many of the inflammatory cells involved in the pathogenesis of the dermatitic lesions, including T-cells, dendritic cells, mast cells and keratinocytes. Local burning is the major unwanted effect, and skin malignancy has been reported. Tacrolimus is more effective than a potent corticosteroid for moderate to severe eczema.

Sedative antihistamines (Ch. 39) at night assist sleep, although they have little effect on itching. A topical formulation of the tricyclic antidepressant doxepin (see Ch. 22) is available to treat itch. It is uncertain whether its antihistamine activity is the major mode of action.

Sedative antihistamines (Ch. 39) at night assist sleep, although they have little effect on itching. A topical formulation of the tricyclic antidepressant doxepin (see Ch. 22) is available to treat itch. It is uncertain whether its antihistamine activity is the major mode of action.

Immunosuppressant therapy with azathioprine, ciclosporin or mycophenolate mofetil (Ch. 38) can be tried for treatment-resistant dermatitis. Apart from unwanted effects the main problem is rapid relapse when treatment is stopped.

Immunosuppressant therapy with azathioprine, ciclosporin or mycophenolate mofetil (Ch. 38) can be tried for treatment-resistant dermatitis. Apart from unwanted effects the main problem is rapid relapse when treatment is stopped.

Phototherapy with natural sunlight is helpful, but sweating can increase pruritus. Narrow-band ultraviolet B (UVB) radiation is a useful alternative.

Phototherapy with natural sunlight is helpful, but sweating can increase pruritus. Narrow-band ultraviolet B (UVB) radiation is a useful alternative.

Tar bandages on the limbs are messy, but have anti-inflammatory and anti-pruritic effects.

Tar bandages on the limbs are messy, but have anti-inflammatory and anti-pruritic effects.

Systemic antibacterial drugs are given for secondary infection. Anti-staphylococcal agents are often helpful if the skin lesions are poorly controlled.

Systemic antibacterial drugs are given for secondary infection. Anti-staphylococcal agents are often helpful if the skin lesions are poorly controlled.

Treatment of contact dermatitis

Provision of a barrier to an irritant; for example wearing gloves or removing an allergen may be sufficient.

Provision of a barrier to an irritant; for example wearing gloves or removing an allergen may be sufficient.

Dilute topical corticosteroid ointment (Ch. 44).

Dilute topical corticosteroid ointment (Ch. 44).

Potassium permanganate soaks can help to dry up exudative lesions.

Potassium permanganate soaks can help to dry up exudative lesions.

Psoriasis

Psoriatic skin lesions are produced by a very rapid proliferation of epidermal cells. Cell turnover time is decreased from about 28 days to 3–4 days, which prevents adequate maturation. Instead of producing a normal keratinous surface layer, the skin thickens, forming a silvery scale with dilated upper dermal blood vessels. Psoriatic plaques (psoriasis vulgaris, accounting for 90% of cases) are usually found on the elbows, knees, lower back, buttocks and scalp. Various subtypes of psoriasis present with different clinical manifestations. An inflammatory arthritis occurs in up to 25% of people with psoriasis (see Ch. 30).

There is a genetic component to psoriasis, which interacts with unknown environmental factors to produce an immune reaction in the dermis. Antigen-presenting cells in the dermis mature after contact with the antigen, migrate to regional lymph nodes and activate T-cells. T-cells then proliferate and enter the circulation and extravasate into the skin at sites of inflammation, assisted by local chemokine production. In the dermis, interaction with the initiating antigen results in Th1 immune responses, with secretion of cytokines such as interferon γ, interleukin (IL)-12 and IL-23 and tumour necrosis factor α (TNFα). The cytokines stimulate cell proliferation and impair maturation of keratinocytes, and produce vascular changes in the skin.

Psoriasis can be provoked or exacerbated by several drugs, including lithium, chloroquine, hydroxychloroquine, β-adrenoceptor antagonists, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors.

There are several treatments for the skin lesions, both topical and systemic, but none produce long-term remission. Increasingly, combinations of treatments have been found to be more effective than one agent alone.

Topical therapy

These reduce scaling and itching and may be sufficient in mild psoriasis (see atopic dermatitis, above). They can also be used with a keratolytic.

Keratolytics

Keratolytics such as salicylic acid break down keratin and soften skin, which improves penetration of other treatments. Salicylic acid ointment is most frequently used.

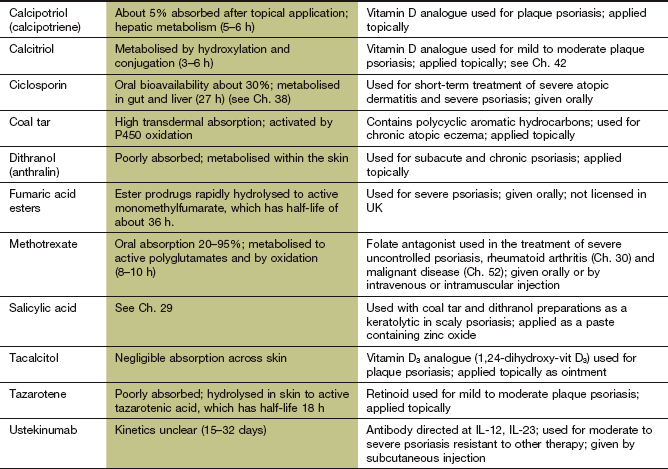

Vitamin D analogues

Vitamin D regulates epidermal proliferation and differentiation. It also has immunosuppressant properties. Vitamin D analogues (e.g. calcipotriol, calcitriol) are clean and simple to apply and are particularly useful for chronic plaque psoriasis, although complete clearing of the plaques is unusual. Ointment has a greater emollient effect than has cream, but is messy to apply. Calcipotriol should not usually be used on the face, where it often causes irritation; calcitriol may be better tolerated on this site, although it is less effective elsewhere. Excessive use of vitamin D analogues can lead to hypercalcaemia, but this is not a problem at recommended dosages. The ease of use of these compounds makes them a popular choice if a keratolytic is insufficient.

Topical retinoids

Retinoids are discussed more fully under systemic treatments. Tazarotene gel can be applied to plaque psoriasis and has minimal systemic absorption. Unlike other retinoids, tazarotene is selective for retinoic acid receptor (RAR) proteins, with no affinity for retinoid X receptors (RXR) (see below). This may reduce unwanted effects, which are mainly local irritation of healthy skin with pruritus. Tazarotene should be avoided for 1 month before conception, because of potential teratogenic effects.

Dithranol

This anthraquinone decreases cell division and is effective for healing psoriatic plaques. In hospital it is applied in a stiff paste to the plaque so that the dithranol does not burn normal skin, and is left in contact with the plaque for 24 h. At home, dithranol is used as a cream that is applied to the plaque for 30 min and then washed off. The oxidation products of dithranol stain the skin brown, leaving discoloration of healed areas for a few days. They also stain clothes and bedding a mauve colour that will not wash out. Since dithranol irritates normal skin, it should not be used in flexures.

Coal tar preparations

Crude coal tar is a mixture of a large number of hydrocarbons that have a cytostatic action. It enhances the healing effect of UVB radiation on psoriatic lesions. The main disadvantage is messiness, and its efficacy when used alone is modest. More refined tar preparations have greater acceptability, but are even less effective.

Phototherapy

Ultraviolet light produces improvement by inhibiting DNA synthesis and depleting intra-epidermal T-cells. It should not be used on individuals with very fair skin who burn in the sun. Broad-band UVB (‘sunburn’ wavelength 270–350 nm) has largely been replaced by the more effective narrow-band UVB (311–313 nm). Long-wavelength UVA (320–400 nm) requires more specialised equipment and prior administration of an oral psoralen as a photosensitising drug (a process called photochemotherapy or PUVA therapy). Psoralen probably intercalates between pyrimidine base pairs in the DNA helix and inhibits cell replication. PUVA is usually reserved for severe, resistant psoriasis and is more effective than treatment with UVB. Psoralen can produce nausea and headache acutely. The long-term risks of PUVA include accelerated skin ageing and an increased incidence of skin cancer, and systemic treatments are increasingly preferred.

Topical corticosteroid preparations

These should be used sparingly on limited areas, since unwanted effects can be troublesome (Ch. 44). Withdrawal of a high-potency corticosteroid can produce a rebound exacerbation and even generalised pustular psoriasis.

Systemic treatments

Apart from emollients and corticosteroids, which are most useful for chronic plaque psoriasis, topical treatments should be avoided in more inflammatory forms of the condition because they can cause troublesome skin irritation. Systemic treatment is used for the more severe forms of disease.

Methotrexate

This is a very effective treatment at low dosages for resistant and widespread psoriasis. Its main actions are cytostatic and immunosuppressant (see Chs 38 and 52). Oral or intramuscular dosing is commonly used once a week. Bone marrow depression and hepatotoxicity with liver fibrosis are the main complications; blood counts and serum procollagen III, to identify liver toxicity, must be checked every 3 months.

Retinoids

This term covers vitamin A (retinol) and therapeutically useful synthetic vitamin A derivatives, such as acitretin, the active metabolite of etretinate (which is no longer used). Given orally, they are anti-inflammatory and cytostatic. Vitamin A, and its metabolites all-trans-retinoic acid and 9-cis-retinoic acid, are involved in epithelial cell growth and differentiation. Retinoids enter cells by endocytosis and interact with two forms of retinoic acid nuclear receptor, retinoic acid receptors (RARs) and retinoid X receptors (RXRs), which are related to steroid/thyroid hormone receptors (Ch. 1). The retinoid–receptor complex initiates gene transcription and may affect cell growth and differentiation by modulation of growth factors and their receptors. Response of psoriatic lesions is delayed by up to 2 months. Elimination of retinoids is by hepatic metabolism. Unwanted effects are almost universal and include dry lips and nasal mucosa, dryness of the skin with localised peeling over the digits, and transient thinning of hair. These effects are dose-dependent and reversible. Longer-term problems include ossification of ligaments, increased plasma triglycerides and, to a lesser extent, increased plasma cholesterol. There is a high risk of teratogenesis and women must use adequate contraception during treatment, and stop treatment for 3 years before conception.

Ciclosporin or tacrolimus

These immunosuppressants (Ch. 38) are effective in psoriasis at lower doses than those required for prevention of allograft rejection. However, remissions induced by these drugs are usually short-lived.

Biologic agents

Etanercept, infliximab and adalimumab (Chs 30 and 34) are intravenous therapies that block TNFα and are highly effective in treatment-resistant psoriasis. They inhibit the production of chemokines and endothelial adhesion molecules that attract activated lymphocytes into the skin. Infliximab produces a more rapid response than etanercept. Ustekinumab, an inhibitor of IL-12 and IL-23, is effective for plaque psoriasis that has not responded to at least two standard systemic therapies. IL-12 and IL-23 are products of dendritic cells and macrophages which activate T-cells involved in the inflammatory response in psoriasis.

Fumaric acid esters

This is an oral unlicensed treatment for severe psoriasis that probably works by promoting a Th2-cell response in place of the Th1-dominant response found in psoriasis. This results from inhibition of nuclear factor κB (NF-κB), enhancing T-cell apoptosis. Fumaric acid is poorly absorbed from the gut and is therefore given as an ester that is rapidly hydrolysed to monomethylfumarate, the active compound. Unwanted effects include gastrointestinal upset in more than two-thirds of people, and flushing in one-third.

Acne

Acne most commonly arises in adolescence and often regresses in the late teens or early twenties. Acne affects areas of skin with large numbers of sebaceous glands, especially the face, back and chest. There is increased production of sebum, which distends the pilosebaceous duct, producing a small closed papule (comedo) called a whitehead. Hyperkeratosis at the mouth of the hair follicle blocks the duct. If the duct then opens, compacted follicular cells at the tip give comedones the appearance of a blackhead. A resident anaerobic bacterium, Propionibacterium acnes, degrades triglycerides in sebum to free fatty acids and glycerol. It also produces chemotactic factors and inflammatory mediators. These mediators together with the irritant free fatty acids produce inflamed lesions of pustules and nodules, which can coalesce to form multilocular cysts. The inflammatory lesions can scar, leaving permanent disfigurement.

Acne has a genetic background, which determines the rate of sebum production, particularly in response to androgens. Androgens are produced at puberty and induce hypertrophy of sebaceous glands, and the excess secretion rate in predisposed individuals triggers the acne. Acne can also be produced by systemic corticosteroids or anabolic steroids (Ch. 46). In women, it can be a manifestation of polycystic ovary syndrome (Ch. 43).

Treatment of acne

There are several effective treatments for acne. The choice will depend on the nature of the lesions and their severity. Topical treatments do not influence the rate of production of sebum.

Topical treatments

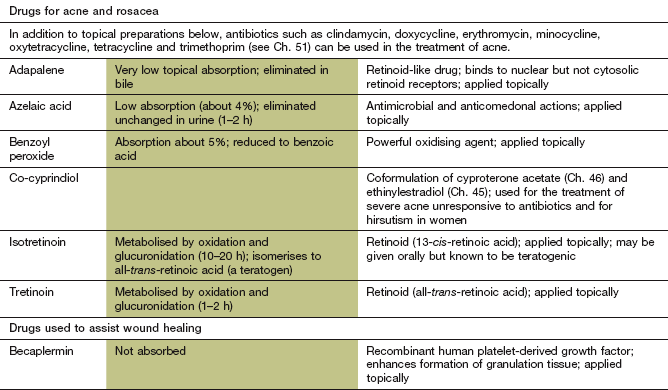

Benzoyl peroxide has antibacterial activity against P. acnes and a keratolytic action, both of which reduce the numbers of comedones. It produces scaling and skin irritation, which may limit its use to short treatment periods.

Benzoyl peroxide has antibacterial activity against P. acnes and a keratolytic action, both of which reduce the numbers of comedones. It produces scaling and skin irritation, which may limit its use to short treatment periods.

Topical antibacterials, for example clindamycin and erythromycin (Ch. 51), are less effective than oral antibacterials but have fewer unwanted effects. Their efficacy is similar to that of benzoyl peroxide, but they produce less skin irritation. Combination therapy with benzoyl peroxide reduces the problem of bacterial resistance. Topical antibacterials are used for mild to moderate acne, and are particularly useful in pregnant women since there is no systemic absorption.

Topical antibacterials, for example clindamycin and erythromycin (Ch. 51), are less effective than oral antibacterials but have fewer unwanted effects. Their efficacy is similar to that of benzoyl peroxide, but they produce less skin irritation. Combination therapy with benzoyl peroxide reduces the problem of bacterial resistance. Topical antibacterials are used for mild to moderate acne, and are particularly useful in pregnant women since there is no systemic absorption.

Isotretinoin (13-cis-retinoic acid) is a vitamin A derivative with a keratolytic action that unblocks the pilosebaceous follicles and allows flow of sebum to extrude the plug. The mechanism of action within the cell is similar to that of acitretin (see under psoriasis). It also reduces sebum production by up to 90% by decreasing sebocyte proliferation; this action is probably independent of effects on nuclear retinoid receptors. Topically, isotretinoin produces erythema and scaling, which can be minimised by starting with a low concentration. Adapalene is an extensively modified retinoid that has a faster onset of action and produces less skin irritation.

Isotretinoin (13-cis-retinoic acid) is a vitamin A derivative with a keratolytic action that unblocks the pilosebaceous follicles and allows flow of sebum to extrude the plug. The mechanism of action within the cell is similar to that of acitretin (see under psoriasis). It also reduces sebum production by up to 90% by decreasing sebocyte proliferation; this action is probably independent of effects on nuclear retinoid receptors. Topically, isotretinoin produces erythema and scaling, which can be minimised by starting with a low concentration. Adapalene is an extensively modified retinoid that has a faster onset of action and produces less skin irritation.

Azelaic acid is an aliphatic dicarboxylic acid that has an antibacterial action against propionibacteria and is effective against bacteria that have become resistant to erythromycin and tetracycline. It also inhibits the division of keratinocytes, which may reduce follicular plugging and prevent the development of comedones. The most frequent unwanted effects are local burning, scaling or itching, although hypopigmentation can also be a problem. Azelaic acid is most effective for mild to moderate non-inflammatory comedonal acne, especially of the face.

Azelaic acid is an aliphatic dicarboxylic acid that has an antibacterial action against propionibacteria and is effective against bacteria that have become resistant to erythromycin and tetracycline. It also inhibits the division of keratinocytes, which may reduce follicular plugging and prevent the development of comedones. The most frequent unwanted effects are local burning, scaling or itching, although hypopigmentation can also be a problem. Azelaic acid is most effective for mild to moderate non-inflammatory comedonal acne, especially of the face.

Nicotinamide gel has equivalent efficacy to topical antibacterials. It has an anti-inflammatory action by inhibiting production of lipids in sebaceous secretions (Ch. 48). Unwanted effects include dryness, pruritus and burning of the skin.

Nicotinamide gel has equivalent efficacy to topical antibacterials. It has an anti-inflammatory action by inhibiting production of lipids in sebaceous secretions (Ch. 48). Unwanted effects include dryness, pruritus and burning of the skin.

Systemic treatments

Oral antibacterials that are active against P. acnes are used for inflammatory acne (papules/pustules). Penetration into sebaceous follicles is poor, but they produce some improvement after 2–3 months, requiring 4–6 months of treatment for maximal benefit. Treatment should be given for extended periods, since relapse is common if it is stopped. Among the more useful antibacterial agents are tetracyclines, for example oxytetracycline and doxycycline. Alternatives include ciprofloxacin and trimethoprim (Ch. 51). Widespread resistance to erythromycin makes it a less suitable choice.

Oral antibacterials that are active against P. acnes are used for inflammatory acne (papules/pustules). Penetration into sebaceous follicles is poor, but they produce some improvement after 2–3 months, requiring 4–6 months of treatment for maximal benefit. Treatment should be given for extended periods, since relapse is common if it is stopped. Among the more useful antibacterial agents are tetracyclines, for example oxytetracycline and doxycycline. Alternatives include ciprofloxacin and trimethoprim (Ch. 51). Widespread resistance to erythromycin makes it a less suitable choice.

The anti-androgen cyproterone acetate (Ch. 46) is useful in women with moderate or severe acne and is usually given in combination with ethinylestradiol as a combined oral hormonal contraceptive (Ch. 45). The combination reduces sebum flow by 40%. Alternatively, oestrogen can be given with a non-androgenic progestogen such as norgestimate or desogestrel. Improvement can take 2–4 months.

The anti-androgen cyproterone acetate (Ch. 46) is useful in women with moderate or severe acne and is usually given in combination with ethinylestradiol as a combined oral hormonal contraceptive (Ch. 45). The combination reduces sebum flow by 40%. Alternatively, oestrogen can be given with a non-androgenic progestogen such as norgestimate or desogestrel. Improvement can take 2–4 months.

Isotretinoin is used orally in severe acne and gives an almost 100% probability of complete remission. High doses can produce prolonged remission. Unwanted effects include dry lips, nose and eyes, increased plasma triglycerides and, less commonly, myalgia. Teratogenesis is a major problem and, although the half-life of the metabolites is less than 2 days, conception should be avoided during treatment and for 1 month after stopping treatment.

Isotretinoin is used orally in severe acne and gives an almost 100% probability of complete remission. High doses can produce prolonged remission. Unwanted effects include dry lips, nose and eyes, increased plasma triglycerides and, less commonly, myalgia. Teratogenesis is a major problem and, although the half-life of the metabolites is less than 2 days, conception should be avoided during treatment and for 1 month after stopping treatment.

Choice of treatment for acne

Initially, management of non-inflammatory comedones is by topical treatment such as azelaic acid or retinoids. For early inflammatory lesions a topical antibacterial or benzoyl peroxide can be considered, alone or in combination. More severe inflammatory acne usually requires topical or systemic antibacterials with topical retinoid. Systemic treatment with isotretinoin is used for severe unresponsive acne. Oestrogen and anti-androgen therapy are alternatives for women, and combined oral hormonal contraceptives can be of benefit. Overall, the most common reason for treatment failure is probably non-adherence to the recommended regimen.

True/false questions

1. Atopic dermatitis is the most common form of dermatitis.

2. Oral corticosteroids are the mainstay of treatment of atopic dermatitis.

3. Oral antihistamines reduce itching in atopic dermatitis.

4. Th2-lymphocytes are the dominant immune cells in psoriasis.

5. Immunosuppressant drugs are contraindicated in severe psoriasis.

6. Retinoids reduce cell growth and differentiation.

7. Severe inflammatory acne should be treated with topical or systemic antibacterials.

8. Antibacterial drug resistance in Propionibacterium acnes is rare.

One-best-answer (OBA) question

Choose the accurate statement below about psoriasis and its treatment.

A Psoriasis may be improved by atenolol.

B Psoriasis may be exacerbated by exposure to sunshine.

C Methotrexate has few unwanted effects in the treatment of psoriasis.

D Calcipotriol is a vitamin D analogue applied topically for psoriasis.

E Ustekinumab is a monoclonal antibody against tumour necrosis factor α (TNFα).

Case-based questions

A 7-year-old girl with a history of atopic asthma developed a red, scaly and dry rash in her knee and elbow flexures and on her arms and cheeks. The rash was extremely itchy and she was scratching the affected areas, causing excoriation and weeping. Her mother had had atopic dermatitis when she was young.

1. True. Atopic dermatitis is an inflammatory condition with a familial tendency.

2. False. Corticosteroids are used topically in atopic dermatitis for up to 4 weeks.

3. True. A sedative antihistamine (e.g. promethazine) may be of value, although direct effects on itching are limited.

4. False. Psoriasis is thought to be driven mainly by Th1-lymphocytes, with production of tumour necrosis factor α (TNFα), interleukin (IL)-12 and IL-23.

5. False. The immunosuppressants ciclosporin or methotrexate can be used in severe psoriasis resistant to other drugs.

6. True. Oral retinoids such as vitamin A and its derivatives reduce cell growth and can be used in psoriasis, but may be teratogenic. Oral and topical retinoids are also useful in acne.

7. True. A topical retinoid is used together with oral or topical antibacterials; suitable topical antibacterials are erythromycin and clindamycin.

8. False. Resistance of P. acnes to antibacterials is increasing, including cross-resistance to erythromycin and clindamycin; when possible, drugs with an antibacterial action should be used, such as benzoyl peroxide or azelaic acid.

OBA answer

A Incorrect. Beta-adrenoceptor antagonists can exacerbate psoriasis.

B Incorrect. Regular short exposures to sunlight or ultraviolet light benefit psoriasis by increasing production of vitamin D and slowing skin cell proliferation.

C Incorrect. Methotrexate can produce bone marrow depression and hepatoxicity and regular monitoring is required.

D Correct. Calcipotriol is a topical vitamin D analogue with beneficial actions in psoriasis including inhibition of T-cell proliferation and cytokine release.

E Incorrect. Ustekinumab is an inhibitor of IL-12 and IL-23 and is used in drug-resistant psoriasis; modulators of TNFα (e.g. infliximab, etanercept) are also used.

Case-based answers

A Atopic dermatitis is possible because of the appearance of the rash, the child's atopy, and her mother's history of the condition.

B Initial management approaches should include good skin hygiene with regular bathing (but avoiding soaps), and the use of emollients in bath water and applied topically to moisturise the skin. Drug treatments should include short courses of topical hydrocortisone, and a topical antihistamine or oral sedative antihistamine if the itch is severe, although there is no consensus that antihistamines are beneficial. Topical doxepin may also help reduce itch.

C Contributory factors such as allergies to food and other allergens, psychological factors and removal of irritants and allergens should be assessed. Severe acute exacerbations may require rigorous topical measures and antibacterial treatment.

Bieber, T. Atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1483–1494.

Brown, S, Reynolds, NJ. Atopic and non-atopic eczema. BMJ. 2006;332:584–588.

Haider, A, Shaw, JC. Treatment of acne vulgaris. JAMA. 2004;292:726–735.

Menter, A, Griffiths, CEM. Psoriasis 2. Current and future management of psoriasis. Lancet. 2007;370:272–284.

Naldi, L, Rebora, A. Seborrheic dermatitis. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:387–396.

Purdy, S, de Berker, D. Acne. BMJ. 2006;333:949–953.

Reynolds, NJ, Al-Daraji, WI. Calcineurin inhibitors and sirolimus: mechanisms of action and application in dermatology. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2002;27:555–561.

Schön, MP, Boehncke, WH. Psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1899–1912.

Smith, CH, Barker, JNWN. Psoriasis and its management. BMJ. 2006;333:380–384.

Wasserbauer, N, Ballow, M. Atopic dermatitis. Am J Med. 2009;122:121–125.

Weger, W. Current status and new developments in the treatment of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis with biological agents. Br J Pharamcol. 2010;160:810–820.

Williams, HC. Atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:2314–2324.