CHAPTER 28 Decision Making Related to Nonsurgical Periodontal Therapy

Differentiate among oral prophylaxis, nonsurgical periodontal therapy, and periodontal maintenance therapy.

Differentiate among oral prophylaxis, nonsurgical periodontal therapy, and periodontal maintenance therapy.BASIC CONCEPTS IN NONSURGICAL PERIODONTAL THERAPY

Nonsurgical periodontal therapy (NSPT) encompasses “plaque removal, plaque control, supragingival and subgingival scaling, root planing, and the adjunctive use of chemical agents.”1 Oral biofilm removal alone will not resolve inflammation in all cases. Supragingival biofilm control alone will not control all microorganisms in periodontal pockets. Therefore supragingival and subgingival biofilm control must occur simultaneously in therapy to enhance the outcome of NSPT (oral biofilm control is discussed in Chapters 15, 21, 22, 23, and 29).

Purposes of NSPT are as follows:

Scaling, instrumentation of the crown and root to remove oral biofilm, calculus, and stains, is used for the treatment of clients with healthy gingiva or gingivitis. Oral prophylaxis combines both supragingival and subgingival scaling with selective polishing. This procedure is preventive in nature and not therapeutic as is NSPT. The dental hygienist performs the oral prophylaxis when periodontal health or gingivitis is diagnosed. Root planing is a definitive procedure to remove cementum or surface dentin that is rough, impregnated with calculus, or contaminated with toxins or microorganisms. The objective of therapeutic scaling and root planing is to remove as little root structure as possible while returning adjacent tissues to health.

Periodontal debridement is the “removal of all subgingival plaque (oral biofilm) and its by-products (as evidenced by clinical signs of inflammation), clinically detectable biofilm retentive factors (calculus and overhangs), and detectable calculus-embedded cementum to finish the root surface during periodontal instrumentation while preserving as much tooth surface as possible.”2 This intervention blends scaling and root planing into one procedure (periodontal debridement) and focuses on all plaque retentive factors, not just calculus. Because oral biofilm is a primary causative factor for gingivitis and periodontitis, the emphasis on subgingival plaque removal is essential. Removal of calculus is secondary and important only because of its oral biofilm–retentive nature.

Periodontal debridement strives to achieve tissue healing with minimal iatrogenic damage (e.g., damage from professional treatment) to the soft tissue and cementum.

In addition to periodontal debridement, chemotherapeutic agents (via dentifrices, mouth rinses, or local controlled delivery or systemic antibiotics) are used to suppress infectious microorganisms and inflammation (see Chapters 23 and 29).

The therapeutic endpoint is the restoration of gingival health, reduction in pocket depth, and a gain in or maintenance of a stable clinical attachment level. These parameters can be expected only after a 4- to 6-week healing interval after NSPT. This appointment, called periodontal reevaluation, is scheduled to reassess the clinical parameters of health after NSPT. Without a reevaluation visit, the therapeutic endpoint of active therapy is never assessed or documented.

Assessment, Diagnosis, and Care Planning

For a discussion of periodontal assessment see Chapter 17. The periodontal diagnosis is determined after analyzing information collected during the assessment phase of therapy. The dental hygienist, and ultimately the dentist, must make an informed decision about the disease classification, extent, and severity. To accomplish this, the hygienist considers the following:

To classify periodontal diseases the practitioner differentiates between gingival disease and chronic or aggressive periodontitis. (See Chapter 17Box 17-3Box 17-5 for a complete review of the classifications of periodontal diseases and conditions.) Simultaneously clients may have areas of health and chronic periodontitis with slight, moderate, and advanced destruction.

Identification of disease includes overall disease severity and disease activity, as follows:

Disease severity is the measure of the destruction that occurred before the assessment. An important determination is whether the periodontitis is a slowly progressing form, such as chronic periodontitis, or rapidly progressing, such as aggressive periodontitis. This determination is critical in planning the course of nonsurgical care and predicting the prognosis. The clinician considers multiple factors when classifying disease, and it might not be possible to determine all these factors. For example, rate of disease progression can be determined only after multiple periodontal examinations are performed. Therefore initial diagnosis may be altered over time as more data become available. For this reason the clinical assessment results in a preliminary or presumptive diagnosis during initial or active therapy. A final dental diagnosis is the result of clinical findings and the response to nonsurgical or surgical care at the reevaluation visit. The dental diagnosis might change over time as periodontal maintenance occurs at appropriate time intervals.

Disease severity is the measure of the destruction that occurred before the assessment. An important determination is whether the periodontitis is a slowly progressing form, such as chronic periodontitis, or rapidly progressing, such as aggressive periodontitis. This determination is critical in planning the course of nonsurgical care and predicting the prognosis. The clinician considers multiple factors when classifying disease, and it might not be possible to determine all these factors. For example, rate of disease progression can be determined only after multiple periodontal examinations are performed. Therefore initial diagnosis may be altered over time as more data become available. For this reason the clinical assessment results in a preliminary or presumptive diagnosis during initial or active therapy. A final dental diagnosis is the result of clinical findings and the response to nonsurgical or surgical care at the reevaluation visit. The dental diagnosis might change over time as periodontal maintenance occurs at appropriate time intervals. Disease activity, more difficult to establish than disease severity, refers to the bone or attachment loss that is ongoing at the time of the examination. Periodontal disease activity involves periods of quiescence (inactivity) and periods of exacerbation (activity) evident in active disease. Periods of quiescence are characterized by a reduced host inflammatory response and little or no loss of bone and connective tissue attachment.

Disease activity, more difficult to establish than disease severity, refers to the bone or attachment loss that is ongoing at the time of the examination. Periodontal disease activity involves periods of quiescence (inactivity) and periods of exacerbation (activity) evident in active disease. Periods of quiescence are characterized by a reduced host inflammatory response and little or no loss of bone and connective tissue attachment.Unattached oral biofilm and anaerobic bacteria (gram-negative, motile) initiate periods of exacerbation that, in conjunction with other risk factors and the host’s response, result in loss of bone and connective tissue attachment, creating deeper periodontal pockets.

Periods of exacerbation might last for days, weeks, or months, and eventually quiescence may follow. This description of activity and inactivity explains the episodic nature of periodontal diseases. Clinically, disease activity can be measured only retrospectively by comparing the current examination findings with previous data. Therefore disease activity routinely is assessed at continued-care appointments by closely monitoring and recording probing depths, bleeding on probing, and clinical attachment measurements.

Periodontal diagnosis is different from, yet related to, the dental hygiene diagnosis. NSPT relates to a variety of unmet human needs, but the clinical parameters of periodontal disease focus on the human need for skin and mucous membrane integrity of the head and neck. Bleeding, gingival inflammation, pocket depth, and attachment loss are all deficits related to this need, and each requires interventions, such as NSPT.

Sequencing of therapeutic procedures follows a traditional model of periodontal care planning involving four phases of periodontal care (see Chapter 20, Table 20-1). NSPT is part of phase I therapy (referred to as initial therapy, initial preparation, or antiinfective therapy). Much of phase I therapy is the responsibility of the dental hygienist working in concert with the general dentist or periodontist. Active therapy is either nonsurgical or surgical care or both, depending on the needs of the client. Active therapy includes phase I care and can also extend to phase II care. Phase III involves restorative care.

After a series of appointments for NSPT (and surgery, if indicated), the client is moved from active therapy to maintenance therapy. Periodontal maintenance (PM), also known as supportive periodontal therapy, periodontal recare, or continued-care, is phase IV care, an extension of periodontal therapy performed at selected intervals to assist the client in maintaining oral health. It continues at client-dependent intervals for the life of the dentition or its implant replacements. PM may be discontinued and active therapy reinstituted if recurrent disease is detected. Periodontal disease states that are refractory are indications for bacterial culturing and subsequent antibiotic therapy in addition to mechanical periodontal debridement. Refractory refers to periodontal disease states that continue to progress despite client compliance with recommended oral self-care and professional care that yields successful clinical outcomes for most clients. Care planning approaches to periodontal therapy vary by the following:

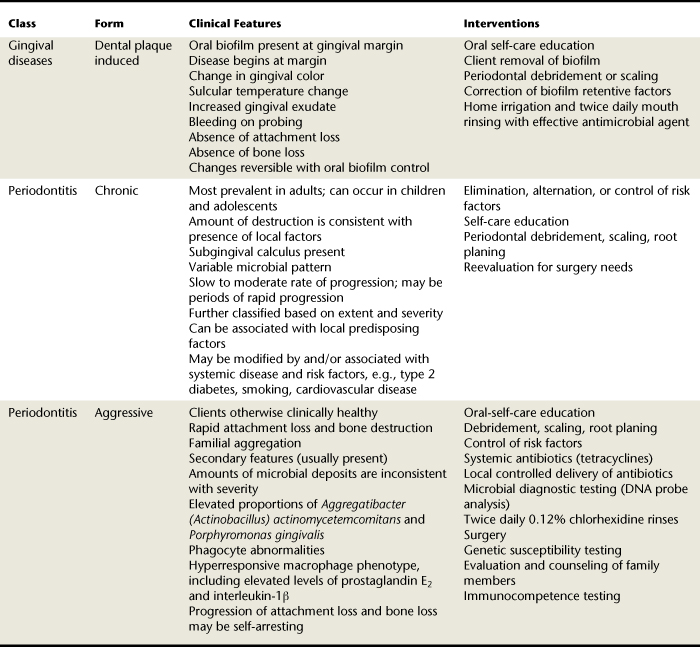

In planning care, interventions are decided on and scheduled (see Chapter 20). The number, sequence, and length of appointments are determined to best meet the client’s human needs. Table 28-1 is not intended to be all inclusive, but instead outlines common periodontal disease features and treatment options and emphasizes where surgical intervention might be needed.

TABLE 28-1 Clinical Features and Interventions for Common Classifications of Periodontal Diseases (see Chapter 17)

Chronic Disease States3-6

Chronic disease states (see Chapter 17Box 17-3Box 17-4Box 17-5) of dental plaque–induced gingivitis and periodontitis progress slowly and respond in a relatively predictable manner to NSPT directed at reducing disease-causing bacteria. For chronic disease states the main focus of NSPT is oral self-care education and mechanical removal of oral biofilm and biofilm retentive factors to reduce microbial load and the host’s hyperinflammatory response. (Note that it is the chronic hyperinflammatory response of the host that is responsible for destruction of collagen and bone.) Oral self-care is ultimately the client’s responsibility; instrumentation and selective polishing are the professional’s responsibility.

Therapy for gingivitis includes oral self-care education and supragingival and subgingival debridement (scaling), along with antimicrobial and antiplaque agents. Correction of plaque retentive factors also is essential, including overhanging margins, open margins, overcontoured crowns, narrow embrasure spaces, open contacts, ill-fitting fixed or removable partial dentures, dental caries, and tooth malposition. Infrequently, surgical correction of gingival deformities that hinder the client’s oral self-care is needed to aid in control of oral biofilm. After phase I active therapy, the client’s condition is reevaluated to determine future care.

Therapy for chronic periodontitis with slight to moderate loss of periodontal support includes active therapy and PM. Systemic diseases and other risk factors must be considered in the care plan because of their effect on the therapeutic outcome of NSPT (e.g., diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease, human immunodeficiency virus [HIV] infection and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome [AIDS], pregnancy, smoking, substance abuse, and medications [see Chapters 12, 17, and 18]). When systemic conditions are present, consultation with the client’s physician(s) is appropriate. Oral self-care and periodontal debridement are the main therapeutic foci and are crucial to a successful long-term clinical outcome. Antimicrobial agents or devices might be useful when treating periodontitis with coexisting gingivitis. Implant therapy can be initiated during the initial phase of care or considered as phase II therapy.

Periodontal surgery is also a problem-focused therapy aimed at enhancing root debridement and tissue regeneration and reducing gingival recession for clients who have effective self-care practices. Surgery might be indicated for advanced periodontal sites; however, most cases of slight and moderate involvement can be treated nonsurgically, provided access to subgingival deposits and plaque retentive factors is achievable. If the results of initial therapy resolve the periodontal infection and conditions, then PM is scheduled. If results of initial therapy do not resolve the periodontal condition, then surgery is considered and referral to a periodontist is indicated (see section on periodontal surgery later in this chapter).

When advanced chronic periodontitis is present, additional considerations for therapy are necessary and include subgingival microbial analysis, antibiotic sensitivity testing, and extraction of hopeless teeth. In some cases optimal results may not be attainable because of the client’s health, age, systemic condition, and extent of disease; initial therapy might be the endpoint of periodontal care.

Aggressive Disease States7

Aggressive periodontitis and some uncommon forms of gingivitis will not respond predictably to NSPT. Aggressive periodontitis is seen in clients who otherwise appear healthy, tends to have a familial aggregation, and progresses rapidly. Traditional NSPT is the basic therapeutic modality for aggressive periodontitis; however, quantity of oral biofilm and calculus deposits is less important than the host’s inflammatory and immune response to specific periodontal pathogens present. Initial periodontal therapy alone often is not effective at controlling host response to specific pathogens. Other care planning considerations include the following:

Tooth extraction and occlusal therapy might also be part of therapy. The PM interval should be short (1 to 3 months) to slow rapid disease progression. Diagnosis of aggressive periodontitis might occur after active therapy, reevaluation, and several intervals of PM; at this point, referral to the periodontist is indicated.

Appointment Planning (see Chapter 20)

One major consideration that affects the appointment plan during NSPT is the use of pain control strategies (see Chapters 37, 39, and 40). Need must be established based on assessment data and client-related factors. Pain control modalities might require more appointment time, and this should be included in the care plan. Length of appointment could vary from 40 to 90 minutes depending on client needs (Table 28-2).

TABLE 28-2 Determining Need for Local Anesthetic Agents∗

| Factor | Comment |

|---|---|

| Periodontal Assessment Factors | |

| Pocket depth >4 mm | Limited accessibility and visibility decrease chance of complete deposit removal; pain control increases client comfort and operator confidence |

| Tissue tone | Tight or nonelastic tissue may limit access to deep pockets or challenging root anatomy Local anesthetic may be used to increase the turgor of the gingiva if injected into an edematous interdental papilla |

| Pocket topography | Cratering at epithelial attachment or narrow intrabony pockets; pain control enhances deposit removal |

| Furcations | Limited accessibility and visibility decreases chance of complete deposit removal; pain control increases client comfort and operator confidence |

| Root anatomy | |

| Inflammation | |

| Hemorrhage | Use vasoconstrictor when hemostasis is a concern such as with bleeding on probing or spontaneous hemorrhage |

| Client-Related Factors | |

| Pain threshold | If pain threshold is low, administer local anesthetic agent to control pain and/or reduce anxiety level |

| Sensitivity | |

∗ Always assess health, dental, and pharmacologic histories before the selection and use of pain control agents.

From Hodges KO: Concepts in nonsurgical periodontal therapy, Albany, NY, 1998, Delmar.

Case Presentation and Informed Consent (see Chapter 20)

Objectives of a case presentation are to do the following:

Through case presentation and gaining informed consent, the clinician is able to communicate to the client the following:

IMPLEMENTATION OF NONSURGICAL PERIODONTAL THERAPY

Implementation includes the delivery of preventive and therapeutic procedures identified in the individualized care plan to meet client human needs. Preventive and therapeutic entities of NSPT such as self-care education, manual and mechanized instrumentation, pharmacotherapeutic interventions, pain control strategies, if indicated, and selective polishing are performed. Supportive interventions in achieving the ultimate goals of NSPT are overhang removal (margination), desensitization, dietary assessment and counseling, dental caries management, and occlusal therapy. Therapeutic procedures include the following:

Mechanical nonsurgical pocket therapy: scaling and root planing (periodontal debridement) using hand-activated and/or mechanized instruments

Mechanical nonsurgical pocket therapy: scaling and root planing (periodontal debridement) using hand-activated and/or mechanized instruments Pharmacotherapeutic nonsurgical pocket therapy: use of systemic, topical, and controlled delivery antimicrobial agents to selectively remove or inhibit pathogenic bacteria (also known as antimicrobial therapy or periodontal chemotherapy) (see Chapter 29).

Pharmacotherapeutic nonsurgical pocket therapy: use of systemic, topical, and controlled delivery antimicrobial agents to selectively remove or inhibit pathogenic bacteria (also known as antimicrobial therapy or periodontal chemotherapy) (see Chapter 29).Proposed as a treatment strategy, full-mouth disinfection is the scaling and root planing of all pockets within a 24-hour time period, including the application of 0.12% chlorhexidine gluconate to all periodontal pockets followed by twice-daily 30-second mouth rinsing with 0.12% chlorhexidine gluconate for 2 months.8 The rationale underlying this intervention is that the traditional method of four consecutive appointments for scaling and root planing without proper disinfection might permit reinfection of previously disinfected pockets by pathogenic bacteria from an untreated region of the mouth. A practical limitation of full-mouth disinfection is appointment scheduling in a practice setting.

Mechanical Nonsurgical Pocket Therapy (Advanced Hand-Activated Instrumentation)

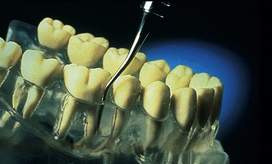

“The critical determinant of periodontal therapy is not the choice of treatment modality, but the detailed thoroughness of the root surface debridement and the patient’s standard of oral hygiene care.”9 Advanced hand-activated instrumentation is an extension of basic instrumentation. Instrumentation in pockets ≥6 mm in and adjacent to furcations and where mobility exists is significantly impaired when providing NSPT; therefore subsequent periodontal surgery should be considered. Options for treating areas affected by periodontal disease include traditional armamentarium such as files, universal curets, and area-specific curets (see Chapter 24), as well as debridement curets, furcation curets, and diamond-coated periodontal instruments. The clinician selects these instruments based on the following:

A single instrument is not likely to produce the desired clinical and therapeutic endpoints because multiple clinical factors require a variety of periodontal debridement instruments. For example, during initial therapy the clinician might encounter generalized heavy, tenacious subgingival deposits requiring removal with files and standard unmodified ultrasonic inserts. Both universal and area-specific hand-activated instruments are then used to debride because the clinician is treating most root surfaces of most teeth. Universal instruments enable the clinician to treat the midline of proximal areas of the tooth and adapt as far subgingivally as is reasonable, depending on the tissue tone and pocket topography. The final periodontal debridement is accomplished with area-specific instruments with flexible shanks as well as mechanized instruments with precision thin tips to remove oral biofilm, extrinsic tooth stain, calculus deposits, and root toxins to create a healthy root environment (see Chapter 24).

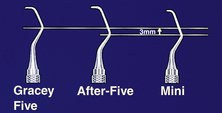

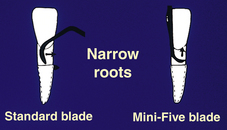

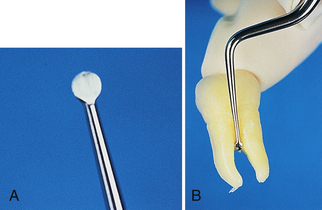

Options for hand-activated instrumentation in pockets ≥5 mm include extended shank curets and minibladed curets. Extended shank curets have a terminal shank that is 3 mm longer than the standard area-specific curet to access deep periodontal pockets and improve oral clearance around the crown (Figure 28-1). The blade itself is also thin to enhance insertion and reduce tissue distention (Figure 28-2).

Figure 28-1 Gracey family of curets: Gracey (standard area-specific design), After-Five (extended shank area-specific design), and Mini-Five (minibladed area-specific design).

(Courtesy Hu-Friedy, Chicago, Illinois.)

Figure 28-2 After-Five root planing curet. Adapting to the root in a deep periodontal pocket.

(Courtesy Hu-Friedy, Chicago, Illinois.)

Minibladed curets combine features of the extended shank designs with a 50% reduction in blade length as compared with the extended shank or standard design (see Figure 28-1). Minibladed curets enhance adaptation on narrow facial and lingual surfaces of anterior teeth (Figure 28-3), in furcations, and on root surfaces in narrow and deep periodontal pockets. A limitation of minibladed curets is the extension to the midline of proximal surfaces. Also, because of the small size of the blade, their longevity after sharpening is reduced when compared with other instruments. Both the extended shank and minibladed versions are available in any area-specific pattern except the 9/10 and 17/18 (Hu-Friedy, Chicago, Illinois). The 9/10 and 17/18 designs both have accentuated shank bends and long terminal shanks, enhancing their use in deeper pockets and difficult-to-reach areas without the extended shank feature (see Procedure 28-1 for use of extended and minibladed curets).

Figure 28-3 Mini-Five applications: narrow roots. The short blade of the minibladed design permits access to the epithelial attachment on the facial surface without the use of the toe-down approach.

(Courtesy Hu-Friedy, Chicago, Illinois.)

Procedure 28-1 USE OF EXTENDED SHANK AND MINIBLADED CURETS

EQUIPMENT

STEPS

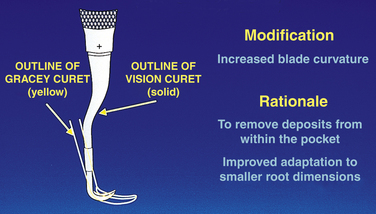

Other area-specific instruments include Vision Curvettes (Hu-Friedy, Chicago, Illinois), which have curved blades and are 50% shorter than the standard design. The shank has 5-mm and 10-mm marks for visual cues to pocket depth during instrument use. Curvature of the blade is what distinguishes this set of instruments from minibladed curets (Figure 28-4). Curvettes, designed to enhance adaptation on teeth with deep periodontal pockets, have four configurations:

Subzero with a long shank for instrumentation on the facial and lingual surfaces and around line angles on premolars and anterior teeth

Subzero with a long shank for instrumentation on the facial and lingual surfaces and around line angles on premolars and anterior teethA disadvantage of Vision Curvettes is the short working end, which limits extension to the midline of proximal surfaces, and the upward curvature of the blade, which could cause root gouging or striations in the root if not adapted properly.

Debridement curets are designed for gentle removal of residual deposits and for smoothing root surfaces after ultrasonic instrumentation (Figure 28-5). They are ideal for furcations, developmental grooves, and line angles. The entire edge of the blade is a cutting edge, which enables the clinician to use a vertical, horizontal, or oblique push or pull stroke.

Figure 28-5 A, Debridement curet. In a close-up view the instrument blade appears similar to a small spoon excavator. The entire circumference of the blade is a cutting edge. B, Debridement curet (SOH 1/2) in furcation. The small disk-shaped blade curves into the tooth, easily adapting to the furcations. The long terminal shank (15 mm in length) facilitates access to deep and narrow periodontal pockets.

(Courtesy Hu-Friedy, Chicago, Illinois.)

Furcation curets are designed for root concavities and for furcation instrumentation. The blade width is perhaps less than that of other curets, ranging from 1.3 mm to 0.9 mm.

Diamond-coated files (Brasseler, G. Hartzell & Son, and Hu-Friedy) are instruments that resemble a Nabers probe in appearance and have a diamond coating on the end that is used against deposit. They are best used with endoscopic therapy on minute pieces of calculus that are magnified for the clinician for final debriding and polishing of root surfaces and furcations. Diamond-coated files must be used directly on calculus with light pressure so as not to cause overinstrumentation and its consequences including rough root surface and/or sensitivity. Benefits are enhanced efficiency and enhanced access especially in small narrow pockets, at line angles, and in developmental grooves.

Furcation Involvement (see Chapter 17)

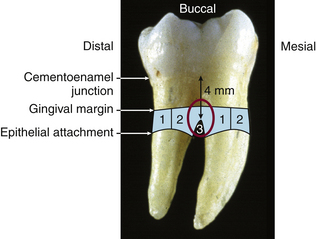

Presence of furcation involvement seriously compromises the prognosis of the tooth; therefore detection and thorough periodontal debridement are essential at the earliest point in NSPT. Furcation involvement should be suspected in the presence of a 4-mm periodontal probe reading that is recorded on a multirooted tooth adjacent to a buccal or lingual furcation. In some cases, especially in mandibular molars where the bifurcation is located only 3 mm from the cervical line, invasion can occur in the early stages of periodontitis with attachment loss of only 2 to 4 mm.

Furcation entrance diameters are relatively small; therefore access with an explorer, a Nabers probe, and especially a curet is challenging. The estimated furcation entrance width of maxillary first molars is from 0.5 mm to 0.75 mm, depending on the surface. The average width of the furcation entrance on a mandibular molar buccal surface is 0.75 mm; lingual width is 1 mm.

The blade face width of curets is from 0.75 mm to 1 mm. Area-specific curets (Gracey), however, are slightly narrower in blade width than are universal designs. Curets that have been sharpened, creating a thinner blade, mini-extended curets, and diamond-coated files are recommended for furcation debridement. A comparison of curet blade width to the furcation entrance width demonstrates the difficulty in adequately debriding these areas without surgery. The clinician refers to the degree of invasion of the furcation to aid in instrument selection and instrumentation.

Location of furcation involvement, relationship of the gingiva and furcation entrance, and pocket depth also are considered when deciding how to instrument the area. The best approach is to treat each root as a separate tooth, when access permits, using a combination of strokes. The distal surface of each root is instrumented first, the buccal and lingual surfaces next, and last, the mesial surfaces. The clinician overlaps strokes, especially in the concavity where the roots meet (Figure 28-6). Next, the concavity coronal to the furcation entrance is instrumented by employing horizontal and oblique strokes with a toe-down approach, if applicable. An area-specific curet designed for mesial surfaces such as the 11/12 Gracey or one with a straight shank such as the 7/8 Gracey can be used in the concavity.

Figure 28-6 Periodontal debridement of a furcation. The distal surface of each root is instrumented (area 1). The buccal, lingual, and mesial surfaces are then treated (area 2). Last, the concavity is debrided (area 3).

The clinician may not be able to treat each root separately if the gingiva occludes the furcation, the pocket depth is shallow, or the furcation entrance is barely detectable. Instead the area is treated with a combination of strokes, including the toe-down approach. The minibladed or micro-minibladed curet is especially appropriate for these situations.

Maxillary mesial and distal furcations present a unique challenge.

Access to the mesial furcation is best from the lingual surface because the furcation is located lingually and not in the midline. An extended shank, area-specific, mesial surface design and a universal design with a long terminal shank might be used in combination to treat this area.

Access to the mesial furcation is best from the lingual surface because the furcation is located lingually and not in the midline. An extended shank, area-specific, mesial surface design and a universal design with a long terminal shank might be used in combination to treat this area. The distal furcation entrance is located near the midline of the proximal surface; therefore access from the lingual or buccal surface is equal.

The distal furcation entrance is located near the midline of the proximal surface; therefore access from the lingual or buccal surface is equal. Proximal surfaces of maxillary teeth require extreme rolling and pivoting to adapt explorers and curets into the furcation defect. Alternative fulcrum placement such as finger-on-finger, opposite arch, and cross-arch placement might be useful to negotiate the furcation (see Chapter 24).

Proximal surfaces of maxillary teeth require extreme rolling and pivoting to adapt explorers and curets into the furcation defect. Alternative fulcrum placement such as finger-on-finger, opposite arch, and cross-arch placement might be useful to negotiate the furcation (see Chapter 24).Mobility (see Chapter 17)

Mobile teeth interfere with optimal fulcrum placement; therefore problem solving is indicated. The finger-on-finger rest, in which the fulcrum is established on the index finger or thumb of the nonoperating hand, is especially useful in this situation. Also, periodontal debridement of a tooth adjacent to a mobile tooth is challenging because the mobile tooth would usually be used for the fulcrum placement. Again, alternative fulcrums are used, such as a conventional fulcrum placed farther away from the tooth being treated, or an opposite arch or cross-arch approach is used (see Chapter 24).

CLINICAL OUTCOMES OF PERIODONTAL DEBRIDEMENT9,10

Despite incomplete calculus and endotoxin removal, nonsurgical instrumentation usually arrests periodontitis (i.e., the host can now manage the microbial challenge). After scaling and root planing, a loss of clinical attachment at sites with initially shallow pockets and a gain in attachment level at sites with deeper pockets are common. Loss in attachment at shallow sites is thought to relate to overinstrumentation and overzealous self-care. Also, the buccolingual gingival thickness (thin gingival walls) experiences more loss, and instrumentation at deeper sites adjacent to shallow sites damages the shallow sites.

Shallow sites (1 to 3 mm) have been shown to have a mean clinical attachment level change of −0.34 mm. Pockets with initial depth of 4 to 6 mm had an attachment level gain of 0.55 mm. Pockets 7 mm or greater had an attachment gain of 1.29 mm. Clinical attachment level gain from mechanical therapy is 2.9 mm and for surgical methods is 4.2 mm. Mean probing depth reduction for 4- to 6-mm sites was 1.29 mm versus 2.16 mm for sites ≥7 mm. Pocket depth reduction is greater after surgery than after scaling and root planing; however, over time the differences become insignificant. These findings highlight the need for clinicians and clients to understand the expected outcome of mechanical therapy during NSPT, the need for continued care at appropriate PM intervals, and the potential for additional treatment.

Clinicians have used bleeding on probing as an indicator of disease activity. There is a lack of correlation between bleeding on probing and risk for future clinical attachment loss; therefore absence of bleeding is used as a criterion for stability. Mechanical NSPT predictably reduces the level of inflammation and hence the high levels of proinflammatory mediators (cytokines and prostaglandins) that cause breakdown of bone and collagen. After scaling and root planing several outcomes are expected10:

Microbes that repopulate the subgingival environment after therapy come from incomplete instrumentation, and/or growth of supragingival oral biofilm into the pocket.

Microbes that repopulate the subgingival environment after therapy come from incomplete instrumentation, and/or growth of supragingival oral biofilm into the pocket. Predictable elimination of Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans associated with aggressive disease does not occur. Likewise, Porphyromonas gingivalis is not eradicated because both subgingival bacteria invade the adjacent periodontal tissues.

Predictable elimination of Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans associated with aggressive disease does not occur. Likewise, Porphyromonas gingivalis is not eradicated because both subgingival bacteria invade the adjacent periodontal tissues. Subgingival therapy does not significantly affect other areas that might be a source for reemerging periodontal bacteria such as the tongue and tonsillar area.

Subgingival therapy does not significantly affect other areas that might be a source for reemerging periodontal bacteria such as the tongue and tonsillar area. Microbial repopulation of subgingival pockets can be inhibited by effective oral self-care practices. Presence of supragingival oral biofilm facilitates repopulation of pockets with high percentages of spirochetes and motile rods within 4 to 8 weeks.

Microbial repopulation of subgingival pockets can be inhibited by effective oral self-care practices. Presence of supragingival oral biofilm facilitates repopulation of pockets with high percentages of spirochetes and motile rods within 4 to 8 weeks. Shifts to health subgingivally are transient; therefore PM at timely intervals is needed to sustain positive effects.

Shifts to health subgingivally are transient; therefore PM at timely intervals is needed to sustain positive effects. Hand-activated, ultrasonic, and sonic instrumentation all produce similar clinical and microbiologic results.

Hand-activated, ultrasonic, and sonic instrumentation all produce similar clinical and microbiologic results.As previously discussed, furcations associated with periodontitis present a particularly challenging environment to accomplish the objectives of mechanical therapy. Research suggests9 that 19% to 57% of teeth diagnosed with furcation involvement were lost over a 15-year period as compared with 5% to 10% of teeth without furcation involvement that were lost during the same period of time. Typically, problems with mechanical therapy adjacent to furcation involvement include the following:

The same factors affect the clients’ ability to perform oral self-care.

Aggressive instrumentation to remove endotoxin is unwarranted because endotoxin is loosely bound to the root surface. Also, treated root surfaces become recontaminated over short periods of time. Another outcome of mechanical instrumentation to consider is the role root surface roughness plays in microbial recolonization and in achieving the desired clinical endpoint. Both surface free energy and roughness play major roles in the initial adhesion and retention of microbes. These findings are particularly true with regard to supragingival root surfaces; however, they are also important to subgingival root surfaces. Clinicians need to achieve the smoothest root surface possible without resorting to overinstrumentation.

Clinical and Therapeutic Endpoints

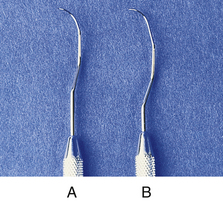

Clinical endpoint measures tooth surfaces’ preparation for healing of adjacent tissues. It is determined immediately after periodontal therapy by exploring the subgingival environment. To assess the clinical endpoint, a variety of explorers may be used, accompanied by air and illumination:

The 11/12 extended shank design is particularly useful in NSPT. Like the extended shank curets, it has a longer terminal shank (3 mm) when compared with the standard design. The 11/12 design is indicated for deep pockets and anterior teeth. A limitation might be midline extension on posterior proximal surfaces owing to the short working end (Figure 28-7).

Figure 28-7 11/12 Explorers for use in nonsurgical periodontal therapy. A, Standard design. B, Extended shank.

(Courtesy Hu-Friedy, Chicago, Illinois.)

The therapeutic endpoint of therapy determined at the evaluation visit includes the measurement of critical criteria such as probing depth, clinical attachment level, and gingival inflammation accompanied by bleeding. If bleeding and inflammation are present, site-specific therapy is performed including instrumentation, consideration of chemotherapeutic agents, and further client education in self-care practices. Evaluation is the only mechanism for determining if inflammation has been eliminated, as evidenced by the absence of bleeding and swelling and whether the level of attachment is maintained. If the clinical endpoint yields the desired therapeutic endpoint, then the appropriate level of calculus and/or cementum removal and removal of biofilm retentive factors has been attained.

The dental hygiene practitioner is constantly evaluating the clinical endpoint of instrumentation during NSPT to determine if it is sufficient. The topography of the tooth surface is the best criterion to make this decision, because removal of subgingival oral biofilm and its byproducts cannot be measured clinically. The clinical endpoint for the majority of clients is a tooth surface devoid of detectable biofilm retentive factors. If subgingival problems remain, the clinician should attempt to remove root roughness. When deciding if instrumentation is complete, the clinician considers the following:

If the clinician is in doubt about certain areas, these sites should be recorded in the record of services to ensure their evaluation at the next visit during active therapy, or at the reevaluation visit. Endoscopic therapy is used to reassess difficult and refractory areas (see Chapter 24).

When instrumentation technique is sound and further instrumentation is not changing root roughness and irregularity, then the clinician stops instrumentation. The area is reexamined at the evaluation visit to assess if the clinical endpoint was appropriate. If the area warrants further instrumentation because of persistent inflammation or bleeding, then instrumentation continues. This decision-making process and evaluation build the clinician’s experience base and expertise in providing NSPT. Also, the clinician must recognize the client’s response in the healing process; therefore client systemic health and self-care must be evaluated with other clinical parameters.

It is important to note that the basic definition of periodontal debridement includes the removal of all oral biofilm retentive factors, including removal of detectable calculus, and that the therapeutic endpoint of periodontal debridement is periodontal health. Removal of 100% of calculus and diseased cementum is not possible or even desirable because of tooth structure loss and probable dentinal hypersensitivity. Although meticulous periodontal debridement may remove some cementum, aggressive root planing to intentionally remove cementum is not recommended.

In contrast, periodontal debridement requires complete removal of clinically detectable calculus. Calculus removal is critical to the success of periodontal therapy because calculus retains oral biofilm. Also, there will probably never be one simple standard for assessing the clinical endpoint because the client’s systemic health, immune response, and self-care practices influence healing. Sound professional judgment must be practiced to determine endpoints of NSPT. Intentionally leaving detectable calculus, therefore, constitutes unethical or substandard care.

Evaluation

Final evaluation compares the initial assessment data with client data at the completion of care to determine if therapeutic and client goals were met. The clinician, however, evaluates care continually throughout the implementation phase of NSPT. Because of the extent of therapy and the multiple visits involved, the clinician has the opportunity to reexamine areas previously treated to assess gingival healing via color change and shape, deposit removal, the client’s oral self-care practices, and/or results from diagnostic testing or medical screening. Generally the first evaluation of the gingival healing takes place 2 weeks after completion of periodontal debridement of a sextant, quadrant, or half-mouth. This 2-week period represents the time required for epithelial adaptation. Assessment of oral biofilm retentive factors also occurs at the next appointment after each segment of periodontal debridement is completed. The care plan is revised to include this new information and to assess client needs.

Evaluation encompasses the reevaluation visit 4 to 6 weeks after initial or active therapy. The purpose of reevaluation is to do the following:

The reevaluation visit includes the following:

Reassessing initial periodontal and risk factor assessment to evaluate host response and self-care practices

Reassessing initial periodontal and risk factor assessment to evaluate host response and self-care practicesSee Box 28-1 for a reevaluation sequence that can be used in practice.

BOX 28-1 Reevaluation Appointment Guide

Assessment

Clients who were initially diagnosed with plaque-induced gingival disease should demonstrate a reduction in gingival inflammation, stability of clinical attachment levels, and a reduction in clinically detectable oral biofilm to a level compatible with gingival health. Client factors reassessed if resolution of conditions does not occur are as follows:

The expected outcome for clients who were initially diagnosed with chronic periodontitis is a reduction in the following:

If nonresponse is apparent, evaluation of the site(s) or the case is imperative.

Nonresponse does not necessarily imply an aggressive disease state. Retreatment should occur, and another PM visit can be arranged at the appropriate interval. For clients with aggressive periodontitis, stability and control of the disease are the objectives of reevaluation. If control is not possible, then slowing the progression of disease is the next alternative. Inclusion of reevaluation in a care plan is dependent on multiple factors that are assessed during initial therapy (Box 28-2).

Each client who has completed initial or active NSPT should be reevaluated to assess if the objectives of NSPT were met. It is critical that individuals with systemic conditions, risk factors, aggressive forms of the disease, pockets ≥5 mm, advanced bone loss or attachment loss, furcations, and/or mobility are evaluated. Compliance on the part of the client seems to be better when the reevaluation visit is presented as an essential part of the NSPT care plan. The clinician must believe that reevaluation is an integral part of each care plan to successfully explain the need for reevaluation to the client. Some practices consider the evaluation visit part of the initial periodontal debridement (scaling and root planing) fee; other practices believe the reevaluation visit warrants a separate fee.

In practice a reevaluation appointment is typically scheduled for 30 minutes, depending on the services included in the care plan. Reappointment for retreatment is indicated if more than 30 minutes is needed. For example, a client returns with unresponsive areas adjacent to furcations with 5- to 6-mm pocket depth. Nonresponse is identified as a new problem, and another appointment is scheduled.

Explanations for the nonresponse focus on the potential reasons for the lack of healing, including incomplete periodontal debridement, systemic disease, inadequate self-care, smoking, or use of inappropriate self-care aids. More than one course of action will be chosen to address the nonresponse. The clinician could retreat the area with extended shank curets and/or ultrasonic instrumentation, reevaluate the self-care aid(s) recommended or used, reeducate, and/or use an antimicrobial agent (professional irrigation coupled with home irrigation, or local delivery) in the area. These additional therapies will precipitate the need for more discussion and client decision making (informed consent).

At the conclusion of the reevaluation visit, the first PM visit is established as follows:

8 to 10 weeks from the reevaluation visit if the objectives of care are reached. This represents an interval of 3 or 4 months after the last appointment for periodontal debridement.

8 to 10 weeks from the reevaluation visit if the objectives of care are reached. This represents an interval of 3 or 4 months after the last appointment for periodontal debridement. 4 weeks from the last appointment when periodontal debridement was performed, if the objectives of care are not reached or if multiple risk factors for continuing periodontal destruction exist. If the objectives of care are not reached and the preliminary diagnosis is mild to moderate periodontitis, then the client is returned to the initial therapy phase of care versus maintenance. Table 28-3 offers suggested PM intervals.

4 weeks from the last appointment when periodontal debridement was performed, if the objectives of care are not reached or if multiple risk factors for continuing periodontal destruction exist. If the objectives of care are not reached and the preliminary diagnosis is mild to moderate periodontitis, then the client is returned to the initial therapy phase of care versus maintenance. Table 28-3 offers suggested PM intervals.TABLE 28-3 Suggested Periodontal Maintenance Therapy Intervals

| Characteristics | Interval |

|---|---|

| First-year client; routine therapy and uneventful healing | 3 months |

| First-year client; difficult case with complicated prosthesis, furcation involvement, poor crown-to-root ratios, questionable client cooperation | 1-2 months |

| Excellent results well-maintained for 1 year or more | 6 months–1 year |

| Client displays good oral self-care, minimal calculus, no occlusal problems, no complicated prostheses, no remaining pockets, and no teeth with less than 50% of alveolar bone remaining | 6 months–1 year |

| Generally good results maintained reasonably well for 1 year or more, but client displays some of the following: | 3-4 months (select interval based on number and severity of negative factors) |

| Generally poor results after periodontal therapy and/or client displays some of the following: | 1-3 months (select interval based on number and severity of negative factors; consider re-treating some areas or extracting severely involved teeth) |

Adapted from Newman MG, Takei HH, Klokkevold PR, Carranza FA: Carranza’s clinical periodontology, ed 10, St Louis, 2006, Saunders.

Referral to a Periodontist

The decision to care for the client in the general dental practice or to refer to a periodontal practice is based on the following:

For example, if the periodontal diagnosis is advanced periodontitis or an aggressive form of the disease, referral to a periodontist is indicated. A client with moderate chronic periodontitis might also be referred to the periodontist if risk factors exist and the extent of disease is close to an advanced disease status. Some practitioners use the “5-mm standard” as a factor when referring, meaning that a loss of attachment of 5 mm represents loss of bone support of about one half of the root length of the average tooth. It is then the responsibility of the general practitioner to strive to maintain periodontal health and inform the client when that goal is not being achieved.

Some clients decline referral because of geographic constraints, cost, or the fact that they do not want to go to a new office setting. Documentation of the referral to the periodontist and the client’s response is imperative.

Most periodontists are willing to alternate visits for PM with the general practitioner. Clients with advanced chronic disease or aggressive disease will probably be maintained at the periodontist’s office and be referred to the general dentist once every 6 months or once a year for restorative examination, depending on the client’s caries risk.

Surgical Intervention

Some forms of moderate to advanced periodontitis need to be reevaluated often to determine if the goals for periodontal therapy are achieved and maintained. Therapeutic goals for these clients include the following:

Surgery should be considered when nonsurgical therapy is unsuccessful at reaching these goals. A surgical approach, as opposed to NSPT, is considered in the following circumstances:

NONSURGICAL PERIODONTAL THERAPY INSURANCE ISSUES (TABLE 28-4)

Dental benefit plans (dental insurance) influence the NSPT provided. The dental hygienist needs to know the following:

Who is responsible for filing insurance claims, explanations to the client, and communication with the insurance company

Who is responsible for filing insurance claims, explanations to the client, and communication with the insurance companyTABLE 28-4 Insurance Codes for Nonsurgical Periodontal Therapy

From American Dental Association (ADA): Current dental terminology 2007-2008, Chicago, 2008, ADA.

BOX 28-3 Common Dental Terms for Insurance Associated with Nonsurgical Periodontal Therapy

From American Dental Association (ADA): Current Dental Terminology 2007-2008, Chicago, 2008, ADA.

The dental hygienist is a source of information about insurance coverage for periodontal services. The dental hygienist may explain the relationship between the office fees and third-party insurance benefits and the responsibility of the client for the NSPT fee charged. Treatment plans are developed according to professional standards and client needs, not according to the provisions of the client’s insurance policy. This philosophy ensures that clients receive appropriate care.

When diagnosing and classifying periodontal disease for insurance claims, the clinician uses the following two considerations:

A specific periodontal diagnosis is used for insurance reporting whenever appropriate; an extensive range of therapies exists for periodontal therapy, and no one treatment is effective for everyone. In fact, one section of the mouth might require one type of therapy while another area requires a different therapy. Therefore description of disease in one quadrant of the mouth as reported on the insurance claim might differ from that in another area.

It is useful to develop a fee-for-service schedule for dental hygienists that includes the following:

This schedule provides standardized fees for service among dental hygienists in the same practice and enhances communication with the office manager. Although there are ADA codes for various supportive services (local anesthetic, root desensitization), not all dental plans provide reimbursements for these services. In fact, there is variation in insurance coverage by different carriers, as well as in different plans from the same carrier with regard to services covered, frequency of payment for services, and maximum fee reimbursed. For example, some insurance plans reimburse for PM every 3 months, and others do not. Computer practice management software programs aid the staff and dental hygienist in assessing reimbursement rates; however, the ultimate responsibility for the fee rests with the client.

PERIODONTAL MAINTENANCE11

PM is planned after the active phase of periodontal care at appropriately timed intervals based on client needs. Periodontal maintenance is the preferred term for what was formerly referred to as supportive periodontal therapy or periodontal recall. Although the dentist has ultimate responsibility for PM, the dental hygienist also has responsibility to provide comprehensive and individually timed PM for clients who have participated in NSPT. PM continues for the life of the dentition or its implant replacements, and this recommendation must be explained to clients who have NSPT. Clients with gingivitis and periodontitis have a chronic disease entity that must be controlled by frequent periodontal care and daily self-care.

Goals of Periodontal Maintenance

Intervals for Periodontal Maintenance

Clients with gingivitis and without a history of attachment loss maintain their oral health status when PM is performed every 6 months. For clients with periodontitis, a 3-month interval or shorter is ideal. Part of the rationale for 3-month intervals is that after periodontal pathogens are suppressed, they return to pretreatment levels in 9 to 11 weeks; however, this interval varies significantly among clients. Even though 3 months is the ideal interval, the PM interval is customized to the client based on self-care compliance, extent of disease, systemic contributions to disease, risk factors, and client consent. Factors that influence client consent to a specific interval are cost, third-party benefits, cooperation, personal values, and needs.

Components of Care

Components of PM should be similar at each PM visit; however, the extent of these services may vary depending on client compliance, length of time in PM, and extent of periodontitis. Table 28-5 presents a summary of care for a PM visit and associated risk factors.

TABLE 28-5 Periodontal Maintenance Assessment Criteria, Procedures, and Associated Risk Factors

| Criteria | Procedure | Risk Factors to Evaluate |

|---|---|---|

| Health and pharmacologic history | Review and update for: | |

| Dental history | Review and determine chief complaint | Lack of compliance with the continued-care interval |

| Extraoral and intraoral soft-tissue assessment | Examine for significant pathology | Dependent on type of pathology |

| Restorative assessment | Evaluate prosthesis (including implants), caries activity and risk, and restorations | |

| Periodontal assessment | Examine gingiva for color, contour, consistency, texture, position, and mucogingival involvement | |

| Probing depth | ||

| Attachment loss | Extent and severity of disease; type of disease present; 2-mm loss of attachment in 1 year | |

| Radiographs | ||

| Bleeding on probing | Presence indicates risk | |

| Furcation involvement | Presence indicates risk; the more advanced the furcation involvement, the more risk | |

| Mobility | Presence indicates risk; the more advanced the mobility, the more risk | |

| Suppuration | Presence indicates risk | |

| Deposit accumulation | Evaluate location and extent of supragingival oral biofilm | Presence of supragingival oral biofilm is strongly correlated to gingivitis |

| Supragingival and subgingival deposits | ||

| Radiographic assessment | Advancing radiographic bone loss |

Adapted from Hodges KO: Concepts in nonsurgical periodontal therapy, Albany, NY, 1998, Delmar.

Appointment Time

Time required to provide effective PM varies according to the following:

In practice, 60 minutes is probably adequate; however, 45 minutes may suffice in some cases, and others may require 90 minutes. It is challenging in the practice sector to establish a reasonable fee, work with the insurance carriers, and explain needs to the client. A number of insurance carriers will not cover the four annual PM appointments the client needs. In this case the client’s out-of-pocket expense and consequences of inadequate PM are discussed.

Compliance or Adherence12,13

The less threatening the problem appears to be to the individual, the less likely he or she is to comply. Compliance is also reduced if therapy is time consuming and no symptoms are present. Other reasons for noncompliance include self-destructive behavior, fear, economics, health beliefs, stress, and perceived professional indifference. The rate of compliance with toothbrushing is less than 50%; with interdental aids it is even lower. The dropout rate of clients with PM is 11% to 45% in university-based settings; in private practice settings, complete compliance is seen in 33% of cases or less. To improve adherence to professional recommendations, the following are suggested:

PERIODONTAL SURGERY

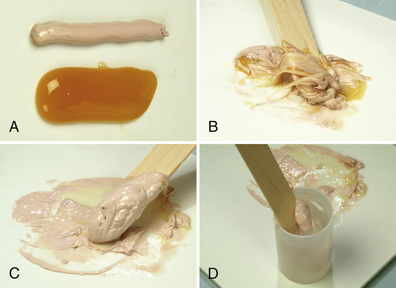

A discussion of periodontal surgical options for clients who need more than NSPT is beyond the scope of this chapter. The reader is referred to any major dental textbook on periodontal therapy. However, after a client has had periodontal surgery, the dental hygienist may be called on to place a periodontal pack. A periodontal pack is a puttylike bandage positioned over the surgical site to protect the area for about 1 week. The pack material (Coe-Pak) is prepared as follows:

Mix thoroughly for about 2 to 3 minutes. Most clinicians use a wooden tongue depressor for mixing because the material is very tacky and difficult to clean up.

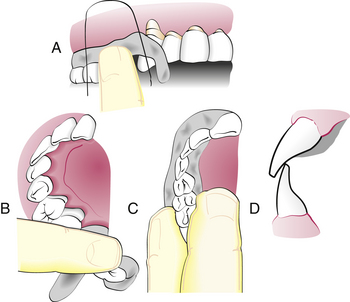

Mix thoroughly for about 2 to 3 minutes. Most clinicians use a wooden tongue depressor for mixing because the material is very tacky and difficult to clean up. When tackiness is gone, roll material into two cylinders for placement on the facial and lingual surfaces of the surgical site. See Figures 28-8 and 28-9 for pack mixing and placement procedures.

When tackiness is gone, roll material into two cylinders for placement on the facial and lingual surfaces of the surgical site. See Figures 28-8 and 28-9 for pack mixing and placement procedures.

Figure 28-8 Preparing the surgical pack (Coe-Pak). A, Equal lengths of the two pastes are placed on a paper pad. B, Pastes are mixed with wooden tongue depressor for 2 to 3 minutes until the paste loses its tackiness (C). D, Paste is placed in a paper cup of water at room temperature. With lubricated fingers, it is then rolled into cylinders and adapted over the surgical wound.

(From Newman MG, Takei HH, Klokkevold PR, Carranza FA, eds: Carranza’s clinical periodontology, ed 10, St Louis, 2006, Saunders.)

Figure 28-9 Inserting the periodontal pack. A, Strip of pack is hooked around the last molar and pressed into place anteriorly. B, Lingual pack is joined to the facial strip at the distal surface of the last molar and fitted into place anteriorly. C, Gentle pressure on the facial and lingual interproximal surfaces joins the pack interproximally. D, Periodontal pack should not interfere with occlusion

(From Newman MG, Takei HH, Klokkevold PR, Carranza FA, eds: Carranza’s clinical periodontology, ed 10, St Louis, 2006, Saunders.)

CLIENT EDUCATION TIPS

Gingivitis is reversible, but periodontitis is not; periodontitis is a chronic, infectious disease. The host’s response to the microbial challenge determines disease progression or control.

Gingivitis is reversible, but periodontitis is not; periodontitis is a chronic, infectious disease. The host’s response to the microbial challenge determines disease progression or control. Evaluation is an integral aspect of nonsurgical periodontal therapy (NSPT), especially in reference to the initial therapy phase of care.

Evaluation is an integral aspect of nonsurgical periodontal therapy (NSPT), especially in reference to the initial therapy phase of care. Prevention and successful treatment of periodontal diseases depend on the co-therapy approach in which the client performs adequate oral self-care and complies with the continued-care interval.

Prevention and successful treatment of periodontal diseases depend on the co-therapy approach in which the client performs adequate oral self-care and complies with the continued-care interval. Oral self-care alone will not maintain or prevent further reoccurrence of periodontitis. Client risk factors must be assessed and modified.

Oral self-care alone will not maintain or prevent further reoccurrence of periodontitis. Client risk factors must be assessed and modified. The care plan for NSPT and periodontal maintenance (PM) is dependent on the client’s genetic, systemic, environmental, and oral conditions and not on the client’s third-party payment plan benefits.

The care plan for NSPT and periodontal maintenance (PM) is dependent on the client’s genetic, systemic, environmental, and oral conditions and not on the client’s third-party payment plan benefits. Risk factors are associated with the development and progression of periodontitis, and they should be eliminated, reduced, or controlled depending on the nature of the risk factor itself (see Chapters 17 and 18).

Risk factors are associated with the development and progression of periodontitis, and they should be eliminated, reduced, or controlled depending on the nature of the risk factor itself (see Chapters 17 and 18).LEGAL, ETHICAL, AND SAFETY ISSUES

The client needs to be informed of the nonsurgical periodontal therapy (NSPT) and periodontal maintenance (PM) care plan and to be involved in the decision-making process. Informed consent and informed refusal should be documented in writing.

The client needs to be informed of the nonsurgical periodontal therapy (NSPT) and periodontal maintenance (PM) care plan and to be involved in the decision-making process. Informed consent and informed refusal should be documented in writing. Referral to a medical professional or other dental professional (periodontist) when indicated is essential. Referral might be because of the clinician’s lack of skill or knowledge to treat, advancing conditions of disease despite therapy, multiple genetic, systemic and/or environmental risk factors, or an aggressive form of periodontal disease. A clinician needs to acquire informed consent if professional consultation related to a medical condition or periodontal disease arises.

Referral to a medical professional or other dental professional (periodontist) when indicated is essential. Referral might be because of the clinician’s lack of skill or knowledge to treat, advancing conditions of disease despite therapy, multiple genetic, systemic and/or environmental risk factors, or an aggressive form of periodontal disease. A clinician needs to acquire informed consent if professional consultation related to a medical condition or periodontal disease arises. Negligence may include the dental hygienist’s failure to protect a client from harm when the client has a systemic disease and failure to record information about the assessment, care plan, informed consent, informed refusal, and interventions related to care. Negligence might occur if NSPT or PM is needed by a client, but the dental hygienist provides oral prophylaxis instead.

Negligence may include the dental hygienist’s failure to protect a client from harm when the client has a systemic disease and failure to record information about the assessment, care plan, informed consent, informed refusal, and interventions related to care. Negligence might occur if NSPT or PM is needed by a client, but the dental hygienist provides oral prophylaxis instead. The hygienist uses evidence-based decision making to select appropriate interventions for care. The dental hygienist must remain current.

The hygienist uses evidence-based decision making to select appropriate interventions for care. The dental hygienist must remain current. Risks associated with care increase with NSPT that involves subgingival periodontal debridement (root planing) and local anesthetic agent use over multiple appointments. Clients need to be informed of the consequences of local anesthetic agent use (i.e., hematoma or paresthesia) and the consequences of periodontal debridement (i.e., bleeding, periodontal abscess, dentinal hypersensitivity).

Risks associated with care increase with NSPT that involves subgingival periodontal debridement (root planing) and local anesthetic agent use over multiple appointments. Clients need to be informed of the consequences of local anesthetic agent use (i.e., hematoma or paresthesia) and the consequences of periodontal debridement (i.e., bleeding, periodontal abscess, dentinal hypersensitivity).KEY CONCEPTS

A disease-free periodontium includes the absence of inflammation and the maintenance of periodontal attachment over time.

A disease-free periodontium includes the absence of inflammation and the maintenance of periodontal attachment over time. Gingivitis is the presence of inflammation without clinical attachment loss and is treated by oral prophylaxis (scaling and selective polishing).

Gingivitis is the presence of inflammation without clinical attachment loss and is treated by oral prophylaxis (scaling and selective polishing). Periodontitis is present when there is loss of clinical attachment and supporting bone. It is treated with nonsurgical periodontal therapy (NSPT) and/or surgery.

Periodontitis is present when there is loss of clinical attachment and supporting bone. It is treated with nonsurgical periodontal therapy (NSPT) and/or surgery. NSPT includes oral biofilm removal and control, supragingival and subgingival scaling, root planing, and the use of chemotherapeutic agents. The host’s response to care must be assessed and risk factors modified.

NSPT includes oral biofilm removal and control, supragingival and subgingival scaling, root planing, and the use of chemotherapeutic agents. The host’s response to care must be assessed and risk factors modified. Periodontal debridement is the removal of subgingival oral biofilm and its byproducts, clinically detectable biofilm retentive factors, and detectable calculus embedded cementum, sufficient to allow healing of adjacent periodontal tissues. The host’s response to care must be assessed and risk factors modified.

Periodontal debridement is the removal of subgingival oral biofilm and its byproducts, clinically detectable biofilm retentive factors, and detectable calculus embedded cementum, sufficient to allow healing of adjacent periodontal tissues. The host’s response to care must be assessed and risk factors modified. Therapeutic endpoint is the restoration of gingival health, a reduction in pocket depth, and a gain in or stable clinical attachment level.

Therapeutic endpoint is the restoration of gingival health, a reduction in pocket depth, and a gain in or stable clinical attachment level. Periodontal assessment is the foundation for providing successful periodontal care including NSPT, periodontal maintenance (PM), and referral to the periodontist.

Periodontal assessment is the foundation for providing successful periodontal care including NSPT, periodontal maintenance (PM), and referral to the periodontist. NSPT is phase I periodontal therapy and is the responsibility of the dental hygienist working in concert with the general dentist or periodontist.

NSPT is phase I periodontal therapy and is the responsibility of the dental hygienist working in concert with the general dentist or periodontist. Chronic disease states of gingivitis and periodontitis progress slowly and can respond to NSPT in a predictable manner; however, aggressive disease states progress rapidly and do not respond in a predictable manner.

Chronic disease states of gingivitis and periodontitis progress slowly and can respond to NSPT in a predictable manner; however, aggressive disease states progress rapidly and do not respond in a predictable manner. Periodontal diagnosis is determined from analyzing information during the assessment phase of therapy and includes health, dental, and pharmacologic history data and disease classification, extent, and severity.

Periodontal diagnosis is determined from analyzing information during the assessment phase of therapy and includes health, dental, and pharmacologic history data and disease classification, extent, and severity. Mechanical pocket therapy is periodontal debridement using manual and/or mechanized instrumentation. Both methods are efficacious.

Mechanical pocket therapy is periodontal debridement using manual and/or mechanized instrumentation. Both methods are efficacious. Evaluation occurs throughout NSPT because gingival inflammation is reassessed 2 weeks after periodontal debridement of an area, reassessment for oral biofilm retentive factors occurs at each subsequent appointment, and reevaluation of the full mouth occurs 4 to 6 weeks after initial therapy.

Evaluation occurs throughout NSPT because gingival inflammation is reassessed 2 weeks after periodontal debridement of an area, reassessment for oral biofilm retentive factors occurs at each subsequent appointment, and reevaluation of the full mouth occurs 4 to 6 weeks after initial therapy. PM follows the active phase of therapy, is appropriately timed based on client need, and continues for the life of the dentition or implant replacements.

PM follows the active phase of therapy, is appropriately timed based on client need, and continues for the life of the dentition or implant replacements.CRITICAL THINKING EXERCISES

Refer to the Procedures Manual where rationales are provided for the steps outlined in the procedure presented in this chapter.

1. Ciancio SG: Non-surgical periodontal treatment. In: Proceedings of the world workshop in clinical periodontics (Section II), Chicago, 1989, American Academy of Periodontology.

2. Bowen D.M. Introduction to nonsurgical periodontal therapy. In: Hodges K.O., editor. Concepts in nonsurgical periodontal therapy. Albany, NY: Delmar, 1998.

3. American Academy of Periodontology. Parameter on chronic periodontitis with slight to moderate loss of periodontal support. J Periodontol. 2000;71:853.

4. American Academy of Periodontology. Parameter on chronic periodontitis with advanced loss of periodontal support. J Periodontol. 2000;71:856.

5. Armitage G.C. Development of a classification for periodontal diseases and conditions. Ann Periodontol. 1999;4:1.

6. American Academy of Periodontology. Parameter on plaque-induced gingivitis. J Periodontol. 2000;71:851.

7. American Academy of Periodontology. Parameter on aggressive periodontitis. J Periodontol. 2000;71:867.

8. Quirynen M., Mongardini C., van Steenberghe D. The effect of a 1-stage full-mouth disinfection on oral malodor and microbial colonization of the tongue in periodontitis patients: a pilot study. J Periodontol. 1998;69:374.

9. Cobb C.M. Nonsurgical pocket therapy: mechanical. Ann Periodontol. 1996;1:443.

10. Cobb C.M. Clinical significance of non-surgical periodontal therapy: an evidence-based perspective of scaling and root planing. J Clin Periodontol. 2002;29:22.

11. American Academy of Periodontology. Position paper: periodontal maintenance. J Periodontol. 2003;74:1395.

12. Wilson T.G. How patient compliance to suggested oral hygiene practices and maintenance affect periodontal therapy. Dent Clin North Am. 1998;42:389.

13. Wilder R. Supportive periodontal therapy: the role of the dental hygienist. Access. 1999;13:26.

Visit the  website at http://evolve.elsevier.com/Darby/Hygiene for competency forms, suggested readings, glossary, and related websites..

website at http://evolve.elsevier.com/Darby/Hygiene for competency forms, suggested readings, glossary, and related websites..