Chapter 16 Caring for the person with physical needs, sensory impairment and unconsciousness

Introduction

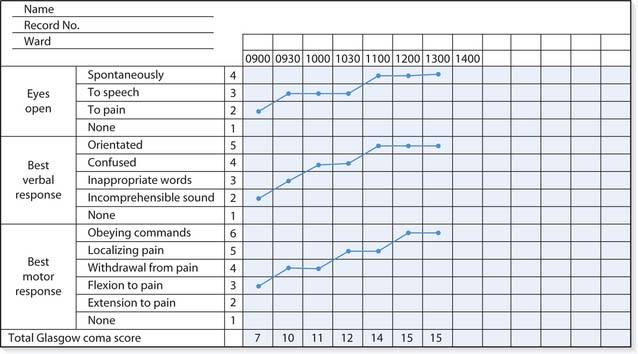

The first section of this chapter explores a range of activities involved in maintaining personal hygiene and appearance, and the factors that may affect them. These activities include many fundamental aspects of care, some of which are highlighted in the Essence of Care (DH 2001), emphasizing that a working knowledge of these aspects of care is an important nursing role and also one in which a nurse can ‘make a difference’. Sometimes the responsible nurse, who remains accountable for the care that clients or patients receive, may delegate these activities to others in the team. In other cases they may form part of a community care package provided to meet social needs or are carried out informally by carers for a relative. Appropriate nursing interventions are discussed to enable holistic assessment and planning when people need help to maintain their personal hygiene and appearance. In each part of this chapter underpinning anatomy and physiology are briefly reviewed to provide the basis for assessing people’s health status and recognizing the presence of abnormalities.

In the middle section, the senses of vision and hearing are reviewed and nursing interventions that will help people with sight and hearing impairment in community and hospital settings are explained.

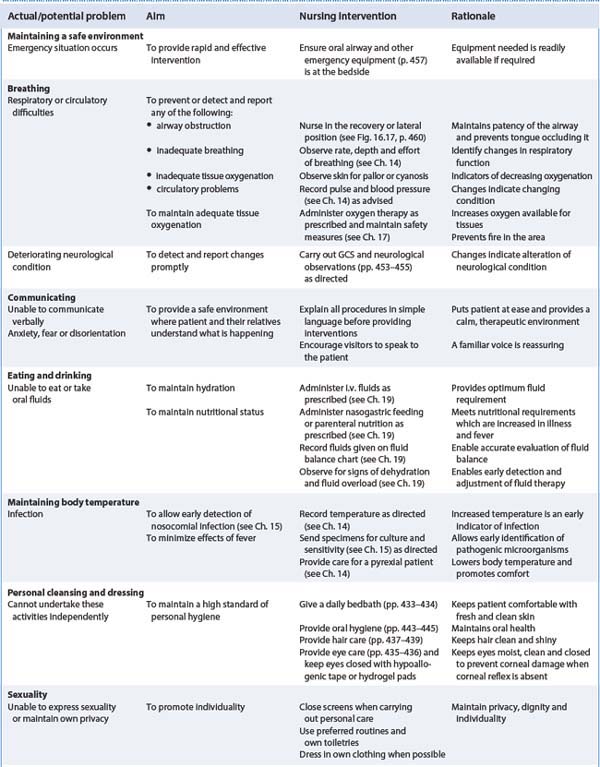

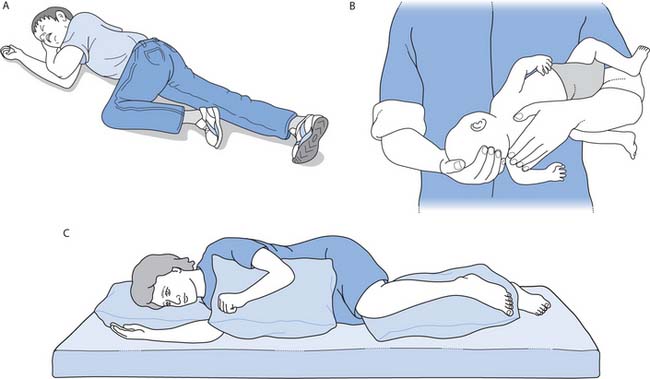

The final section considers unconsciousness and the related first aid interventions. The nursing care required by an unconscious person is then outlined with the following aims:

Personal hygiene and appearance

In this section, factors that affect people’s personal hygiene and appearance are considered and health promotion activities involving nurses are explored. When assistance is needed, nursing interventions are discussed using the evidence base (see Ch. 5), where available. A range of student activities to promote inquiry is included.

For most people, maintaining their appearance and personal hygiene is an important aspect of their daily routines that, once learned, is often taken for granted to a greater or lesser extent. Many different activities are involved, including:

Personal grooming extends to choosing the clothes worn, hair styling and the application of cosmetics and jewellery. The way in which a person chooses to present themselves to others is an integral part of their sexuality.

Children and some adults may need temporary or ongoing assistance with some or all of the activities listed above. Personal hygiene is important for both health and social acceptability and, in most cultures, it is expected that people should be clean and odour free.

Recent attempts to improve fundamental aspects of care in all settings saw the development of best practice statements in the Essence of Care (DH 2001). Those relevant to nursing interventions discussed in this chapter include:

The best practice statements, or benchmarks, come with a resource pack to help nurses and others rate their current practice against them. By identifying and then improving aspects of current practice nurses can work towards meeting these benchmarks. The best practice statements that relate to personal hygiene are shown in Box 16.1.

Box 16.1 Best practice statements: personal hygiene

[From DH (2001)]

Structure and functions of the skin

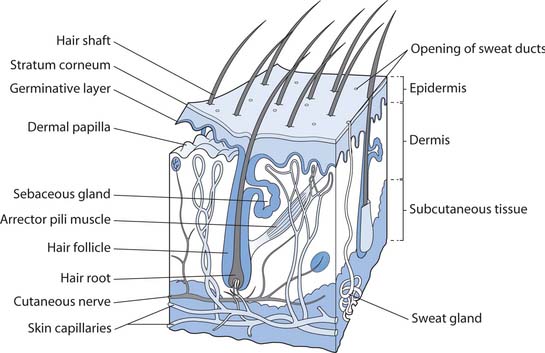

The skin completely covers the body, providing a waterproof barrier between the external environment and underlying internal structures. It is self-renewing and self-repairing and consists of three layers (Fig. 16.1):

Fig. 16.1 The structure of the skin showing its appendages

(reproduced with permission from Waugh & Grant 2006)

Normal skin flora

Following birth the skin surface becomes colonized by commensal bacteria (organisms living in association with another organism, without benefiting it and normally without harming it) and they form the normal skin flora (see Ch. 15). They do not normally cause harm unless they gain entry to a part of the body normally protected by the non-specific defence mechanisms or a person is particularly susceptible to infection, for example when the immune system in compromised following cancer chemotherapy. In hospital, normal flora (commensal bacteria) are replaced by hospital strains that are more likely to be pathogenic (causing illness) and resistant to many antibiotics. This predisposes people to the development of hospital-acquired infection (see Ch. 15).

Appendages of the skin

These include hair and hair follicles, different types of glands and the nails. Hair grows from the bulb at the base of hair follicles (see Fig. 16.1). The arrector pili are small involuntary muscles associated with hair follicles and contraction pulls the hairs erect, causing ‘goose pimples’ on the skin.

Sebaceous glands are present on most parts of the body and become active at puberty. They secrete an oily substance, called sebum, which keeps the hair soft and pliable and the skin supple. It also provides waterproofing and acts as an antibacterial agent, preventing the invasion of microbes.

Sweat glands are also widely distributed throughout the skin and they secrete sweat that consists mainly of water and sodium chloride (salt). Secretion of sweat is increased when either environmental or body temperature is high and by sympathetic nerve stimulation. Excessive sweating leads to dehydration (see Ch. 19). Specialized sweat glands that become active at puberty are found in the axillae and anogenital region. They secrete sweat together with other substances as an odourless milky fluid. When normal flora on the skin act on this, the result is a bad smell, sometimes referred to as ‘body odour’.

Functions of the skin

Intact skin acts as a non-specific defence mechanism by providing a waterproof physical barrier plus chemical (acid mantle) and biological barriers that together protect against microorganisms, chemicals and physical trauma.

Control of body temperature is an important function of the skin, with heat loss determined by the amount of blood circulating through its vast capillary network (see Ch. 14).

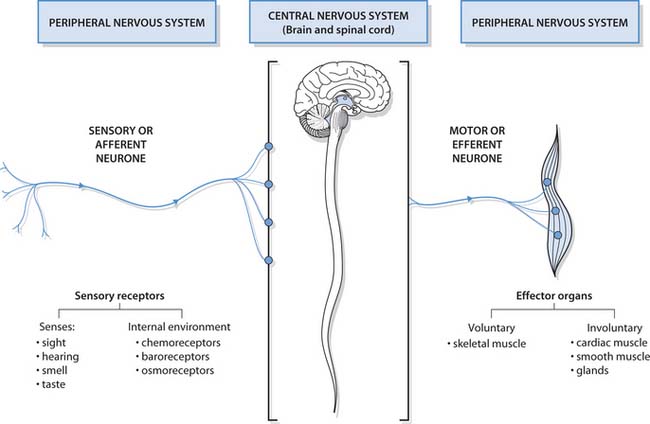

The skin is also a sensory organ with specialized receptors for touch, pain and temperature. Sensation is mediated by the nervous system (Fig. 16.2, Box 16.2, see p. 428) and provides important information about the environment. It protects people from potentially dangerous situations, e.g. burns from very hot objects. The automatic response to touching something very hot is immediate withdrawal from the hot item. Children learn a great deal about keeping safe through cutaneous sensation. When something causes pain, they quickly learn not to repeat the behaviour. Abnormal sensation puts people at risk from environmental hazards, e.g. stepping into a very hot bath causes scalds.

Fig. 16.2 The functional components of the nervous system

(reproduced with permission from Waugh & Grant 2006)

The nervous system consists of two parts:

The nervous system controls and integrates body functions. Put very simply, sensory receptors in the peripheral nervous system respond to stimuli either inside the body or in the external environment. This results in generation of nerve impulses that travel to the central nervous system via sensory nerves. After processing in the central nervous system, responses – again in the form of nerve impulses – are conducted through motor nerves to effector organs in the peripheral nervous system, i.e. muscles and glands. Responses may be either voluntary or involuntary.

For a detailed explanation of the components and functions of the nervous system you should refer to your anatomy and physiology textbook.

Limited absorption and excretion of certain substances takes place through the skin. Many drugs are absorbed through the skin, e.g. those contained in transdermal patches (see Ch. 22).

Assessment of the skin

A person’s skin condition contributes to their body image and the media encourages people to see healthy skin as an attractive attribute. A major threat to healthy skin is from overexposure to the sun either through occupational or leisure activities (Box 16.3, p. 428). People who have skin conditions often consider themselves unattractive to others and suffer from low self-esteem.

Preventing skin cancer

Skin cancer is usually the result of too much exposure to the sun. In the UK, rates are increasing and many people do not take the required precautions.

Risk factors

The SunSmart campaign (Cancer Research UK 2004) advises the following actions to reduce the risks:

Stay in the shade between 11.00 and 15.00 hours

Careful observation of the skin can provide clues about body temperature, hydration and general health of an individual. This can be undertaken informally while speaking to a person when the observant nurse will look at exposed body parts, e.g. the face and extremities, or while recording vital signs. More information can be gained when clothes are removed, e.g. when assistance is needed with activities of living. Formal assessment is needed in some situations, for example, to assess the risk of pressure ulcers (see Ch. 25) and when a person’s primary problem is a skin disorder. The characteristics of normal skin are:

Knowing the normal characteristics will alert the nurse to the need to report any abnormalities, (e.g. redness, clammy skin, rashes, signs of scratching) that may be present. Signs of scratching may indicate a parasitic infestation.

Infestation

This is invasion by a parasite that lives on a host, e.g. head lice (see pp. 438–439) and scabies (Box 16.4). Other infestations include body lice that are rare in developed countries but are sometimes found in rough sleepers who lack the facilities for personal hygiene and washing clothes, and pubic lice, also known as ‘crabs’, that are spread by close contact such as sexual activity and can be recognized by their two large hind claws.

Scabies is caused by infestation of a small parasitic itch mite (Sarcoptes scabei) and is acquired from another person during close physical contact. The female burrows along the epidermal layer of the skin, laying eggs and leaving faeces behind. Areas where the skin is thin, including the finger webs and ankles, are commonly affected. As adult mites develop, they feed and burrow, eventually through most areas of the skin, and chemicals in their excreta cause intense itching. The burrows can often be seen on the skin.

Factors influencing appearance and personal hygiene

Many factors that affect people’s preferences and routines are considered below. Knowledge of these helps the nurse assess a person’s needs so that holistic interventions can be planned and carried out when independence is not possible.

Physical

Many physical factors influence a person’s independence in these activities, leaving them with limited ability to undertake some aspects of self-care through to complete dependence on others to meet their needs. These include frailty, impaired movement or inability to use a limb, unconsciousness, difficulty balancing for any length of time and sight impairment.

Consideration of general mobility will indicate whether assistance to get to the bathroom or the use of a hoist or other equipment is necessary (see Ch. 18). In a care setting, equipment such as an intravenous (i.v.) infusion will reduce a person’s independence in carrying out activities related to maintaining appearance and personal hygiene.

Breathless and debilitated people may be able to carry out some of the activities required but find trying to complete the whole process themselves exhausting.

If a person is in pain, this will affect both their motivation and ability to undertake or tolerate these interventions. When this is the case, it is important to assess their pain and provide analgesia beforehand.

Psychological factors

Most people feel clean and refreshed after a bath or shower. Someone who is depressed, debilitated or lethargic may not have the interest or energy to engage in maintaining their own appearance and hygiene. This may affect dressing and wearing clean, presentable clothes or extend to complete neglect of personal hygiene. The nurse may need to gently encourage these people to attend to their grooming (Box 16.5). This is also important in people with low self-esteem, low mood or altered body image.

Strategies for encouraging personal hygiene

Social, cultural and religious factors

Cultural and religious norms often influence individual practice. Religious requirements include personal hygiene activities, e.g. Hindus and Muslims require their hygiene needs to be met by nurses of the same sex. In Western cultures communal bathing or showering practices vary although in the UK separate facilities for men and women are usually provided, e.g. swimming pools. In many cultures nudity is considered offensive (Box 16.6). The answers you provided for Box 16.6 may have identified more of these factors.

Environmental factors

In Western countries, living accommodation normally includes an indoor lavatory and a fitted bath or shower. Access to and using the bath, shower and toilet may require the installation of adaptations (see p. 433).

Economic factors

When personal income is low, people may be unable to afford adequate heating for the bathroom or hot water for showering. Similarly, there may be little money to spend on basic hygiene requisites including soap, shampoo, toothbrush and toothpaste.

Lifespan factors

At particular stages of the lifespan there are characteristics affecting both independence in carrying out personal hygiene activities and the actual hygiene activities required.

Infancy

In infancy a parent usually carries out bathing routines and personal hygiene. Infants do not produce sebum (p. 427) and therefore their skin is susceptible to maceration (softening of the skin caused by continual exposure to moisture) and this predisposes to nappy rash (Box 16.7).

Box 16.7  EVIDENCE-BASED PRACTICE

EVIDENCE-BASED PRACTICE

[Adapted from Prodigy (2004b)]

Nappy rash

Nappy rash is inflammation of those parts of the skin normally covered by a nappy and is minimized by keeping the skin clean and dry. Neonates (newborn babies up to 4 weeks old) pass urine around 20 times per day – this reduces to about 7 times daily by 1 year. Nappy rash does not occur in developing countries where nappies are not used.

Predisposing factors

Contact with faeces is the most important skin irritant and worsens when diarrhoea occurs. Other contributing factors may include:

Prevention

Childhood

During childhood, independence in toileting, washing and dressing is usually established using significant others as role models, not only but also due to physiological development and maturation of the body systems. Through socialization, children learn that personal hygiene is undertaken in privacy or only in the presence of close family members. However, not everyone achieves independence in these activities. For example, children with severe physical or learning disabilities may always be dependent, to some extent, on others.

Puberty

Puberty occurs during adolescence and is accompanied by physical and emotional changes that focus attention on personal grooming and hygiene. Increasing under-arm perspiration develops, necessitating the use of a deodorant. Girls start to menstruate and in boys there is growth of facial hair.

McKinlay et al (1996) carried out a study on clients with severe learning disabilities and found that many were unable to manage menstruation independently (Box 16.8). Interestingly, the suggestions provided by the clients’ mothers in the study reflect the information needed by any girl before the onset of menstruation.

Managing menstruation

McKinlay et al (1996) identified difficulties in about 50% of clients with severe learning disabilities that included:

Only 20% of clients’ mothers had received advice on this topic and provided the researchers with information that they would have found useful prior to their own experiences.

At this time there is often experimenting with clothing, hairstyles, cosmetics and jewellery while striving to develop an individual personality and sexual identity. Standards of hygiene may change as development influences the young person’s body image and perceptions of self (see Box 16.5, p. 429).

Older adults

In older adults the physical changes of the normal ageing process influence appearance and personal hygiene routines. Age-related changes affecting the skin may impact on nursing interventions and include:

To a greater or lesser extent, hair turns white as the colour pigment melanin is replaced by air. An older person may find they can no longer reach their toenails and may require help to cut them. Toenails become thicker and often grow abnormally. Gum disease, which frequently originates in childhood, can result in loss of teeth and the need to wear dentures (p. 442). Physical frailty can make getting into a bath both difficult and unsafe. When this is the case, or there is visual impairment or reduced dexterity, home adaptations and/or aids may be required (pp. 433, 440).

Assisting with bathing, washing and showering

Nursing assessment identifies a person’s usual routines and preferences in order to understand their habits (see Ch. 14). This includes the frequency, time of day and what the individual can do independently so that holistic and individualized care can be given as required.

When helping people with bathing and washing, it is important to recognize common nursing practices that may not be conducive to maintaining healthy skin, e.g. use of soap (see p. 432).

Assisting a person with their personal hygiene provides a good opportunity to communicate with them. The nurse can identify not only their preferred hygiene practices but also all other aspects of their general well-being and progress. For a dependent person, activities related to personal hygiene can be used to preserve personal choice and individuality when this is not possible in many other aspects of their lives. When a person refuses to undertake any activity, including those concerned with personal hygiene, their wishes must be respected even if this causes the nurse frustration (NMC 2004).

Maintaining privacy and dignity

It is important to remember the importance of privacy and dignity when considering any aspect of personal hygiene, whether assistance is needed or not. The best practice statements (DH 2001) are shown in Box 16.9. These extend to client preference, and Oxtoby (2003) highlights simple interventions, e.g. ensuring bedside screens are completely closed and gowns meet at the back when mobilizing, that will improve people’s privacy and dignity. When assisting people to carry out activities involved in maintaining personal hygiene they are likely to feel embarrassed and helpless. Clients’ feelings may well be similar to those you recalled while completing Box 16.6 (see p. 429).

Box 16.9 Best practice statements: privacy and dignity

[From DH (2001)]

Washing and drying the skin

The skin is usually cleaned by washing with soap, or soap substitute, then rinsed and gently patted dry, with particular attention to skin folds and crevices, e.g. under the breasts and between the buttocks. If moisture remains in skinfolds, either through sweating or inadequate drying, irritation and breaks in the skin can develop. This is known as intertrigo. Nursing practices need careful thought to ensure they do not worsen dry skin which is a common problem, especially in older people (Box 16.10, p. 432).

Box 16.10  EVIDENCE-BASED PRACTICE

EVIDENCE-BASED PRACTICE

Skin care: emollients

The skin:

Emollients

These oil-based substances are applied to soften dry skin. They act by reducing water loss through the skin surface and include:

Drying the skin

Skin conditions can be painful and people with skin disorders may use prescribed preparations for washing. These people may also feel particularly self-consciousness if they need help with washing becauseskin problems can affect self-esteem and body image (see Chs 8, 11, 12 and 21). Children may experience additional problems with peer acceptance.

Bathing and showering

A shower is more compact than a bath. It requires less water and is therefore more economical and environmentally friendly. Skin debris is rinsed away more easily by showering than bathing and, for this reason, Muslims and Hindus use running water for washing whenever possible.

Sometimes people need the nurse’s guidance about how they can have a bath, e.g. covers are available for plaster casts or a limb can be covered in polythene to keep a wound dry while bathing.

Planning is important when assisting patients to ensure:

Bathing, washing and showering is tailored according to individual needs and preferences. When assistance is needed, timing may require planning to fit in with other scheduled treatment or therapies. Analgesia, if needed, should be given beforehand to minimize discomfort. The person should have their own toiletries and follow their preferred routines where possible (see Box 16.1, p. 426). Before taking someone to the bathroom, the nurse should check it is vacant, clean and warm and provide the opportunity for the person to empty their bowels and bladder. A mechanical hoist or other equipment may be needed to transfer a person to the bathroom or into the bath (see Chs 13, 18). Safety in the bathroom is an important nursing consideration and the measures taken to prevent accidental slips or falls are shown in Box 16.11.

Safety in the bathroom

To prevent scalding:

To prevent slips or falls on wet surfaces (involving the physiotherapist and occupational therapist as required):

A towel is wrapped round the person on leaving the bath or shower to keep them warm and maintain their dignity. Principles of bathing infants and children are outlined in Box 16.12.

Principles of bathing infants and children

After bathing or showering, other aspects of personal care are then carried out, including the use of talc, deodor-ant and moisturizer; oral hygiene; shaving and styling the hair. Many women apply cosmetics to complete their appearance.

After use, the bath or shower is thoroughly cleaned according to local policy and left tidy for the next person.

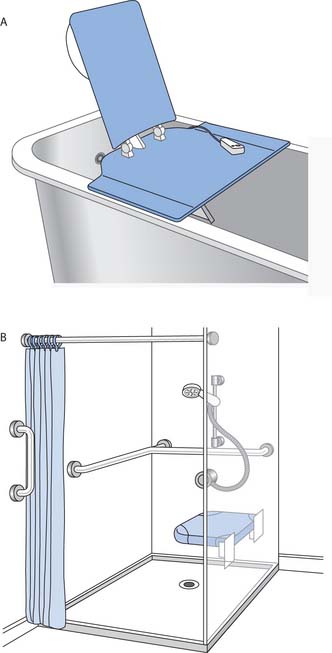

Bathing aids

Bathing aids are often used in care settings and home adaptations can also be provided to enable people to remain independent at home (Fig. 16.4). Home assessment is carried out by an occupational therapist and suitable aids identified. Grab rails can be fitted to the walls to assist people getting into and out of the bath and electric bath lifts lower a person into the bath and raise them up again when required. A hoist can be provided at home although assistance from a carer is needed to use this. A shower with a seat can also be installed for people who find standing difficult.

Menstrual hygiene

Menstruation occurs in women between the menarche (first menstruation) occurring during puberty and the menopause (cessation of menstruation). In most women menstrual periods last around a week and take place about every 28 days. During this time there is vaginal blood loss that can heavy to begin with and then reduces. A supply of sanitary pads or tampons is required to absorb menstrual loss. This may need to be provided in care settings, together with hand washing facilities for dependent people. In Western society managing menstruation is a private, personal activity that is generally a taboo subject.

Bedbathing

A bed bath, or blanket bath, is needed to maintain personal hygiene when a person is unable to use the bath or shower or is confined to bed. These people are usually quite dependent and may also be unconscious or confused.

This affords the opportunity for a period of one-to-one communication. The patient should be encouraged to participate as much as their condition allows. Choice of nightclothes and use of a person’s own toiletries will enable a person confined to bed to have some involvement in their care. The principles of bedbathing are outlined in Box 16.13 (p. 434).

Principles of giving a bedbath

When the bed bath is complete, other aspects of personal care are carried out, including oral hygiene, shaving and hair styling.

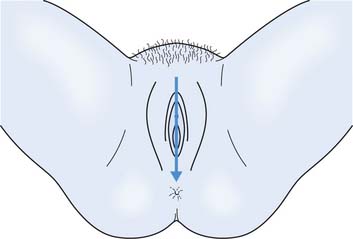

Perineal care

When possible, the patient should be offered the opportunity to carry out personal perineal care themselves (see Box 16.13 and Fig. 16.5). This is often referred to as ‘washing between the legs’ or ‘down there’. Many nurses find carrying out perineal care embarrassing, especially when caring for people of the opposite sex. A dignified and professional attitude will help to put both the nurse and patient at ease.

The nurse must consider cultural needs, e.g. Muslims wash their genitalia in running water after passing urine or faeces. Nurses can provide a jug of water for washing if the person is confined to bed.

Microorganisms normally resident in the bowel are the most common cause infection of the bladder (cystitis). This condition is more common in females whose urethra is shorter and therefore more easily reached by ascending microorganisms (see Ch. 20).

Normally in the male infant the preputial space is incompletely developed, causing the foreskin or prepuce to be adherent to the penis (glans penis). As it is not easily retracted, phimosis (tight foreskin) is normal in early infancy. Through normal development and erections these early adhesions gradually disappear, and the foreskin separates. The foreskin softens and becomes retractable by 2 years of age. Attempts to retract the foreskin for washing etc. before this age must be avoided. However, in uncircumcised men and older male children, the foreskin is carefully retracted and the glans gently washed and dried before the foreskin is repositioned.

Care of the feet, hands and nails

Assessment of the feet is important because problems can often be treated if detected early; without treatment, mobility can become severely restricted. Older people should always be asked if they are able to cut their own toenails as many have difficulty reaching them. The effects of the ageing process on the feet include thickening of the nails and development of calluses and hard skin.

Local policies must always be consulted before trimming nails, because some people are always referred to a podiatrist (a health professional responsible for the management of conditions affecting the feet and/or lower limb) for treatment and cutting of their toenails. ‘At-risk’ people include those with diabetes mellitus (usually known as diabetes) and poor circulation caused by peripheral vascular disease. It is important that people with diabetes are taught how to look after their feet properly to prevent even minor damage that can progress to serious complications (Box 16.14).

Foot care for people with diabetes mellitus

The following care will protect your feet from damage and ensure you identify any problems that occur promptly:

Care of the nails is best carried out after a bath or shower; alternatively, the hands or feet can to be soaked in a bowl of warm water for 15 minutes to allow the nails to soften. A nailbrush can be used to remove obvious matter. The area under the nails is carefully cleaned using an orange-stick or nail file before the hands or feet are dried thoroughly. After drying, the cuticle is gently pushed backwards to prevent it growing over the nails.

Toenails are cut straight across with scissors or clipped using nail clippers. If difficulty is encountered because they are tough, the person should be referred to a podiatrist. Fingernails are usually trimmed using scissors and then filed to the shape of the finger with an emery board. Hand cream and nail varnish is then applied if wished.

Care of the eyes

Anatomy and physiology of the eye is reviewed on pages 445–446 but the importance of the accessory structures of the eye is considered here in order to explain eye care. This may also include care of spectacles, contact lenses or an artificial eye.

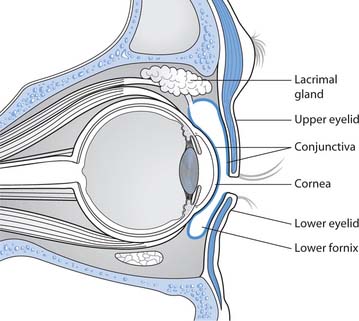

Accessory structures of the eye

These include the eyebrows, eyelids and eyelashes (Fig. 16.6). Together they protect the delicate structures at the front of the eye, especially the cornea, from the entry of sweat, dust and other foreign bodies. For example, when a speck of dust enters the eye, copious amounts of tears are produced and the eye waters profusely in an attempt to wash it away. The conjunctiva is a delicate membrane that protects the cornea and also lines the eyelids.

Tears are continually produced by the lacrimal glands and spread across the cornea during blinking, lubricating it and keeping it moist. They contain an antibacterial enzyme, lysozyme, which protects the eye from infection and drains away through a duct into the nose. The inferior fornix is the site for instilling eye medication (see Ch. 22). The areas where the upper and lower eyelids join are called the:

Eye care

Ensuring the eyes are clean and free from crusting is part of any general hygiene routine and is normally accomplished when washing one’s face. Secretion of tears and blinking keep the eyes clean and moist while awake. Unconscious people are at risk from damage to the cornea because the blink reflex is lost and their eyes are therefore kept closed (see p. 458).

Eye care is required is some situations, e.g. presence of discharge. Sometimes it is an aseptic procedure (see Ch. 15) carried out by trained staff for people who have had surgery or trauma to the eye. In other situations, it is a clean procedure (see Ch. 15) (Box 16.15, p. 436).

Spectacles

Spectacle lenses are made from glass or plastic material and both types should be kept clean using the cloth provided. They can be washed in soapy water and gently dried using a soft cloth to prevent scratching. When not in use, they should be stored in their case (labelled with the person’s name in a care setting) to protect them from scratching and to minimize effects of physical damage.

Glass lenses are relatively heavy and can cause soreness on the bridge and sides of the nose. Lighter lenses made from shatterproof material are also safer, especially when people are in situations where an object may hit their eyes. Irrespective of the type of lenses, spectacles should be checked for comfort and fit. This means checking the sides and bridge of the nose and the back of the ears for signs of soreness. A person may have different pairs of glasses for reading and watching TV, and care should be taken to ensure the correct pair is in use.

Contact lenses

Contact lenses are thin transparent discs inserted onto the cornea to correct refractive errors of the eye. They float on a layer of tears and can be hard, soft or gas permeable. The solutions required for the care of the different types of lenses vary and are used according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Each lens is kept in a separate labelled container as the two lenses may have different prescriptions.

Handwashing before insertion or removal is essential to minimize the risk of infection or introduction of foreign bodies that will cause inflammation of the conjunctiva (conjunctivitis) or corneal ulcers. Contact lenses are normally removed at night and should not be used when a person is receiving ophthalmic (eye) medication. Use of daily disposable contact lenses eliminates the need for cleaning and storage.

Artificial eyes

An artificial eye, or ocular prosthesis, is required after removal of the eyeball. This may be following trauma, severe infection or removal of a tumour. An artificial eye may be a permanent prosthesis. When it requires care, people usually prefer to carry this out themselves. If assistance is needed, advice from the nurse specialist or ophthalmology department should be sought.

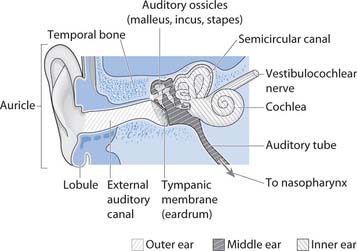

Care of the ears

In order to carry out safe care of the ears it is necessary to be familiar with two important structures: the external auditory canal and the eardrum, or tympanic membrane (see Fig. 16.14, p. 449). Anatomy and physiology of the ear and hearing is outlined on page 449.

It is important to wash the skin covering the external ear as part of bathing or showering. Children often forget to wash behind their ears (Trigg & Mohammed 2006). The ears should be cleaned daily by gentle insertion of the corner of a moist flannel and rotating it into the external auditory canal. Nothing else should ever be inserted into the ear (except a tympanic thermometer or an otoscope). Cotton buds and other objects should not be used to try to remove wax because they can push it further into the external auditory canal and also damage the eardrum (Harkin & Vaz 2003). Hearing impairment may occur when there is build up of wax in the external auditory canal. Excess wax can be removed by irrigation (previously called syringing), a procedure that requires special training. Any discharge from the ear is abnormal and should be reported immediately.

Small children are prone to putting small items into their ears. A foreign body can cause deafness when the external auditory canal is blocked and may also damage the eardrum. Although foreign bodies in the ear are much more common in children they do occur in adults. They also occur in people who unadvisedly use cotton buds or other objects to deal with earwax.

The first aid interventions required should this occur are as follows:

Hearing aids

The Royal National Institute for Deaf and hard of hearing people (RNID) (2004a) estimates that two million people in the UK have hearing aids, but a quarter of these people do not use them regularly. A further three million people have a hearing impairment and would benefit from having a hearing aid.

Adapting to using a hearing aid takes time and initially it is worn for short periods that are gradually increased. Hearing aids are described as analogue or digital, depending on the technology they use. Digital hearing aids process sounds better than analogue hearing aids. The NHS provides, repairs and replaces certain hearing aids free of charge although some people choose to buy their own.

Hearing aids are battery operated and are worn in or around the ear. They amplify sounds but do not restore natural hearing. There are three main designs: body-worn, behind-the-ear and in-the-ear.

Body-worn aids have a small box that can be clipped to clothing. People with severe hearing impairment often use them as they provide the most powerful amplification. They are also widely used by people who also have poor vision and those who find using the controls of behind-the-ear models difficult. In-the-ear aids are not suitable for people with severe hearing loss. The behind-the-ear aid is the most commonly used (Fig. 16.7). They have a small control switch with letters that mean:

The microphone detects sound and must be kept clean and dry. The volume control wheel can be adjusted to suit different environments although this requires reasonable manual dexterity. The battery compartment opens, allowing the small battery to be changed. These should be kept out of children’s reach as they can swallow them or poke them into their ears or nose. The plastic tubing transmits sound to the ear mould that is specially made for the wearer and should fit snugly. The plastic tubing and ear mould are wiped with a tissue after use. They are disconnected from the elbow and washed in soapy water and dried at least weekly. The plastic tubing needs to be replaced every few months.

Care of the nose

The nose does not normally require special care. Gentle blowing into a handkerchief or tissue removes excess secretions and debris. The use and prompt disposal of tissues is encouraged in care settings to reduce the risks of cross-infection. Harsh blowing should be avoided as it can cause damage to the eardrum and nasal mucosa. When there is a tube situated in the nose, for example a nasogastric tube, there may be accumulation of secretions that can be gently removed using moist swabs or cotton buds.

Children are prone to inserting small objects into their noses causing pain, trauma, blockage and, some days later, infection.

Hair care

The appearance of a person’s hair normally contributes to their self-esteem, personal identity and sexuality. It also provides an indicator of their well-being and is usually clean and shiny. When tangled, dull or unkempt this suggests low self-esteem, low mood or that the person is physically unable to carry out hair care independently.

Most people style their hair using a brush or comb, at least daily. Fine-toothed combs are suitable for short hair; broader toothed ones are better for people with long or curly hair. People with impaired movement of the shoulders or poor handgrip find hairbrushes or combs with large handles easier to use. Brushing keeps the hair clean by removing dead epithelial cells and dust from the scalp and hair.

Haircutting is usually carried out at regular intervals and its style contributes to a person’s individual and cultural identity. This aspect of personal hygiene is one of the least private and is normally carried out communally at a hairdressing salon. For people unable to get out and about, arranging for a hairdresser to visit them at home or in a care setting often provides a psychological boost. Hair cutting must never be undertaken without consent of the person involved because some people do not cut their hair for religious or cultural reasons, e.g. Sikhs and Rastafarians. Nurses should be aware of the religious and cultural hair care needs of people in their care. Examples of these are outlined in Box 16.16 (p. 438).

Box 16.16 Hair care – cultural and religious needs

People of certain faiths keep their hair covered, including:

Moreover, in Sikhism, two of the Symbols of faith (the ‘5 Ks’) are to do with the hair:

(Note: the other Symbols of faith for Sikhs are the kara (steel bangle), the kirpan (symbolic dagger) and the kaccha (shorts/underpants).

African-Caribbean people tend to have brittle, crinkly hair and use wide-toothed combs to reduce discomfort and breaking. Pomade is an oil-based product used to enhance shine and smoothness of this type of hair. It is rubbed into the hands and then applied to the hair and scalp. Damp hair may be braided or pleated, but loosely because it tightens as it dries.

Hairwashing

Hairwashing frequency varies considerably between individuals; younger people commonly wash their hair daily although many other people wash their hair less often. Without washing, the hair becomes greasy as dried sweat and sebum accumulate.

Hairwashing can be carried out as a separate activity or during showering or bathing. Debilitated people often appreciate help with this at a sink in the bathroom. Helping someone style their hair provides a good opportunity for one-to-one communication and improves their self-esteem. It is important to include the person in decisions about styling when possible to avoid unwanted or inappropriate looks and effects. Chemotherapy and radiotherapy treatment often cause alopecia (hair loss) and people receiving these treatments are given individual advice about hair care. When hairwashing with shampoo and water is not possible or practical, dry shampoo can be used instead. Hairwashing can also be carried out in people confined to bed (Fig. 16.8); the principles for this are shown in Box 16.17.

Principles of hairwashing in bed

Head lice

The presence of head lice (Pediculus capitis) is also known as pediculosis but, importantly, the presence of nits (the empty cases that remain stuck to the hair after the eggs have hatched) does not indicate current infestation.

Eggs, commonly known as nits, are laid by adult females and firmly cemented to hair shafts near the scalp. The eggs hatch after 7–10 days and adults live for about 1 month. Adult head lice are tiny insects found in the hair with peak prevalence in children between the ages of 4 and 11 years. They are usually found behind the ears and round the hairline. Infestation is often accompanied by intense itching of the scalp and scratching can cause secondary infection.

Fortunately, head lice do not transmit disease to people but there is considerable stigma and social distress associated with their presence. This is compounded by widespread myths and misconceptions about the means of spread and treatment of head lice. They affect people from all socioeconomic groups and show no preference between clean or dirty hair. Head lice can neither jump nor fly. People who have been in close contact with an infested person should be identified and treated if lice are found. They are spread by direct contact with an infested person and cannot survive for long away from the host. There is a lack of evidence to support the commonly held belief that spread occurs through sharing of hair brushes, combs, hair ornaments, hats and scarves (Koch et al 2001, Prodigy 2004c). Treatments are summarized in Box 16.18.

Box 16.18  EVIDENCE-BASED PRACTICE

EVIDENCE-BASED PRACTICE

[Adapted from Prodigy (2004c)]

Treatment of headlice

Treatment can be chemical or mechanical.

Increasing concern about the effects of pesticides, especially on children, is encouraging research into the effectiveness of different treatments. However, there continues to be a lack of consensus about which is best (Prodigy 2004c). A recent study by Burgess et al (2005) suggests that a new chemical may be less irritant to the scalp and less sensitive to resistance than others currently used.

Patient information leaflets are available from Prodigy (2004a)

Continued presence of head lice after any treatment may be the result of:

Care of facial hair

A moustache and beard need daily grooming. Electric trimmers can be used when requested but trimming or removal should never be undertaken without the person’s permission as any facial hair may have personal, cultural or religious significance. In frail or debilitated people gentle wiping or washing after meals easily removes any food debris.

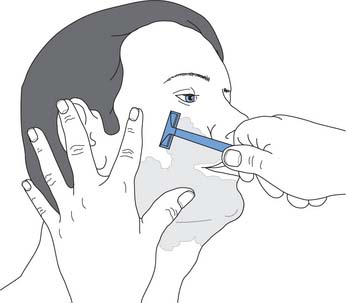

Shaving is best carried out after bathing when the skin is softer. It forms part of many men’s daily hygiene routines and being unshaven makes many feel unclean. An unkempt appearance can quickly develop, especially in the eyes of their relatives.

Many men use an electric shaver, which is a safe, convenient method that is encouraged in those people who are prone to bleeding because they are taking anticoagulant medication or have a clotting disorder. Electric shavers should never be shared because of the risk of cross-infection.

Wet shaving is other men’s personal preference. When assistance is required, the person’s usual routine should be followed. The face is washed and shaving cream applied and worked gently into the skin until lather is formed. Shaving is carried out using small, firm strokes of the razor in the direction of hair growth over taut skin. The razor is rinsed frequently. People often make facial movements that tighten their skin during shaving to provide a closer shave. The face is usually shaved before the neck. Assistance if needed can be provided by the nurse (Fig. 16.9). Any moles or other lesions should be avoided. When shaving is complete, the face is washed thoroughly. Shaving and the use of aftershave contribute to men’s personal identity and sexuality.

Some women normally have more facial hair than others. Excessive facial hair can result from drugs, some endocrine conditions or reduced oestrogen secretion after the menopause. Facial hair in women can be removed either with appropriate depilatory creams or waxing, or disguised using bleaching agents. On no account should it be plucked or shaved unless this is what the woman usually does. Permanent removal, using electrolysis, can be undertaken in certain situations.

Dressing

The clothes people wear normally reflect their traditions and culture. Cultural differences in acceptable modesty exist, especially regarding women who may be expected to wear skirts, cover their legs or cover their faces. Some Muslim women are traditionally clothed from head to foot. Clothes also reflect one’s mood and communicate feelings and individuality.

Contemporary clothing is normally made from material that can be easily washed and needs minimal ironing. The type of clothes worn also depends on the context – working clothes often differ from those worn on informal social occasions. Formal social occasions, such as weddings and funerals, often have specific dress codes.

The type and amount of clothes in a person’s wardrobe is largely determined by their personal income but also by their hobbies and interest in appearance.

When deciding what to wear, the type of activities that will be undertaken and ambient temperature need to be taken into account. In a cold environment, several thin layers provide more insulation and therefore warmth than one thick layer. This has the additional advantage of allowing the wearer to take off a layer at a time as the temperature increases. In hot environments, thin, pale-coloured clothes made from natural fibres are often preferred because they reflect light and absorb more sweat than synthetic materials. In some situations special clothing is required to maintain health and safety, e.g. UK law requires that a crash helmet be worn when riding a motorcycle.

Everyone should have their own clothes wherever they live. People should be offered choice when selecting clothes to wear although sometimes assistance is needed in making appropriate choices.

Help is sometimes needed with dressing, e.g. if there is a weak limb or side, the affected limb is put into blouses, shirts or trousers first. The same strategy is used when equipment such as i.v. infusion is in use.

Dressing aids

Adaptive devices or aids are available to make dressing easier, especially for people who have difficulty bending or have poor manual dexterity. They can be used to assist with many different items of clothing including socks, stockings, tights and jackets. Fastening clothes can be made easier by using:

The Disabled Living Foundation (2004) demonstrates many of these items. People with visual impairment sometimes use a tactile code such as sewing differently shaped buttons on the inside of garments or sewing tags in different places to tell what colour their clothes are. Those people who have red–green colour blindness may also have a system to distinguish colour, especially of their socks.

Prostheses

Dentures are discussed later in this chapter (p. 442).

People may use a prosthesis or accessories for cosmetic or clinical reasons. For example, a wig can be used as an accessory for a change of appearance but in other situations it is worn to hide alopecia, or hair loss, which may occur naturally or following cancer treatment. People who wear wigs for the latter reasons can be self-conscious, both when wearing them and also if they need to removed for any reason.

An artificial limb will often affect a person’s ability to carry out bathing and showering independently. External breast prostheses are sometimes used following surgical removal of a breast. Many women find them difficult to adapt to because they feel mutilated and unattractive after surgery (see Chs 12, 24).

When it has been established that a person uses a prosthesis the nurse should adopt a tactful approach to identify how and when it is used and any impact it may have on their ability to carry out personal hygiene activities. It is important to consider the person’s dignity and ask them prior to removing it for any reason.

Summary – personal hygiene

In summary, assisting someone with personal hygiene and dressing can initially appear simple but tailoring help to meet individual requirements can prove more complex. Box 16.19 provides an opportunity to consider aspects of personal care and the factors that can influence it.

Factors that influence personal hygiene and appearance

Manjit Singh Dhillon is a Sikh client you meet during a home visit with the district nurse. He is 85 years old and recently widowed. He is frail and appears rather unkempt. His clothes are also in need of laundering. During your visit Mr Dhillon tells you about the importance of the symbols of Sikhism (the 5 Ks).

Dental health and oral hygiene

This section reviews anatomy and physiology relevant to the maintenance of oral functioning and health. Effective care required to maintain oral health is considered and the nurse’s role in maintaining dental health and oral hygiene discussed.

Oral care is a basic hygiene need in both healthy and sick people. The teeth are essential for biting and chewing a normal healthy diet. For many people, having attractive teeth is an important aspect of their personal appearance and self-esteem.

Anatomy and physiology: the mouth

The mouth, or oral cavity, is the first part of the digestive tract (see Chs 19, 21). The tongue consists of voluntary muscles that enable speech, chewing and swallowing and it is covered with mucous membrane. Taste buds are present in the tongue and the sense of taste relies on the presence of saliva for dissolving chemicals in food to activate the taste receptors. The cheeks and gums are also lined with mucous membrane. The lips are involved in speech and non-verbal communication.

Salivary glands

The three pairs of salivary glands secrete between 1000 and 1500 mL of saliva into the mouth daily. Saliva is essential for a healthy, comfortable mouth and is composed mostly of water. Its effects include:

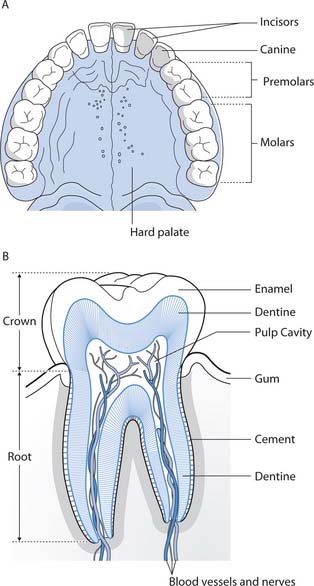

Teeth

Teeth enable people to eat solid food. At birth there are 20 temporary or deciduous teeth, 10 within each jaw. They erupt between the ages of 6 months and 2½ years (Table 16.1). These are known as the temporary teeth or primary dentition. From around 6 years they are shed and, in time, are replaced by 32 permanent teeth, known as the secondary dentition. There are four different types of teeth (Fig. 16.10A), their shapes being suited to their functions. The incisors and canine teeth are used to bite and tear food; the posterior premolars and molars, with their broader, flat surfaces, are used for chewing and grinding food. The four posterior molars are commonly known as the ‘wisdom teeth’.

Table 16.1 Eruption of the primary dentition (after McDonald & Avery 1994)

| Average age of eruption (months) Upper teeth | Teeth | Average age of eruption (months) Lower teeth |

|---|---|---|

| 10 months | Central incisor | 8 months |

| 11 months | Lateral incisor | 13 months |

| 19 months | Canine | 20 months |

| 16 months | First molar | 16 months |

| 29 months | Second molar | 27 months |

Fig. 16.10 A. Types of teeth (second dentition). B. Structure of a tooth

(reproduced with permission from Waugh & Grant 2006)

All types of teeth have the same basic structure (Fig. 16.10B). The crown protrudes through the gum, or gingiva, and the root lies embedded in the jawbone. A hard layer of dentine surrounds the central pulp cavity that contains blood vessels and nerves. The crown has an outer coating of enamel while the root has a layer of cement that holds the tooth firmly in its socket.

Maintaining oral health

Dental health promotion aims to reduce tooth and gum disorders and preserve people’s natural teeth. Establishing good oral care and dietary habits therefore begins in childhood (Box 16.20).

[From British Dental Health Foundation (2004a)]

Maintaining healthy teeth

Teething can be a troublesome time for both infants and their parents. It only occurs during eruption of the primary dentition that begins from around 6 months. Some infants experience drooling and may bite on hard objects while teething, although others can be very irritable.

Regular visits to the dentist from an early age enable discovery of the characteristic smells and sounds of the dental surgery through non-threatening situations. Tooth brushing by parents should begin when the teeth erupt and continuing assistance is needed until manual dexterity is sufficiently developed at around 7 years.

Eating habits should include sugary foods only at mealtimes and non-sugary foods such as cheese or fresh vegetables for snacks between meals. Sugary drinks should never be put in babies’ feeding bottles to avoid the risk of dental caries (decay), especially at night. Sugar-free medicines are widely available and encouraged for the same reasons.

During childhood and adolescence falls and trauma can damage the teeth and mouth. Measures to minimize potential hazards and resultant injuries should be considered, including:

The mouth has an extensive blood supply and trauma that causes damage to teeth is likely to be accompanied by profuse bleeding from damaged oral tissues.

Oral care

Effective oral care moistens and cleans the mouth, removes unpleasant tastes and freshens the breath.

Toothbrushing and flossing

Dental health and oral hygiene are maintained by brushing the teeth with toothpaste at least twice daily and ideally also after meals and sugary snacks. This is the most effective way of removing plaque (a sticky film of bacteria that forms on the teeth) and food debris from the teeth and maintaining healthy gums. A small or medium size brush with soft or medium bristles will make it easier to clean the back teeth that can be hard to reach. The toothbrush is held at 45° to brush each surface of each individual tooth. Tooth brushing should take 2 minutes. The amount of toothpaste needed is the size of a pea.

Toothbrushing is followed by daily interdental cleaning with special brushes or by flossing from around 8 years of age. To do this, dental floss is inserted between each tooth in turn and a seesaw action used to pull the floss backwards and forwards between the surfaces. This removes food debris and plaque from the gums and spaces between the teeth that a toothbrush cannot reach. Flossing reduces gingivitis (inflammation of the gums) but should be undertaken with care by people receiving radiotherapy or chemotherapy because their gums are prone to inflammation, bleeding and infection.

People with poor manual dexterity can hold toothbrushes with large handles more easily. Electric toothbrushes tend to have larger handles and also reduce the manual effort needed to brush the teeth.

Care of dentures

Dentures should fit well and provide a good cosmetic appearance. Ill-fitting dentures cause discomfort, difficulty with eating and inflammation, candidiasis (thrush) or ulceration of the gums and oral mucosa.

They can be cleaned using a toothbrush and non-abrasive denture toothpaste although the British Dental Health Foundation (2004b) suggest that a soft nailbrush and ordinary soap are also suitable. Brushing should be carried out over a sink containing water or a soft towel to prevent damage if they are dropped. All surfaces should be carefully cleaned. The person’s gums and palate are also brushed and the mouth well rinsed. After brushing, the dentures may be soaked in an effervescent denture cleaner to remove staining and bacteria. Dentures should not be soaked in these solutions overnight (British Dental Health Foundation 2004b). They are more easily inserted when they are wet and therefore do not need to be dried.

Removal of dentures can be embarrassing as people are likely to feel self-conscious without them and may also have difficulty in speaking clearly. Some people sleep with their dentures in situ while others prefer to keep them in a denture pot at the bedside. They should be soaked in water to prevent warping or cracking. Denture pots should be labelled in care settings to avoid mix-ups.

People who wear dentures should still visit the dentist for preventative examinations to ensure they continue to fit well and to detect any oral problems, e.g. oral cancer, at an early stage.

Tooth and gum disorders

Disorders include dental caries, periodontal disease and malocclusion.

Dental caries

Discoloration and then cavities, or caries, develop in the teeth when bacteria present in plaque react with carbohydrates, converting sugars into acids that slowly dissolve tooth enamel. The most susceptible periods are between 4 and 8 years (primary dentition) and between 12 and 18 years (secondary dentition).

If plaque is not removed by brushing the teeth, it hardens forming tartar. Tartar cannot be removed by toothbrushing and accumulation results in gingivitis. The gums are reddened, ulcerated and prone to bleeding when the teeth are brushed. Tartar can only be removed by a dentist or dental hygienist.

Periodontal disease

This results from long-standing gingivitis and becomes increasingly common from the third decade although it often originates in childhood. There is destruction of the gum structures that support the teeth and this accounts for considerable tooth loss in later life. Prevention is by encouraging good dental health from childhood (see Box 16.20, p. 441).

Malocclusion

Malocclusion occurs when the upper and lower teeth do not meet normally because they are uneven, overcrowded or overlapping or when the jaw does not develop normally. Biting and chewing are difficult, there is abnormal wear on the teeth, trauma to oral mucosa and the teeth may also have a poor cosmetic appearance. Orthodontic treatment involving the use of dental ‘braces’ is usually required in the teenage years to correct this.

Oral assessment and oral hygiene

The mouth has a role in eating and drinking, taste and breathing, and verbal and non-verbal communication, including intimate self-expression (see Ch. 9). If the mouth is causing discomfort this can have a detrimental psychosocial impact in addition to more physical effects including loss of taste, loss of appetite and resultant constipation. Dehydration causes oral dryness and discomfort (see Ch. 19). A dry mouth can also create difficulty with speaking and is exacerbated by mouth breathing and oxygen therapy (see Ch. 17).

Assessment provides a baseline that enables planning and implementation of individualized care and from which oral status can subsequently be evaluated. Best practice statements from the Essence of Care (DH 2001) show benchmarks for good oral hygiene practice (Box 16.21).

Box 16.21 Best practice statements: oral hygiene

[From DH (2001)]

The oral cavity is carefully inspected using a pen torch and spatula. Signs of a healthy mouth include:

Any abnormalities such as redness, dryness, ulceration and a dirty or coated tongue are recorded together with the presence of capped or crowned teeth, fixed braces or dentures. A wide range of factors may cause oral problems (Box 16.22) and if a person in your care has one or more of these, oral assessment requires careful consideration.

Box 16.22 Factors predisposing to oral problems

Oral assessment tools

Several of these tools have been developed, taking the condition of the oral cavity and a variety of risk factors (see above) into account; however, they have not been sufficiently tested for validity and reliability to recommend them for general use. Roberts (2000a) reviewed some of these tools and then compiled an assessment and intervention tool for older people (Roberts 2001). This is based on a questionnaire and also suggests appropriate nursing interventions. Freer (2000) developed an assessment tool with a scoring scale for use in a neurosciences unit.

Oral hygiene: nursing interventions

When assistance is required with oral hygiene, thoughtful nursing intervention can make a difference; however, Adams (1996) suggests that patient preference is not always taken into account. The aims of nursing interventions are to:

When possible, people should be encouraged to carry out their own oral hygiene. For many people, only assistance to get to a sink, where they can stand or sit and brush their own teeth, may be required. A person in bed or sitting in a chair can often also brush their own teeth when provided with a glass of water and a receiver for collecting wastewater.

When nursing intervention is required an evidence-based approach should be used to select an appropriate technique and solution (Table 16.2). Medication can be prescribed for oral hygiene, e.g. in people undergoing treatment for cancer who have specialized needs (Mallett & Dougherty 2000).

Table 16.2 Techniques and solutions used for oral hygiene

| Technique or solution | Advantages and disadvantages |

|---|---|

| Technique | |

| Toothbrush | Gentle use of a soft, small toothbrush followed by rinsing the mouth can be used when there is no inflammation of the oral cavity. This removes plaque and debris from the teeth and gums, and reduces coating of the tongue (Mallett & Dougherty 2000) |

| This technique requires the person to be able to swallow, rinse their mouth and void wastewater safely | |

| Mouthwash | Providing a mouthwash will refresh the mouth when dehydration or nausea is present and after vomiting |

| The effect is short lasting and mouthwash therefore needs to be offered frequently | |

| A mouthwash requires the person to be able to swallow, rinse their mouth and void wastewater safely (see Solutions, below) | |

| Moistened foamsticks | These are widely used in oral hygiene to clean and moisten the oral mucosa but they are not effective in removing plaque from the teeth (see Solutions, below) |

| Although there is awareness within the profession that patients may be at risk from biting off and swallowing or inhaling the foam, Roberts (2000b) could not find evidence in support of this concern despite an extensive literature review | |

| Foamsticks are suitable for use in people who cannot swallow or rinse their mouths out safely | |

| A swabbed finger | A moist swab round a gloved finger is also effective for cleaning and moistening the oral mucosa; however, it may cause compression of food debris and plaque into the interdental spaces. Plaque is not removed |

| This can be used when a patient is unable to use a mouthwash or swallow safely | |

| This technique is not recommended for children or others who may bite the swabbed finger! | |

| Solutions | |

| Water and normal saline | Both are readily available, convenient and economical solutions to use |

| There is insufficient evidence to recommend saline mouthwashes (Bowsher et al 1999) | |

| Thymol tablets | These are widely used and prepared according to the manufacturer’s instructions – normally, one tablet to one glass of water |

| There is no evidence supporting the benefits of their use and some people find the taste unpleasant | |

| Chlorhexidine gluconate | Used as a mouthwash, this solution reduces bacteria and is effective against plaque |

| Long-term use can cause reversible staining of the teeth and tongue | |

| Sodium bicarbonate | Careful dilution (1 level teaspoon in 500 mL; Nicol et al 2004) is required when using sodium bicarbonate because it is strongly alkaline and can damage the oral mucosa. It also has an unpleasant taste |

| There is a paucity of evidence to support its use although it removes mucus and other debris present in the oral cavity | |

| It should only be used with care and when other solutions have proved ineffective | |

| Saliva substitutes | For a persistent dry mouth, these sprays are effective for 1–2 hours |

Pieces of fresh pineapple or tinned pineapple chunks contain a protein-digesting enzyme that cleans the tongue (Rattenbury et al 1999). Chewing or sucking them is also refreshing and stimulates salivation.

A technique no longer recommended is the use of a swab wrapped round a pair of forceps because this can damage the oral mucosa (Bowsher et al 1999, Roberts 2000b). Some solutions are also no longer recommended: lemon and glycerine should not be used because the osmotic action of glycerine dehydrates the oral mucosa and the acidity of lemon juice may damage tooth enamel (Bowsher et al 1999); hydrogen peroxide damages granulating tissue and should also be avoided (Roberts 2000b).

There is little evidence to support an optimal frequency for oral hygiene although this is suggested to be between 2 and 6 hourly in ill people. It is often appropriate to moisten the mouth with water, a mouthwash or ice chips more frequently. Chewing gum stimulates salivation and, when sugar-free, does not harm the teeth. A person’s fluid status (see Ch. 19) should be reviewed when a dry mouth persists as dehydration is not reversed by providing oral hygiene.

Lip salve or soft paraffin may be used to moisturize and prevent cracked lips. It forms an oily film that reduces water loss by evaporation.

Sensory considerations

When planning care, nurses need to consider the effects of sensory impairments on a person’s ability to self-care and the implications for effective communication. This section of the chapter introduces some issues related to poor vision and hearing and appropriate nursing interventions.

The eye and vision

The eye is the organ for sight and vision and provides people with important information about their environment and those things in it. It is estimated that around 80% of the sensory information perceived is visual.

Anatomy and physiology of the eye (see p. 435 for accessory structures)

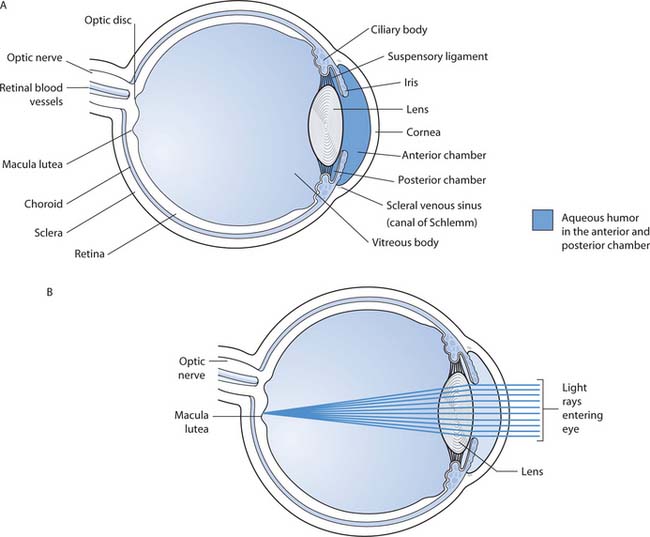

The eyeball consists of three layers (Fig. 16.11A):

Fig. 16.11 A. Structure of the eye. B. Focusing of light rays on the retina

(reproduced with permission from Waugh & Grant 2006)

The anterior segment of the eye contains aqueous fluid. It is secreted by the ciliary glands and drained away through the scleral venous sinus (see Fig. 16.11A). As production and drainage of aqueous fluid is fairly constant the intraocular pressure in the anterior segment also remains relatively constant.

Light rays entering the eyeball are refracted, or bent, as they pass through the transparent structures at the front of the eye. The lens focuses the light rays towards the retina where a visual image is formed (Fig. 16.11B, p. 445). This stimulates the light-sensitive receptors of the retina, generating nerve impulses that are conducted to the cerebral cortex. Each eye forms an image and both generate impulses that are transmitted to the brain for processing. Binocular vision provides accurate information about the environment, including the speed and distance of objects. If there is only one eye with vision, less detailed information is perceived. This means that even simple visual judgements, such as putting a cup down safely, are more difficult. Visual perception is a complex process and interpretation of visual stimuli seldom occurs alone but takes place alongside that of others, e.g. hearing, taste and smell.

Accommodation of the eye describes the changes that take place to allow focusing on near objects, i.e. those closer than 6 m:

Visual acuity

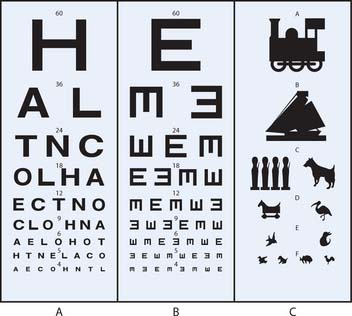

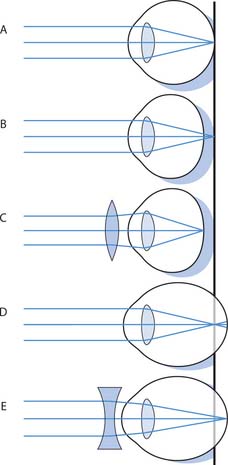

Eye testing measures visual acuity (VA) to measure visual clarity. The most common method is the ‘Snellen type test chart’. The test chart (Fig. 16.12A) is situated in a well-lit area and measurement is carried out 6 m from the chart. This represents ‘distant vision’ where no accommodation is required. Normal vision is 6/6, meaning that the person can read line 6 at 6 m from the chart. When only the top line can be read, the VA is 6/60. If the top line on the chart cannot be read at this distance, the individual is moved nearer to the chart; if the top line of the chart can be read at 3 m, this is recorded as 3/60. The eyes are tested separately with and without spectacles, if appropriate. For people who cannot speak or read English or those with learning disabilities, alternative charts can be used such as the Snellen ‘E’ chart (Fig. 16.12B). A chart depicting objects of decreasing size (Fig. 16.12C) can be used in prelingual children.

Fig. 16.12 Snellen test type charts: A. Snellen letter. B. Snellen ‘E’. C. Recognition of objects

(reproduced with permission from Peattie & Walker 1995)

Fig. 16.13 Refractive errors of the eye and corrective lenses. A. Normal eye. B. Hypermetropia (longsightedness). C. Hyper-metropia corrected. D. Myopia (shortsightedness). E. Myopia corrected

(reproduced with permission from Waugh & Grant 2006)

Sight impairment

Box 16.23 outlines some common types of sight impairment and there are many causes. Diabetes mellitus is a common cause of blindness when the effects of poor blood glucose control damage the retina.

Box 16.23 Types of sight impairment

The Royal National Institute of the Blind (RNIB) (2004a) estimated more than 75% of people over the age of 75 have impaired vision, meaning that most older people have some degree of sight impairment. Less than 10% of people with severe or moderate sight impairment are born with impaired vision.

The presence of severe sight impairment does not mean that a person is completely without sight. For the purposes of registration in the UK sight impairment is described as severe when a person can only read the top line of the test chart at 3 m (VA 5 3/60). Moderate sight impairment can be registered when VA 5 6/60. People who can see further than this in either situation above may also be eligible for registration when their visual field is very limited.

Describing sight impairment

The term ‘severely sight impaired’ describes those people previously referred to as ‘blind’; ‘moderately sight impaired’ describes those previously known as ‘partially sighted’. Some people do not like any of these terms because they feel they are negative and misleading. They may prefer to be described as ‘visually impaired’ or as having ‘impaired vision’ or ‘visual disability’ if they cannot see or are unable to see clearly.

Helping people with sight impairment

Nurses should be aware of the common incidence of visual problems, especially in older people who may not have recognized this themselves. They may observe behaviours that suggest sight impairment that warrant further investigation. These include:

It is recommended that people over 60 have their eyes tested annually because eye problems usually develop insidiously and without pain but can have serious consequences including blindness.

The primary aims when caring for people with visual impairment are maximizing independence and maintaining safety. During childhood, specialized help is needed to support the family in achieving this (see Box 16.24, p. 448). Communicating and maintaining a safe environment are therefore the most important activities that the nurse needs to consider.

[Based on Wong et al (2001)]

Promoting development in children with sight impairment

Aims

Communication

Good verbal communication skills are essential and it is important to use normal speech and maintain eye contact when talking to visually impaired people, as the tone and inflexion convey much more than the actual words used (see Ch. 9). People with visual impairment often compensate by increased perception from their other senses. When approaching a visually impaired person this should be from the side of vision, if there is one. Calling their name will alert them to your approach and identifying yourself and others is essential. When leaving, tell them you are going. A call bell should be left at hand in care settings, as the visually impaired person cannot call to a passer-by for help unless they can hear them. The sense of touch is important for people with visual impairment, especially when this occurs together with hearing problems. Sighted people quickly scan their environment for cues about what is happening around them and the nurse must allow more time for visually impaired people to do this. When describing something being ‘over there’, a gesture that indicates location often accompanies the words. People with visual impairment may not see these gestures and therefore verbal cues about the location of items can cause confusion. Using more specific language, e.g. the television is beside the window, is helpful.

Written communication can pose challenges for people with sight impairment and simple interventions such as the use of a reading lamp directed towards the material will enhance residual vision, thus assisting reading. Spectacles should always be clean (see pp. 435–436). Many people with sight impairment can read ordinary print but find it is slow and very tiring while others find large print is essential. Books in large print are widely available. Hand-held magnifying glasses can be a useful reading aid. Large writing using a broad, black felt-tipped pen on white paper provides good contrast and is a useful strategy for providing written guidance to people with sight impairment.

Many people with sight impairment enjoy audio material. The RNIB provides a Talking Book Service and audiotapes that can be used in most cassette players are widely available. Headphones may be required to use audio equipment if others nearby are being distracted.

Some people with sight impairment use tactile forms of communication. Braille is a system of raised dots that can be learned by touch and produced using a Braillewriter. Moon is another, simpler form of tactile communication used mainly by older people. Both of these methods are effective but only between those people who can understand them.

An expanding range of technology is being designed to facilitate access to written material through increasing use of computers and the Internet.

Maintaining a safe environment

Many interventions will assist in maintaining a safe environment for everyone, especially for those with sight impairment (RNIB 2004b). Corridors and stairs should always be well lit, well signed and free from moveable and unnecessary items to minimize the occurrence of accidents. This is important at home, in care settings and in public places because many people, especially older people, have some degree of sight impairment although they may not be aware of it.

At home, a sight-impaired person can decide where items are kept and so find them again easily. Orientation to a new environment takes time. Most people will need to be accompanied around a new environment several times before becoming accustomed to new surroundings. Pot-pourri with different fragrances can be used to distinguish areas such as the sleeping area and sitting room. Sight-impaired people should be encouraged to explore parts of their new surroundings by touch. Moving personal belongings should only be carried out after discussion with the person.

Several issues may arise relating to safe use of medication (see Ch. 22). These include difficulty reading small print on labels of the containers, counting of tablets and opening blister packs. Assistance with administration of medication may be needed, especially those instilled into the eye.

People often find bright light and glare uncomfortable, both outdoors and inside on bright sunny days. Wearing ordinary sunglasses may not help because light also reaches the eyes from above and round the sides although a brimmed hat or baseball cap can solve the problem. Clip-on tinted spectacles with side shields that can be worn over normal spectacles are useful because they are quickly removed when going into a dark area.

Services and support

Local authorities maintain registers of blind and partially sighted people to enable planning of services to meet their needs. They provide home adaptations to meet individual needs.

After assessment, mobility aids may be provided to provide navigational independence. These include a white guide cane or, for some people, a guide dog.

The ear and hearing

The ear is a sensory organ that provides important information about the environment. It enables people to hear sounds that are interpreted by the brain. The ear is also the organ that enables people to maintain balance. The anatomy and physiology of hearing is outlined and the nursing interventions that will help a person with hearing impairment are explored.

The RNID (2004a) estimates there are 9 million deaf and hard of hearing people in the UK, with numbers increasing as the population becomes older. The incidence is about 2% in young adults rising to 55% in those over 60 years. Robins and Mangan (1999) highlight common and widespread difficulties faced by hearing-impaired people when communicating with nurses and most other health professionals.

Anatomy and physiology

The ear consists of three parts (Fig. 16.14):

Hearing

Sound waves entering the outer ear are funnelled along the external auditory canal to the eardrum which then vibrates. The vibrations are transmitted and amplified through the middle ear cavity by movement of the ossicles. When the vibrations reach the outer boundary of the inner ear, they generate fluid waves in the membranous cochlea and stimulate specialized receptors located in hair cells of the spiral organ (of Corti). This generates nerve impulses that are transmitted to the temporal lobe of the cerebral cortex where hearing is perceived.

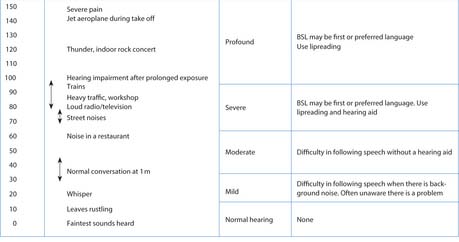

Assessment and prevention of hearing loss

Nurses play diverse roles is preventing hearing loss and assessment of people’s hearing.

Newborn babies have their hearing assessed through the use of sophisticated computer-linked equipment – otoacoustic emission testing (OAE) and/or automated auditory brainstem response test (AABR). Where this equipment is not available, health visitors perform a less reliable distraction test using simple sounds when the infant is between 6 and 8 months of age. Whenever a hearing problem is suspected, children have investigations that include audiometric testing (see below) and careful follow-up. Hearing impairment in children is often accompanied by developmental delay and difficulty with speech. Compliance with childhood immunization programmes is recommended as some infectious childhood diseases can cause deafness, e.g. mumps.