The role of pharmacy in health care

The historical development of pharmacy

The historical development of pharmacy

The position of pharmacy within the National Health Service in the UK

The position of pharmacy within the National Health Service in the UK

Recent developments in the services being provided by pharmacists

Recent developments in the services being provided by pharmacists

Introduction

Pharmacists are experts on the actions and uses of drugs, including their chemistry, their formulation into medicines and the ways in which they are used to manage diseases. The principal aim of the pharmacist is to use this expertise to improve patient care. Pharmacists are in close contact with patients and so have an important role both in assisting patients to make the best use of their prescribed medicines and in advising patients on the appropriate self-management of self-limiting and minor conditions. Increasingly this latter aspect includes OTC prescribing of effective and potent treatments. Pharmacists are also in close working relationships with other members of the healthcare team – doctors, nurses, dentists and others – where they are able to give advice on a wide range of issues surrounding the use of medicines.

Pharmacists are employed in many different areas of practice. These include the traditional ones of hospital and community practice as well as more recently introduced advisory roles at health authority/health board level and working directly with general practitioners as part of the core, practice-based primary healthcare team. Additionally, pharmacists are employed in the pharmaceutical industry and in academia.

Members of the general public are most likely to meet pharmacists in high street pharmacies or on a hospital ward. However, pharmacists also visit residential homes (see Ch. 49), make visits to patients’ own homes and are now involved in running chronic disease clinics in primary and secondary care. In addition, pharmacists will also be contributing to the care of patients through their dealings with other members of the healthcare team in the hospital and community setting.

The changing role of pharmacy

Historically, pharmacists and general practitioners have a common ancestry as apothecaries. Apothecaries both dispensed medicines prescribed by physicians and recommended medicines for those members of the public unable to afford physicians’ fees. As the two professions of pharmacy and general practice emerged this remit split so that pharmacists became primarily responsible for the technical, dispensing aspects of this role. With the advent of the NHS in the UK in 1948, and the philosophy of free medical care at the point of delivery, the advisory function of the pharmacist further decreased. As a result, pharmacists spent more of their time in the dispensing of medicines – and derived an increased proportion of their income from it. At the same time, radical changes in the nature of dispensing itself, as described in the following paragraphs, occurred.

In the early years, many prescriptions were for extemporaneously prepared medicines, either following standard ‘recipes’ from formularies such as the British Pharmacopoeia (BP) or British Pharmaceutical Codex (BPC), or following individual recipes written by the prescriber (see Ch. 30). The situation was similar in hospital pharmacy, where most prescriptions were prepared on an individual basis. There was some small-scale manufacture of a range of commonly used items. In both situations, pharmacists required manipulative and time-consuming skills to produce the medicines. Thus a wide range of preparations was made, including liquids for internal and external use, ointments, creams, poultices, plasters, eye drops and ointments, injections and solid dosage forms such as pills, capsules and moulded tablets (see Chs 32–39).

Scientific advances have greatly increased the effectiveness of drugs but have also rendered them more complex, potentially more toxic and requiring more sophisticated use than their predecessors. The pharmaceutical industry developed in tandem with these drug developments, contributing to further scientific advances and producing manufactured medical products. This had a number of advantages. For one thing, there was an increased reliability in the product, which could be subjected to suitable quality assessment and assurance. This led to improved formulations, modifications to drug availability and increased use of tablets which have a greater convenience for the patient. Some doctors did not agree with the loss of flexibility in prescribing which resulted from having to use predetermined doses and combinations of materials. From the pharmacist’s point of view there was a reduction in the time spent in the routine extemporaneous production of medicines, which many saw as an advantage. Others saw it as a reduction in the mystique associated with the professional role of the pharmacist. There was also an erosion of the technical skill base of the pharmacist. A look through copies of the BPC in the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s will show the reduction in the number and diversity of formulations included in the Formulary section. That section has been omitted from the most recent editions. However, some extemporaneous dispensing is still required and pharmacists remain the only professionals trained in these skills

The changing patterns of work of the pharmacist, in community pharmacy in particular, led to an uncertainty about the future role of the pharmacist and a general consensus that pharmacists were no longer being utilized to their full potential. If the pharmacist was not required to compound medicines or to give general advice on diseases, what was the pharmacist to do?

The extended role

The need to review the future for pharmacy was first formally recognized in 1979 in a report on the NHS which had the remit to consider the best use and management of its financial and manpower resources. This was followed by a succession of key reports and papers, which repeatedly identified the need to exploit the pharmacist’s expertise and knowledge to better effect. Key among these reports was the Nuffield Report of 1986. This report, which included nearly 100 recommendations, led the way to many new initiatives, both by the profession and by the government, and laid the foundation for the recent developments in the practice of pharmacy, which are reflected in this book.

Radical change, as recommended in the Nuffield Report, does not necessarily happen quickly, particularly when regulations and statute are involved. In the 28 years since Nuffield was published, there have been several different agendas which have come together and between them facilitated the paradigm shift for pharmacy envisaged in the Nuffield Report. These agendas will be briefly described below. They have finally resulted in extensive professional change, articulated in the definitive statements about the role of pharmacy in the NHS plans for pharmacy in England (2000), Scotland (2001) and Wales (2002) and the subsequent new contractual frameworks for community pharmacy. In addition, other regulatory changes have occurred as part of government policy to increase convenient public access to a wider range of medicines on the NHS (see Ch. 4). These changes reflect general societal trends to deregulate the professions while having in place a framework to ensure safe practice and a recognition that the public are increasingly well informed through widespread access to the internet.

For pharmacy, therefore, two routes for the supply of prescription only medicines (POM) have opened up. Until recently, POM medicines were only available on the prescription of a doctor or dentist, but as a result of the Crown Review in 1999, two significant changes emerged. First, patient group directions (PGDs) were introduced in 2000. A PGD is a written direction for the supply, or supply and administration, of a POM to persons generally by named groups of professionals. So, for example, under a PGD, community pharmacists could supply a specific POM antibiotic to people with a confirmed diagnostic infection, e.g. azithromycin for Chlamydia.

Second, prescribing rights for pharmacists, alongside nurses and some other healthcare professionals, have been introduced, initially as supplementary prescribers and more recently, as independent prescribers (see Ch. 4).

The profession

The council of the Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain (RPSGB) decided that it was necessary to allow all members to contribute to a radical appraisal of the profession, what it should be doing and how to achieve it. The ‘Pharmacy in a New Age’ consultation was launched in October 1995, with an invitation to all members to contribute their views to the council. These were combined into a subsequent document produced by the council in September 1996 called Pharmacy in a New Age: The New Horizon. This indicated that there was overwhelming agreement from pharmacists that the profession could not stand still. Four main areas in which pharmacy should make a major contribution to health outcomes were identified:

Management of prescribed medicines. This covers drug development, provision of medicines, information and support, and ensuring patient needs are met safely, efficiently and conveniently so that they can get maximum benefit from their medicines.

Management of prescribed medicines. This covers drug development, provision of medicines, information and support, and ensuring patient needs are met safely, efficiently and conveniently so that they can get maximum benefit from their medicines.

Management of chronic conditions. Here the need is to improve the quality of life and outcomes of treatment for the patient. Pharmacists may help by supplying medicines and advice, helping to develop local shared care protocols, ensuring that patients are taking or using their medicines properly and working as part of the healthcare team.

Management of chronic conditions. Here the need is to improve the quality of life and outcomes of treatment for the patient. Pharmacists may help by supplying medicines and advice, helping to develop local shared care protocols, ensuring that patients are taking or using their medicines properly and working as part of the healthcare team.

Management of common ailments. Patients require reassurance and advice, with or without the use of non-prescription medicines and referral to other professionals if necessary (see Ch. 21).

Management of common ailments. Patients require reassurance and advice, with or without the use of non-prescription medicines and referral to other professionals if necessary (see Ch. 21).

Promotion and support of healthy lifestyles. Pharmacists can help people protect their own health through health screening, giving advice on healthy living and providing educational materials (see Ch. 48).

Promotion and support of healthy lifestyles. Pharmacists can help people protect their own health through health screening, giving advice on healthy living and providing educational materials (see Ch. 48).

During the consultation process, pharmacists expressed their views on the way the profession should change. These, too, may be summarized under four main headings:

The strengths of pharmacy. There was a high level of consensus that the knowledge base of pharmacy was very important. This is based on both the study of and experience with medicines and also in managing medicines and handling relevant information. A second strength which was seen as important was pharmacists’ availability and accessibility in a wide range of different locations in the heart of the community, such as conventional high street premises, health centres, supermarkets, hospitals and in people’s homes. This accessibility is strengthened by easy communication with both patients and other professionals, giving pharmacists a pivotal position. The growth of information technology could be a potential threat to this, although pharmacists are noted for their adaptability.

The strengths of pharmacy. There was a high level of consensus that the knowledge base of pharmacy was very important. This is based on both the study of and experience with medicines and also in managing medicines and handling relevant information. A second strength which was seen as important was pharmacists’ availability and accessibility in a wide range of different locations in the heart of the community, such as conventional high street premises, health centres, supermarkets, hospitals and in people’s homes. This accessibility is strengthened by easy communication with both patients and other professionals, giving pharmacists a pivotal position. The growth of information technology could be a potential threat to this, although pharmacists are noted for their adaptability.

Demonstrating the value of pharmacy. Pharmacy must claim its rights as a profession and accept the responsibilities which come with this. Thus high standards must be set and achieved. Additionally, evidence must be produced which demonstrates clearly the value of pharmacy in health care. This will require research and professional audit (see Ch. 12). Further support for this development will come from increased continuing education and recognition achieved by effective promotion of the profession.

Demonstrating the value of pharmacy. Pharmacy must claim its rights as a profession and accept the responsibilities which come with this. Thus high standards must be set and achieved. Additionally, evidence must be produced which demonstrates clearly the value of pharmacy in health care. This will require research and professional audit (see Ch. 12). Further support for this development will come from increased continuing education and recognition achieved by effective promotion of the profession.

Changes in practice. Three main areas where there could be an increase in services were identified. These are: the enhancement of services to patients (advice, counselling, domiciliary visits, health promotion and non-prescription medicine sales); improved relationships with other healthcare professionals (closer support for prescribers, medicine management, liaison between hospital and community pharmacy and different community pharmacists, training for other professionals and carers); and practice research and audit, continuing education and better use of information technology (all required to support the other developments). There was also a high level of support for a reduction in the mechanical aspects of dispensing, sale of non-health-related products and routine paperwork associated with the NHS and business activities.

Changes in practice. Three main areas where there could be an increase in services were identified. These are: the enhancement of services to patients (advice, counselling, domiciliary visits, health promotion and non-prescription medicine sales); improved relationships with other healthcare professionals (closer support for prescribers, medicine management, liaison between hospital and community pharmacy and different community pharmacists, training for other professionals and carers); and practice research and audit, continuing education and better use of information technology (all required to support the other developments). There was also a high level of support for a reduction in the mechanical aspects of dispensing, sale of non-health-related products and routine paperwork associated with the NHS and business activities.

A sustainable future. These elements could make up a sustainable future for the profession. In particular, pharmacy would be concerned with advice and counselling, dispensing, health promotion, the sale of non-prescription medicines, medicines management and as a first port of call for health care. Some of these may require changes in the setting of pharmaceutical provision and others may require different types of employment for pharmacists. Other changes which would be required included changes to the system of payment under the NHS, a rationalization of pharmacy distribution and at least two pharmacists being employed per community pharmacy.

A sustainable future. These elements could make up a sustainable future for the profession. In particular, pharmacy would be concerned with advice and counselling, dispensing, health promotion, the sale of non-prescription medicines, medicines management and as a first port of call for health care. Some of these may require changes in the setting of pharmaceutical provision and others may require different types of employment for pharmacists. Other changes which would be required included changes to the system of payment under the NHS, a rationalization of pharmacy distribution and at least two pharmacists being employed per community pharmacy.

The main output of this professional review was a commitment to take forward a more proactive, patient-centred clinical role for pharmacy using pharmacists’ skills and knowledge to best effect.

The NHS drugs budget

Health services are expensive to run and governments try to reduce expenditure as far as possible. In the UK, some medicines have been identified as being ineligible for prescribing on the NHS. The so-called Black List was introduced in 1984 to reduce the size of the NHS bill. Furthermore the introduction of computer technology into prescription pricing has enabled far more data to be produced than was previously possible. Doctors now receive a regular breakdown of the drugs they have prescribed and that have been dispensed and their prescribing costs, PACT (England) or PRISMS (Scotland)), and this information is also available on line (see Chs 22 and 23).

However, despite these moves, and in common with other developed countries, UK drug costs are inexorably rising due to the greater availability of new effective treatments, patient demand and changes in patient demography (more older people). This has made many governments look at other ways of controlling this item of expenditure, and there are two ways in which pharmacists can have a role.

First, it is recognized that not all prescribing follows the current best evidence for cost-effective practice. Pharmacists are seen as a profession with the necessary knowledge to support quality in prescribing at a strategic and practice level. At a strategic level they can appraise the evidence and make recommendations for the inclusion of a drug in a formulary. At a general practice level pharmacists can advise prescribers on the best drugs to prescribe for individual patients. Community pharmacists are well placed to monitor and review repeat prescriptions, which account for 80% of all prescriptions in primary care.

Second, in a move to promote self-care, pharmacists can encourage patients to be responsible for their own health care and, by implication, remove the cost of treating what is known as ‘minor illness’ from the NHS. Many drugs previously only available on prescription (POM) are now available over the counter from pharmacies (P) or from any retail outlet general sales list (GSL). These changes have resulted in many potent drugs now being available for sale from community pharmacies and the advisory role of the pharmacist has therefore been greatly enhanced (see Ch. 21).

The NHS workforce

As demand for health care grows, it is not only budgets that are stretched. Increasingly, there are insufficient trained professionals to deliver services, and innovative ways of working need to be introduced to maximize the skills of the different professionals in the healthcare team. This has resulted in recognition that many of the tasks previously undertaken by the medical profession, in both primary and secondary care, can be undertaken by other professions such as pharmacists and nurses. Thus, some of the professional roles originally identified by the profession, such as the management of chronic disease and a greater role in responding to symptoms are now supported by the wider healthcare community because they can contribute to more effective health care for the population. As a result, a team approach to managing health care has emerged.

The current and future roles of pharmacists

There are currently around 46 000 UK member pharmacists registered with the General Pharmaceutical Council, including those who are working in different sectors of the profession. Approximately 70% work in community pharmacy, 20% in hospitals, 8% in primary care and 4% in the pharmaceutical industry.

Community pharmacy

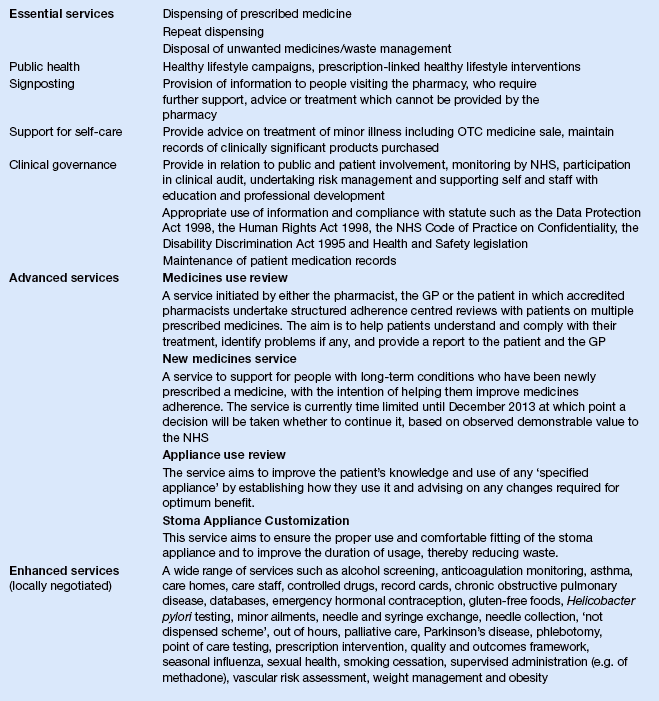

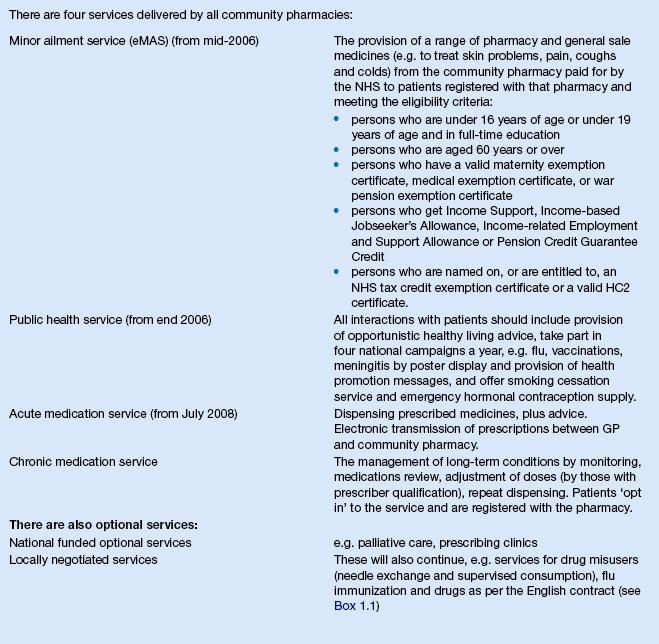

As a result of the final recognition of the pharmacist’s role beyond solely dispensing, new community pharmacy contractual frameworks were agreed for England and Wales, and for Scotland, in the early part of this century. In England and Wales, the contract is based on a list of essential services to be delivered from all NHS contracted pharmacies, and then an advanced service specification for specially accredited pharmacists operating from enhanced premises with private consultation areas. At the time of writing, there are four advanced services: the medicines use review (MUR) and prescription intervention service; the appliance use review (AUR); stoma appliance customization (SAC); and the new medicines service (NMS). Enhanced services, which are negotiated locally with individual NHS primary care organizations, are also delivered. These are summarized in Box 1.1. In Scotland, the new contract is similar, but there is an emphasis on all pharmacists delivering all of the four core service areas: these are the acute medicines service (AMS); the chronic medicines service (CMS); the minor ailment service (MAS); and the public health service (PHS). More detail on these is provided in Box 1.2. In Northern Ireland, a new contract is proposed but is not yet delivered. However, locally agreed contracts are supporting extended roles for community pharmacy, for example in providing smoking cessation services and Minor Ailment Services. In summary, whichever contractual framework pharmacists are operating under, the following generic services will be delivered to some extent.

Dispensing, repeat dispensing and medication review

Despite the recent contractual recognition of new clinical roles, which are described later, dispensing remains a core role of community pharmacy and would still account for the majority of a pharmacist’s time. The preponderance of original pack dispensing means that, compared with even a decade ago, while the name may remain the same, the similarity ends there. The focus of dispensing now rests not only on accurate supply of medication, but also on checking that the medication is appropriate for the patient and counselling the patient on its appropriate use. All community pharmacists maintain computerized patient medication records which are a record of previous prescriptions dispensed. While not necessarily complete, since patients are not registered with an individual pharmacy, in practice, the vast majority of patients, particularly those on regular prescribed medication, do use one pharmacy for the majority of their supplies. Thus, pharmacists have a database of information, which will allow them to check on issues such as accuracy of the new prescription, compliance and potential drug interactions.

In the future, the dispensing role will be further enhanced as connection of community pharmacy into the NHS net becomes a reality. Electronic transmission of prescriptions is being implemented. Under this scheme, GPs send prescriptions to a central ‘cyberstore’ from which pharmacists can download the information using a unique identifier, and dispense the prescribed supplies or medications to the patient. Ultimately, this electronic link should allow access by the pharmacist to at least a selected portion of the patient’s medical records, further enhancing the pharmacist’s ability to assess the appropriateness of the prescription. It is hoped that there will also be a facility for pharmacists to write to the patient record, so that GPs will know whether or not prescriptions have been dispensed and what OTC drugs have been purchased.

A further enhanced dispensing role is in the management of repeat prescriptions, which until recently, have been issued from GP surgeries with little clinical review. Following research projects which demonstrated that when given this responsibility, community pharmacists could identify previously unrecognized side-effects, adverse drug reactions and drug interactions, as well as saving almost one-fifth of the costs of the drugs prescribed, this repeat dispensing service is now part of the new community pharmacy contract (see Boxes 1.1 and 1.2).

This opportunistic clinical input at the point of dispensing is also being developed in a more systematic way, in that patients with targeted chronic conditions, such as coronary heart disease, have formal regular reviews with the community pharmacist about their medication and other disease-related behaviours. Again schemes like this, with research evidence of benefit in small studies, are currently undergoing national implementation through the new contractual frameworks. Such services, called medicines management (see Ch. 20), MUR, NMS or CMS, are part of a more holistic approach often referred to as pharmaceutical care. Supplementary and independent prescribing will greatly enhance this role for pharmacy.

Responding to symptoms

Provision of advice to customers presenting in the pharmacy for advice on self-care is now an accepted part of the work of a pharmacist which, as described earlier, has been enhanced by the increased armamentarium of pharmacy medicines. Advertising campaigns, particularly those by the National Pharmaceutical Association (NPA), have brought to public attention the advice which is available from the pharmacist, as have the commercial adverts from the pharmaceutical industry for their deregulated products. The increased emphasis on the provision of advice from community pharmacies has also extended to the counter staff, who require special training and must adhere to protocols (see Ch. 21).

The full contribution of this advisory role to health care has been limited, to some extent, to the more advantaged sections of the population, particularly since the deregulation of many potent medicines referred to earlier. Many of these newer P medicines are relatively expensive, and those on lower incomes, and particularly those who are exempt from prescription charges, may in the past have attended their doctor only for the purpose of obtaining a free prescription for the drug. This has now been circumvented. Under the contract in Scotland, all patients who meet certain criteria mostly related to age (e.g.<16 years of age or>60 years of age) or income (see Box 1.2) can access any medicine normally available from a pharmacy, without a prescription and on the NHS, from their local community pharmacist. Patients have to register with a community pharmacy to receive the service and all records are maintained centrally and electronically. Ultimately, they will be able to be linked to other patient information through a unique patient identifier, known as the CHI (Community Health Index). In England, similar schemes also exist under the new contract but they are an enhanced, locally negotiated service, rather than an essential service. At the time of writing, only about 12% of English community pharmacies provide this service.

Health promotion and health improvement

A large number of people pass through the nation’s pharmacies in any one day; on the basis of prescription numbers, this is frequently said to be 6 million people per day in the UK. Another way of looking at this is that over 90% of the population visit a community pharmacy in any single year. Thus, the pharmacist is one of the best placed healthcare professionals to provide health promotion information and health education material to the general public (see Chs 13 and 48). This has now become part of the pharmacist’s NHS contract and formalized as a core service to be delivered by all pharmacies in England and Wales, and Scotland. The service specification is generally limited to participation in healthy lifestyle campaigns and opportunistic intervention. More aspirational roles can also be delivered and there are extensive opportunities for proactive, targeted and specialist advice to be provided from community pharmacies. Pharmacists can give out patient information leaflets on healthy nutrition, which may reduce the development of disease which would otherwise occur and lead to the need for expensive treatment. Smoking is considered to be the single biggest cause of preventable ill health. Pharmacists have a successful record in supporting smoking cessation through tailored face-to-face advice and the supply of smoking cessation products such as nicotine replacement therapies (see Ch. 48), and the vast majority of pharmacies are engaged in local smoking cessation schemes. In Scotland, 70% of all quit attempts and 60% of all quits are delivered through community pharmacy. Studies to quantify the contribution community pharmacists can make to weight, exercise and alcohol consumption are ongoing.

Services to specific patient groups

Certain groups of patients have particular needs which can be met by community pharmacists more cost-effectively than by any other healthcare professional. One such example is drug misuse and its link to the spread of blood-borne diseases such as hepatitis and AIDS. Drug misuse is an increasing problem in society today (see Ch. 50). It is now generally accepted that drug misusers have a right to treatment both to help them overcome their addiction and to reduce the harm they may do, either to themselves or to society, until such time as they are ready to undergo detoxification. In particular, pharmacists have become involved in needle exchange schemes and in instalment dispensing and supervised consumption of methadone. Because of the urgent need for these important services, and to some extent because of the unwillingness of some community pharmacists to become involved, these services have unusually been recognized by specific locally negotiated remuneration packages.

Domiciliary visiting

Many pharmacists will visit a small number of patients in their own home to deliver medicines and provide advice on their use. This will now be extended to include other situations where patients could benefit, such as on discharge from hospital, including highly specialized services (often called the ‘hospital at home’) where patients may be on palliative care, cytotoxic agents, intravenous antibiotics or artificial nutrition (see Chs 44 and 46). As medicines’ management services for people on chronic medication continue to evolve, and with more early hospital discharge, this could mean more domiciliary visits to housebound patients. There is also a separate but related need for services to be provided in care home settings, to include both advice on the storage and administration of medicines as well as clinical advice for individual patients (see Ch. 49).

Personal control

One of the requirements of the current regulations is that a pharmacist has to be in personal control/supervision of registered community pharmacy premises at all times. The principle is that the pharmacist should be aware of any transaction in which a medicine is provided to a member of the public and be able to intervene if deemed necessary. This requirement was intended to protect the public but it has been a barrier to innovative practice, and it has been interpreted as the pharmacist needing to be physically present in the pharmacy and aware of all transactions involving P and POM medicines. For single-handed pharmacists this has been difficult to combine with new roles undertaken outwith the pharmacy premises, such as domiciliary visits, or multi-professional meetings. In 2008, the Responsible Pharmacist Regulations were introduced which require that a retail pharmacy business must be in the charge of a named registered pharmacist who is the responsible pharmacist. Under these regulations, the responsible pharmacist can be absent for up to 2 hours per day; different activities can take place in the pharmacy when the pharmacist is present and absent, guided by whether not the physical presence of the pharmacist is required. For example the sale and supply of Pharmacy medicines requires the pharmacist to be present but the sale and supply of General Sales medicines does not. In general, there are moves to promote greater use of professional judgement, and this is reflected in the current Standards of Conduct, Ethics and Performance, which with successive editions, emphasizes principles and removes prescriptive details.

A further challenge to established practice will also come from the increasing use of the internet for personal shopping; and the acquisition of medicines, whether prescribed or purchased, will not be immune to such developments. Already mail order pharmacy and e-pharmacy are making small inroads into medicines distribution and supply, and challenge some of the Standards of conduct, ethics and performance and professional practice points which encourage personal counselling wherever possible. Again, the new Standards document has responded appropriately, with guidance to professionals on how they can still deliver the same standards of care as from face-to-face premises. Although online services are probably more developed in North America, such changes to practice are inevitable and need to be managed professionally, remembering that best care of the patient, rather than professional self-interest, must be the rationale of any decision-making.

Out of hours services

The NHS call centres: NHS 111 (England), NHS Direct (Wales) and NHS 24 (Scotland), handle health-related telephone enquiries from the general public and triage them on to appropriate services. Referral to community pharmacy is one of the formal dispositions included in the algorithms used by the call handlers. It is intended, therefore, that the community pharmacist will not be bypassed by the new telephone help lines. It should also serve to educate the public about the role of the community pharmacist and to increase general awareness that the community pharmacy is just as much a part of the NHS as is the general practice. Audits of calls have revealed that a high proportion are linked to medicines and could have been handled directly by pharmacists. As a result, pharmacists are now employed directly to provide online advice from NHS 111/NHS 24/NHS Direct phone lines, and there is also a recognized need to divert the public back to the community pharmacist as the port of call during normal working hours. Finally, there are moves to extend accessibility to face-to-face out of hours pharmaceutical advice through links between community pharmacies and out of hours centres.

Hospital pharmacy

Clinical pharmacy services have been established in the hospital setting for some time. In general, there is already a greater working together of the professions in the hospital setting compared with primary care, including pharmacists’ involvement in medication history taking, active engagement in research and for the provision of 24-hour services. In 1988, the NHS circular ‘Health Services Management: the Way Forward for Hospital Pharmaceutical Services’ laid down the government policy aim as ‘the achievement of better patient care and financial savings, through the more cost effective use of medicines, and improved use of pharmaceutical expertise obtained through the implementation of a clinical pharmacy service’. Two main components were identified. One is the overall management of medicines on the hospital ward. This is achieved through the provision of advice to medical and nursing staff, formulary management and ensuring the safe handling of medicines. The other component is the development of individual patient care plans. This is achieved through the provision of drug information and assisting patients with problems which may arise. In practice there are many stages and activities involved in these processes. A working group in Scotland published Clinical Pharmacy in the Hospital Pharmaceutical Service: a Framework for Practice in July 1996 (Clinical Resources Audit Group 1996). The framework advocates a systematic approach to enable the pharmacist to focus on the key areas and optimize the pharmaceutical input to patient care. One specific area where pharmacists have been called on to support better prescribing is in the appropriate use of antibiotics. Many hospitals have specialist antibiotic pharmacists whose role is to promote the correct use of antibiotics and hence reduce the spread of antibacterial resistance and associated problems, such as those caused by Clostridium difficile and MRSA.

There is growing awareness of the problems which arise at the interface between community (primary) and hospital (secondary) care. Patients move in both directions. Their medical and pharmaceutical problems also move with them. Over the next few years, it is hoped that a large proportion of these problems will have been resolved through the greater involvement of pharmacists at admission and discharge with effective (ultimately electronic) transfer of information, from hospital pharmacist to community pharmacist. As more patients are discharged early, and with more serious and specialized clinical conditions, there will need to be greater communication at this interface and possibly hospital pharmacists operating outwith their traditional secondary care base.

As in community pharmacy, the need for technical skills for local manufacturing of individual products is also now greatly reduced and the skills of hospital pharmacists are more utilized in decisions about the cost-effective and clinically effective selection of drugs, and contributing to drug and therapeutic committees, formulary groups and quality assurance procedures (see Chs 22 and 23). Issues of supply and efficient distribution of medicines are increasingly becoming automated.

Other NHS roles

Primary care pharmacy

During the 1990s, there was increasing evidence of close working between pharmacists and the rest of the general practice based primary healthcare team. Doctors realized that pharmacists had many possible additional clinical roles in primary care, beyond their traditional community pharmacy premises. Many pharmacists now provide doctors with advice on GP formulary development (see Ch. 23) and undertake patient medication reviews, either seeing patients face-to-face or through review of patient records, either globally or on an individual basis. They may also take responsibility for specific clinics following agreed protocols, such as anticoagulant and Helicobacter pylori assessment clinics. These pharmacists are known as primary care pharmacists. As community pharmacy develops and IT links become the norm, many of the tasks now done by primary care pharmacists will ultimately be carried out from the community pharmacy base.

Pharmaceutical advisers

Pharmaceutical advisers co-ordinate pharmaceutical care for primary care organizations, integrating community pharmacy into the delivery of core health care, and coordinating the primary care pharmacist workforce to achieve area wide goals in prescribing. As new NHS structures emerge involving GP-led commissioning bodies, the pharmaceutical advisor role may change.

Pharmaceutical public health

Strategic health authorities in England and NHS boards in Scotland administer large geographical areas. Many of these also have a senior pharmacist, operating at consultant level, as part of the public health team. They have a specific responsibility for local pharmacy strategy development, compliance with statutes and the managed entry of new drugs, as well as providing local professional leadership and advice on professional governance alongside other senior pharmacy colleagues. Increasingly, as professional boundaries begin to merge, they are also seen as public healthcare professionals and take their share of the generic public health workload.

The public’s view

Increasingly, patient satisfaction with new services is monitored in formal health services research projects, as part of innovative pilot schemes and for ongoing routine quality control. Indeed, one of the requirements of the new contracts is that community pharmacists should ‘have in place a system to enable patients to give feedback or evaluate services’. Large surveys of the public’s opinion of community pharmacy services have also been conducted. In general, such surveys find that the public are satisfied with the service they receive, and that pharmacy is a trusted profession. Research also tells us the public regard community pharmacy services as an important resource for them to access when managing symptoms of minor illness, and that they prefer to seek such advice from a pharmacist rather than a GP or one of the NHS online services. However, it is also shown that they are more wary of hypothetical situations in which pharmacists become involved in the delivery of new roles which have previously been delivered by GPs or nurses working with GPs. In particular, older people are less open to new models of service, whereas younger people are much more positive. Once new services have been trialled, such as repeat dispensing, medicines management and prescribing, patient feedback is highly positive. Nonetheless, when asked whether or not they would prefer a doctor or pharmacist to provide the service, there is a status quo bias in favour of the GP. This is not really surprising, but the profession needs to be aware of this. New services have to earn their place in the public’s esteem, building confidence in the quality of what they offer and the advantages of pharmacy delivered services. There is also a need for other healthcare professionals to value the pharmacist’s new roles and to recognize their increasingly central place in the NHS team.

Clinical effectiveness

Clinical effectiveness is a term often used to describe the extent to which clinical practice meets the highest known standards of care. Clinical governance is a term used to describe the accountability of an organizational grouping for ensuring that clinical effectiveness is practised by all functions for which it is responsible (see Ch. 9). Central to this is the use of evidence-based guidelines and protocols, which have increased dramatically in the past decade. These guidelines are a way of increasing the quality of service because they are developed after systematic searches of the research evidence and make recommendations for ‘best practice’, which are easily understood and widely accepted.

The extent to which guidelines are actually applied in particular situations should be measured by clinical audit (see Ch. 12). Audit is also an important tool in the raising of standards of service delivery.

The roles of the Royal Pharmaceutical Society and the General Pharmaceutical Council

The RPSGB historically undertook an unusual dual role as a professional body and a regulatory body, being responsible for both developing and promoting the profession and the registration of pharmacists and premises, the maintenance of standards though a network of inspectors, and for disciplining those who do not meet the required standard. With increasing public concerns about standards of health care in general, the UK Council for the Regulation of Healthcare Professionals was established. As part of its review of the regulation of all healthcare professionals, a recommendation was made that the regulatory functions of the RPSGB would be delivered by an independent body, the General Pharmaceutical Council, and a new body for pharmacy was created to deliver the complementary professional role: the Royal Pharmaceutical Society. While membership of the GPhC is mandatory for all those wishing to practice as pharmacists, membership of the RPS is voluntary, although strongly to be encouraged.

Continuing education and continuing professional development

In such a rapidly changing profession, there is a need for continual updating of knowledge. The RPS through The Pharmaceutical Journal, has established a regular pattern of continuing education (CE) articles on a wide range of topics and introduced a formal web-based continuing professional development (CPD) initiative. The GPhC, through the standards of conduct, ethics and performance, requires that all pharmacists keep a record of their CPD and the GPhC can request this record be submitted to them for review at any time. There is a standard of a minimum of nine entries per year to reflect the context and scope of practice and describe how the CPD has contributed to the quality and development of the individual’s practice. This approach is thus more about tailored personal and professional development (see Ch. 6).

Pharmacy education

Undergraduate education

Teaching of pharmacy was traditionally under four subject headings: pharmaceutical chemistry, pharmaceutics, pharmacology and pharmacognosy. This was seen as a restraint on the development of new ideas of teaching to make the course more relevant to the profession. The course has to have a firm science base, building on knowledge acquired in secondary school, but be relevant to practice. Pathology and therapeutics, law and ethics and the teaching of dispensing practice all have their place alongside clinical pharmacy, which is now accepted as a subject in its own right and one of the most important parts of the course. The course also includes social and behavioural science – a broad subject area which covers many sociological and psychological aspects of disease and patients – and communication skills. Although communication cannot be learned solely by studying a book, it is still useful to have an understanding of the underpinning theoretical framework when learning to put good professional communication into practice (see Chs 3, 4, 17, 25).

Most schools of pharmacy involve both primary and secondary care pharmacy practitioners in undergraduate teaching. The aim of utilizing these teacher–practitioners is to ensure that the university course is relevant to current professional practice. This reflects the situation in other healthcare professions such as medicine. Other ways of learning from current practice as part of course provision are also used, such as visiting lecturers, making GP practice and hospital visits, using part-time teaching staff, staff secondment to practice and joint academic/practice research studies.

Pre-registration training

The purpose of the pre-registration year is for the recent graduate to make the transition from student to a person who can practise effectively and independently as a member of the pharmacy profession. At the end of the year, the pre-registration trainee has to pass a formal registration assessment prior to entry to the register. Pre-registration training is carried out, in either hospital or community pharmacy practice, in a structured way with a competency-based assessment after 12 months. Some of the differences between community and hospital practice are becoming less distinct as pharmacists in the community take on roles which in the past have been common in hospital practice, such as prescribing advice to doctors. In the future, it may be that a combined pre-registration year may be introduced and interchange between the two areas of practice will become easier to achieve than it is at present (see Ch. 5).

Higher degrees and research

A wide range of taught MSc and Diploma courses are offered in the UK. Subject matter may be very specialized or more general. Study may be full-time or part-time. There are also distance learning courses for those who have limited opportunity to be away from their place of work. Additionally, taught PharmD courses are gaining in popularity and are provided in a small number of institutions across the UK. The programmes are intended to allow pharmacists to develop specialist skills in their chosen area, through formal learning, together with the conduct of either a substantive piece of research or work-based project.

Research has also developed, and research articles appear regularly in the Pharmaceutical Journal and the International Journal of Pharmacy Practice, as well as other academic journals from medicine and primary care. There are practice research sessions at the British Pharmaceutical Conference each year, and there is an annual dedicated Health Service and Pharmacy Practice Research Conference. Many students are now graduating with a doctorate for studies undertaken in aspects of pharmacy practice, and, reflecting the integrated multidisciplinary delivery of care, many pharmacists are carrying out research in multidisciplinary research teams. The development of the discipline of pharmacy practice research is something of which the profession should be justifiably proud. The generation of research evidence of the clinical and cost-effective contribution which pharmacists can make to health care has had a key part to play in the innovations in professional practice we have seen in the past decade, and which have been summarized in this introductory chapter.

Conclusion

During the twentieth century, pharmacy underwent major changes. This process has accelerated since the introduction of the NHS in 1948, the Nuffield Report in 1986 and, most recently, the new plans for the NHS published at the turn of the century. As will be evident from reading this chapter, many changes are still ongoing, demonstrating the vibrant and dynamic nature of both the health service and of our profession. Pharmacists now deal with more potent and sophisticated medicines, requiring a different type of knowledge and a different skill set than was previously the case. At the same time, the public has become more aware of the services that are available from pharmacists. People are making increasing use of the pharmacist as a source of information and advice about minor conditions and non-prescription medicines. This is now extending to the general public regarding pharmacists as a source of information and advice about their prescribed medicines and seeking help from pharmacists with any medication problems they may encounter. This process is likely to develop further through the twenty-first century. We are also likely to see further changes reflecting the merging of professional boundaries and competency-based delivery of health care. Thus, generic healthcare professionals may emerge, and many may undertake tasks traditionally undertaken by one profession. In addition, in order to free up professional time, we can expect to see pharmacy technicians taking on greater responsibility for the technical aspects of the pharmacist’s role, while qualified pharmacists concentrate on cognitive functions and interact directly with the patient.

Pharmacists need to have the knowledge and adaptability to take a lead in these processes, so that they can have a key role in ensuring that the health care of the public can be delivered as efficiently as possible. The undergraduate pharmacy courses must reflect these changes to ensure that their graduates meet the demands of the future NHS workforce.

Key Points

The UK NHS came into being in 1948

The UK NHS came into being in 1948

Early developments in the NHS were in hospital services, but this has gradually changed to focus on community practice

Early developments in the NHS were in hospital services, but this has gradually changed to focus on community practice

Publication of the Nuffield Report in 1986 marked a watershed for pharmacy in the UK

Publication of the Nuffield Report in 1986 marked a watershed for pharmacy in the UK

New community pharmacy contracts in the UK are delivering the vision together with regulatory changes such as patient group directions and supplementary and independent prescribing

New community pharmacy contracts in the UK are delivering the vision together with regulatory changes such as patient group directions and supplementary and independent prescribing

Education at undergraduate and postgraduate levels reflects these changes and pharmacy graduates are well trained for their new roles

Education at undergraduate and postgraduate levels reflects these changes and pharmacy graduates are well trained for their new roles

The public values the pharmacist but still has some reservations about too much care being delegated from doctors

The public values the pharmacist but still has some reservations about too much care being delegated from doctors