Chapter 18 Mobility and immobility

Introduction

This chapter focuses on human movement and its importance to health. The introductory section provides an overview of the nervous and musculoskeletal systems and their role in movement. The musculoskeletal system comprises the bones, joints and skeletal muscles, each of which is briefly described. First aid for conditions affecting components of the musculoskeletal system is outlined and the principles of nursing care for people with casts, traction and external fixators are explained. The second section explores factors that influence balance, posture and movement. Development of the spinal curves and the importance of maintaining them are described. The next section extends the principles of safe handling and moving that were introduced in Chapter 13 to moving patients/clients, including the use of equipment such as hoists, glide sheets and transfer boards. Helping people to mobilize, including the use of walking aids and wheelchairs, is outlined. In the following section the benefits of mobility and the hazards of immobility are introduced and the problems that people of all ages may experience due to immobility are explained. Active and passive exercises are described. This chapter refers to others that provide more detail about potential hazards of immobility such as pressure ulcers (Ch. 25), deep vein throm-bosis (Ch. 24) and constipation (Ch. 21). The principles of bedmaking are outlined. A multidisciplinary approach is normally taken to provide care for people with mobility problems and usually involves at least a physiotherapist and occupational therapist (OT) as well as the nursing team, and their role in promoting mobility is described in the final section.

The nervous and musculoskeletal systems

This section outlines the anatomy and physiology of the musculoskeletal and nervous systems and their roles in mobility. You should refer to your physiology text for more detail of the related anatomy and physiology and to Chapter 16 for a fuller explanation of disorders affecting the nervous system. First aid for fractures, dislocations, sprains and strains is described and the principles of nursing care for people with casts, traction and external fixators are explained. An overview of common disorders of muscles, bones and joints is included.

Nervous system

The nervous system consists of the brain, spinal cord and peripheral nerves that allow rapid communication throughout the body (see Fig. 16.2). Three types of nerve are responsible for conducting impulses:

Stimulation of motor nerves brings about contraction, or shortening, of the muscle supplied. When motor nerve stimulation stops, the muscle returns to its resting length. Since many motor nerves supply a single muscle, the spinal cord and brain can regulate the strength of a muscle contraction. When only a few muscle fibres (cells) are stimulated, the movement is not very forceful. However, if all the muscle fibres are stimulated at the same time, the contraction is much stronger. For example, moving one’s hand gently stimulates fewer muscle fibres than when throwing a stick. Additionally, as different nerves transmit signals to muscle fibres at different speeds, some muscle actions are faster than others.

The musculoskeletal system

The structure and functions of the components of the musculoskeletal system are outlined, together with some common conditions that may affect them. Many of these disorders impair mobility.

Voluntary muscles

Voluntary (skeletal) muscles are those in the body that are attached to two bones with a movable joint between them. One of the bones is usually more stationary at a given moment than the other to allow movement to take place between them. Skeletal muscle has a striped appearance under microscopic examination and muscle tissue has four characteristics:

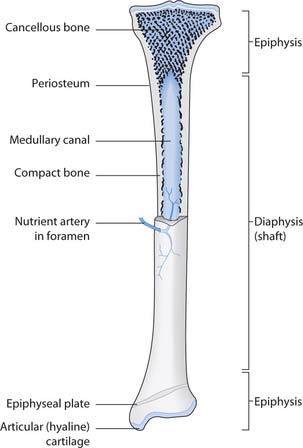

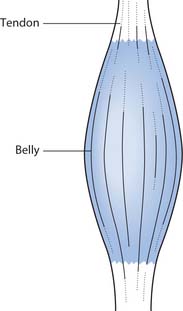

Muscles come in different shapes and sizes depending on their function, and they usually have a thicker belly and a tendon at each end for attachment to bone (Fig. 18.1). The muscles around the mouth are circular, allowing the mouth to open and close fully during eating, whereas the muscles of the forearm are long and thin, allowing the wrist and fingers to flex while making a fist, and to extend during movements such as waving.

Postural muscles help to keep the upright posture or maintain positions for sustained periods of time and do not tire quickly. Examples include the muscles of the abdominal wall, buttocks and thighs. Active muscles are involved in movements such as typing, running and blinking. They allow muscles to respond appropriately to the tasks they perform but tend to tire quickly (Box 18.1). Muscle disorders are outlined in gTable 18.1 and first aid interventions for strains and sprains, and their subsequent neurovascular checks, in Boxes 18.2 and 18.3, respectively.

Understanding the musculoskeletal system

Student activities

Strains and sprains

Treatment (acronym RICE)

Table 18.1 Disorders of the musculoskeletal system

| Disorder | Causes and effects |

|---|---|

| Muscles | |

| Cerebral palsy | This condition is primarily neurological but is characterized by neuromuscular abnormalities |

| It can be caused by brain damage due to hypoxia either before or during birth and results in impaired coordination and muscle control | |

| Intellect can be unaffected but because clients cannot articulate words easily care must be taken not to assume this is the case although learning disability is sometimes present | |

| Muscular dystrophies | This is a general term used to describe genetically inherited conditions that lead to skeletal muscle wasting without any nerve damage |

| Congenital muscular dystrophy can be present at birth or manifest within the first 6 months of life | |

| Signs include generalized muscle weakness and poor head control | |

| Duchenne muscular dystrophy is a rapidly progressive condition that only affects boys and is often fatal during adolescence; it is present from birth but may not become evident until around 4 years of age | |

| Not all muscular dystrophies are congenital (present from birth) | |

| Strains | Strains occur during overexertion of all or part of a muscle, e.g. the calf muscles during jogging and other keep-fit exercises |

| If a muscle is not warmed up adequately and too much work is demanded of the fibres, it becomes exhausted, and tightens and shortens | |

| The signs of muscle strains and the interventions required are shown in Box 18.2 | |

| Bones | |

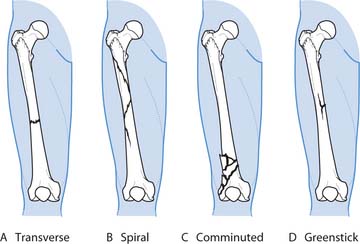

| Fractures | A fracture is a break in the continuity of a bone, usually caused by excessive force being applied to it |

| In simple fractures the skin remains intact; however, in compound fractures the broken bone protrudes through the skin | |

| Figure 18.4 shows different types of fracture: Spiral fractures are common in footballers and skiers because they tend to have the foot fixed in one position, and if the leg and body rotates sharply around it, this causes the bone to fracture (Fig. 18.4B). | |

| In comminuted fractures (Fig. 18.4C) there are many bone fragments due to severe damage at the fracture site | |

| Fractures are diagnosed by X-ray investigation: it can be difficult to diagnose fractures in children because their bones are softer and are more likely to bend than to break. Fractures of this type are called greenstick fractures (Fig. 18.4D) because the characteristics are similar to bending a green twig. The outer layers of the twig split, while the soft wood underneath only bends | |

| Some fractures occur around the epiphyseal plate (see Fig. 18.2). When there is still active bone growth, it is important that these fractures are carefully managed to ensure even growth of bone. Uneven bone growth along the epiphyseal plate will lead to problems with joint alignment, which in turn may cause mobility problems | |

| Box 18.5 shows the signs of fractures and the first aid treatment required | |

| Osteoporosis | This condition is characterized by bone fragility, porosity and an increased risk of fractures, especially of the wrist, vertebrae and hip, particularly in women |

| In the UK, one in two women and one in five men over the age of 50 will suffer a fracture due to osteoporosis (National | |

| Osteoporosis website, see p. 528) | |

| Box 18.4 outlines some of the measures that can be taken to maintain bone density, which will reduce the effects of osteoporosis | |

| Rickets and osteomalacia | These conditions are often referred to as ‘sick bones’ and result |

| Both terms refer to the same condition, known as rickets in children and osteomalacia in adults | |

| In the UK, people most at risk of vitamin D deficiency are those who get little exposure to sunlight; vulnerable groups include people who cover their limbs for cultural/religious reasons, e.g. Moslems, especially women and children, and older adults who are housebound or resident in nursing homes | |

| Lack of vitamin D can lead to generalized bone pain and muscle weakness | |

| In children there may be enlarged bone ends, particularly in the wrists, that cause lasting deformity. | |

| Joints | |

| Arthritis | Inflammation of joints associated with pain, swelling and restricted movement |

| Osteoarthritis: a degenerative disorder usually of weight-bearing synovial joints that commonly accompanies the ageing process, usually due to ‘wear and tear’ or less often following a previous injury | |

| Rheumatoid arthritis: this condition also affects most body systems. Initially the affected synovial joints are often the fingers and wrists; later the larger joints, e.g. the hip, also become affected | |

| Dislocations | Dislocations occur when bones are displaced and the joint can no longer function |

| They may be caused when excessive force is placed on a bone, pulling it out of alignment, or excessive pulling on a joint that causes the ligaments to tear | |

| A partial dislocation (subluxation) requires the same treatment as a full dislocation (see Box 18.5) | |

| Sprains | Sprains arise when damage to the ligaments that surround a joint occurs (see Fig. 18.7) |

| Damaged ligaments weaken a joint and may leave it prone to further injury or dislocation | |

| Damage around the joint may also cause bleeding within it | |

| A common cause of sprains to the neck is a whiplash injury commonly sustained in car accidents. This results from a sudden jerking back of the head and neck causing damage to the ligaments, vertebrae and nerves in the neck region | |

| Signs of sprains and first aid treatment are shown in Box 18.2 | |

| Movement and gait | |

| Parkinson’s disease | This condition is named after Dr James Parkinson (1755–1824) who first identified this progressive neurological disorder, which affects movements such as walking, talking and writing |

| It is typified by tremor, muscle rigidity or stiffness and bradykinesia that typically cause hesitancy in walking, characterized by a shuffling gait and the absence of arm swinging, accelerated walking which can result in falls and difficulty in carrying out fine movements such as buttoning a shirt | |

| Parkinsonism | This describes the symptoms of Parkinson’s disease that occur, e. chlorpromazine for severe mental distress |

Fascia

Fascia is formed from connective tissue, one of the four basic tissues in the body (the others being muscular, nervous and epithelial). Superficial fascia refers to the fatty tissue under the skin and deep fascia refers to the tissue that surrounds muscles, tendons and other organs. The superficial and deep fascias are connected to each other, and the deep fascia that surrounds muscle bellies and tendons is continuous throughout the body. It is incredible to think that the connective tissue surrounding the brain (the meninges) is connected to the fascia in the feet! This is the reason why people with painful knees can be diagnosed with back problems. If the fascia has been damaged in one area, the effects can often be found elsewhere in the body.

Your jumper (see Box 18.1) is a good analogy for the reactions that occur in the fascia when it is shortened or ‘knotted’ through injury. Have you ever felt knots in your shoulder muscles? Did this affect the arm on that side? The effects of postural change may be distant from the original injury. Understanding that fascia is continuous throughout the body helps to understand some of the problems faced by patients/clients who are immobile or trying to regain mobility following illness or injury. The postural characteristics identified earlier have arisen because the muscles and their surrounding fascia have adapted to your habits and protect the shoulder joint from further injury.

These changes are seldom seen in children because their muscles are more elastic and the fascia returns to a near normal position. They also recover more easily from injuries and awkward movements without obvious lasting effect. Fascia stiffens with age. The longer standing a postural habit, the more the fascia adapts to the preferred, habitual position. Understanding that everyone has habits that affect the underlying muscles and tissues also helps to appreciate mobility difficulties that people may have. This knowledge not only helps nurses to move patients/clients more appropriately but also helps them to understand why someone may complain of hip pain when the problem may originate in their shoulder.

Bones

Bones are dynamic, living structures with nerve and blood supplies. The main functions of bones are to:

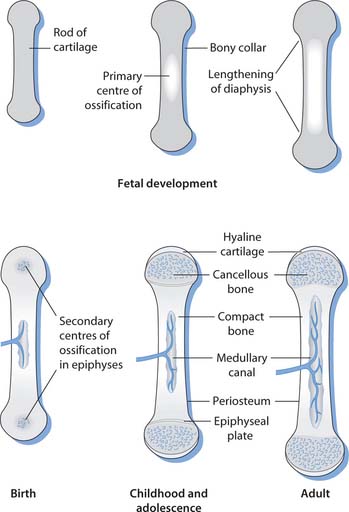

A typical long bone, such as those of the limbs, has a shaft and two epiphyses (Fig. 18.2). Bone growth takes place at each end of the shaft at the epiphyseal plate. This region consists of cartilage until bone growth is complete when it ossifies. Muscle tendons attach to the outer covering of bone, the periosteum. Hyaline cartilage replaces periosteum at the ends of long bones that form synovial joints.

Before birth the long bones consist mainly of cartilage (Fig. 18.3), which is a tough connective tissue. During pregnancy and early childhood, cartilage is gradually replaced by bone tissue. This process is called ossification and takes place at centres of ossification, initially in the bone shaft and at the epiphyses after birth. Until growth is complete, bones increase in both length and diameter, and a rich blood supply provides the nutrients and energy for the necessary cell division to take place. Several hormones, including growth hormone and thyroid hormones (thyroxine, tri-iodothyronine), are important in growth and development of bones, especially in infancy and childhood, and excessive or impaired secretion results in abnormal bone development. In time, ossification is sufficient to allow walking to be achieved. Although cartilage offers some protection to the vital organs, it behaves like stiff plastic, having a degree of flexibility, as it does not have the rigid hardness of bone. As a result, children’s vital organs are more prone to injury if they fall or are shaken than those of adults and their bones tend to bend, rather than break, causing greenstick fractures (see Fig. 18.4).

At puberty, there is often a sudden increase in bone growth due to the increase in production of the sex hormones testosterone and oestrogen. By the late teenage years, ossification is largely complete. Bones are not fully hardened until their growth stops at about 18 years in females and 25 years in males. Bone mass reaches its peak around 30 years of age. It is important to maintain a lifestyle that maximizes bone density in order to reduce the effects of reduction in later life (Box 18.4). The hardness of adult bone protects vital organs such as the brain, spinal cord, heart and lungs from injury.

Promoting bone health

The National Osteoporosis Society

Student activities

Visit the National Osteoporosis Society website (www.nos.org.uk Available July 2006) and find out:

Once bone growth is complete, bones continue to replace old bone tissue with new, a process known as remodelling. For example, the lower third of the femur (thigh bone) replaces itself every 4 months in young adults. Following a fracture, new bone tissue is laid down to repair the break. Box 18.5 describes the treatment required for fractures. Bone mass begins to decrease after about 35–40 years of age. In some people the loss of bone mass is excessive and leads to a condition called osteoporosis. Bone disorders are outlined in Table 18.1.

Fractures and dislocations

Care of people wearing casts, external fixators or traction

This section introduces the roles of casts, external fixators and traction in immobilizing joints and fractured bones and the principles of nursing care are outlined.

People should be as fully participant in their care as possible, particularly as they will need support and encouragement to adapt to their altered body image, whether it is temporary or permanent and regardless of age. This can be particularly challenging during puberty, which brings about many body changes that can be difficult enough for adolescents to deal with, without the added complication of being ‘different’ from their peers because they have to wear a bulky plaster or stay in bed in traction.

Care of people wearing casts

Care of pin sites

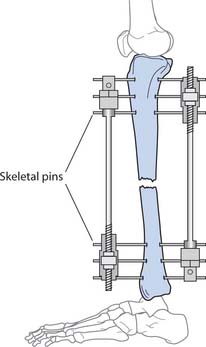

External fixators and skeletal traction involve the use of stainless steel pins and the insertion sites require specific care because infection of the bone (osteomyelitis) into which they are inserted is a serious complication.

Student activity

Using the resources below, find out more about the care of pin sites.

[Resources: Smith M 2003 Nursing patients with musculoskeletal disorders. In: Brooker C, Nicol M (eds) Nursing adults: the practice of caring. Mosby, Edinburgh, Chapter 27; Temple J, Santy J 2004 Pin site care for preventing infections associated with external bone fixators and pins. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 1:CD004551]

Neurovascular checks

These are also sometimes referred to as circulation, sensation and movement (CSM) checks, which are carried out to confirm that a cast, bandage or other intervention does not restrict the local circulation. They are carried out as a first aid measure, following discharge with a new cast and in hospital settings.

The frequency is determined by the type of intervention, the extent of damage, any local policy and reduced over time if observations are within expected levels for the particular patient. Any abnormalities (trends or sudden changes) are reported immediately to the charge nurse. The area, often an extremity, distal to the cast is checked for:

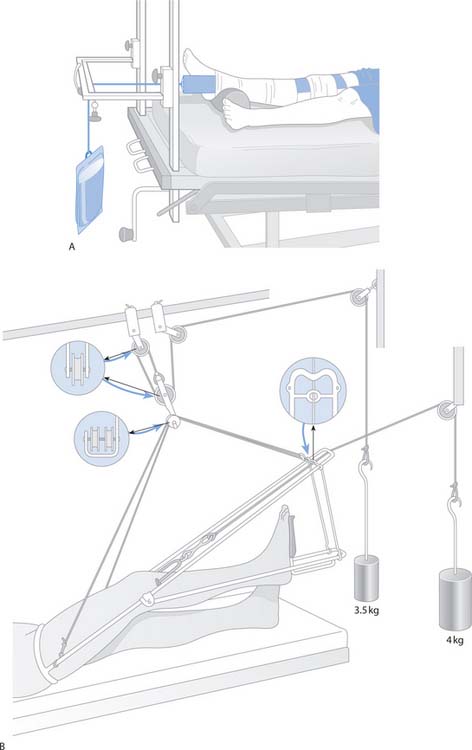

Fig. 18.6 Types of traction: A. Straight leg skin traction. B. Skeletal traction

(reproduced with permission from Brooker & Nicol 2003)

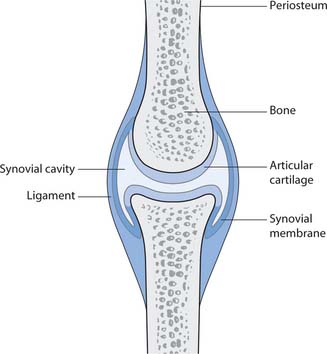

Joints

Joints, or articulations, occur between bones. They hold the bones securely together but may also allow movement. Some joints hold bones together very tightly and do not permit movement, e.g. the sutures of the skull, whereas others, e.g. the hip and shoulder joints, allow a range of movement. This chapter focuses on synovial joints because they are most involved in body movement. It is these movable (synovial) joints that cause most discomfort and pain, and that most often affect mobility if they become diseased or out of alignment.

Figure 18.7 shows a typical synovial joint. The bone ends are covered in hyaline cartilage, which is smooth and shiny. It aids movement between the bones. The joint cavity is lined with synovial membrane and inside is a small amount of synovial fluid, which lubricates the joint. Ligaments consist of white, fibrous tissue and hold the bones together. They are not very elastic and so restrict the amount of movement available and stabilize the joint. Joints are further supported and protected by surrounding muscles, which prevent dislocation (see p. 504) and help to maintain upright posture. Ligaments attach to the periosteum of bones and cross the joint cavity. Twisting a joint, e.g. the ankle, may stretch and tear the ligaments and is known as a sprain.

Muscles work together in antagonistic pairs to allow movements to take place at a joint. Contraction of one of a pair of antagonistic muscles brings about one specific movement and the opposite movement is caused by contraction of the opposing muscle, e.g. the biceps and triceps in the upper arm.

Box 18.8 lists the types of movement available at some joints and Figure 18.8. illustrates some of them. Knowing these movements is important for carrying out passive exercises (movements of joints initiated by an external force, e.g. physiotherapist or nurse, to exercise muscles and joints, see p. 525) or encouraging patients/clients to practise active exercises (movements initiated by an individual that exercise muscles and joints, see p. 525). When caring for people with mobility problems it is important to know the range of movements available at different joints so that they are not moved into positions that could be harmful. This is particularly important when caring for unconscious patients, or following joint replacement surgery. Common joint disorders are outlined in Table 18.1.

Box 18.8 Movements possible at synovial joints

| Movement | Definition |

|---|---|

| Flexion | Bending, usually forward but occasionally backward, e.g. the knee joint |

| Extension | Straightening or bending backward |

| Abduction | Movement away from the midline of the body |

| Adduction | Movement towards the midline of the body |

| Circumduction | Movement of a limb or digit so it describes the shape of a cone |

| Rotation | Movement round the long axis of a bone |

| Pronation | Turning the palm of the hand down |

| Supination | Turning the palm of the hand up |

| Inversion | Turning the sole of the foot inwards |

| Eversion | Turning the sole of the foot outwards |

From Waugh & Grant (2006).

Fig. 18.8 Main movements possible at synovial joints

(reproduced with permission from Waugh & Grant 2006)

Posture, balance and movement

For purposeful movement the body must move in a synchronized manner, with the nervous and musculoskeletal systems working together to ensure that movements are smooth and coordinated, and of the appropriate force for the intended task. To understand why problems with movement occur, it is necessary to know how normal upright posture develops and the principles of human movement and balance. This section explores these areas.

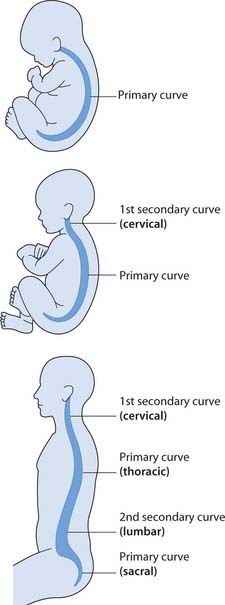

Development of the spinal curves

Babies are born with one ‘C’ shaped spinal curve, which is convex posteriorly. They are unable to control movement of the head, arms or legs and depend on natural reflexes to bring about movement, e.g. the rooting reflex where, in response to lightly touching the side of the cheek, a baby turns its head to that side and begins to suck until the reflex disappears, usually at about 3–4 months of age. The head and spine must be well supported when young babies are moved. At about 6 weeks, babies’ eyes begin to follow colours and movements. This is accompanied by reflex movements in the back of the neck that strengthen the muscles there. Gradually, the neck muscles become bulkier and stronger, and begin to pull the cervical vertebrae and associated muscles into a secondary concave curve, the cervical curve (Fig. 18.9). This enables the head to move from side to side. As babies learn to turn their heads, the muscles around the neck strengthen further and they begin to hold their heads steady on their shoulders for short periods. This is the first stage in developing head control. Gradually thereafter the shoulder muscles strengthen, enabling the muscles of the upper arm to become stronger, leading to more purposeful movements of the upper limbs.

At about 3–6 months the baby learns to sit up, but the back is still very rounded. At this age the baby begins to roll from side to side (Box 18.9). This rotational movement around the spine develops the muscles of the lower back, leading to the development of the secondary concave lumbar spine (see Fig. 18.9), which in turn allows the pelvic girdle to be suspended in its correct position at the bottom of the spine.

Preventing childhood accidents

From the time that babies can roll over, at 3–6 months of age, they are at risk of rolling off a surface if left unattended. A child’s environment needs to be organized to minimize the risk of accidents.

Only when the spine has achieved the lumbar curve can the child begin to walk and graduate to the toddler stage. Eventually the muscles of the upper and lower legs and feet begin to strengthen and the child develops the upright posture. The spinal curves bring the centre of gravity into a straight line (see Fig. 18.9), which allows the body weight to be evenly distributed and helps to maintain balance in all movements.

The thoracic and sacral curves are known as primary curves because they retain the initial convex ‘C’ shape. The cervical and lumbar curves are known as secondary curves because they develop a concave curvature. A child with severe cerebral palsy, who has poor head control, cannot learn how to make meaningful movements with the rest of their body.

Maintaining the spinal curves

Good posture means that the four spinal curves (cervical, thoracic, lumbar and sacral) are in alignment, with the legs suspended from the pelvis. Strong abdominal and back muscles will help to support the spine in a good position. Weak abdominal muscles allow the pelvis to tilt forwards and the lumbar curve to become exaggerated. Habits that encourage the spine to move out of alignment will affect posture because, over time, the fascia adapts to the repeated, sustained tension in the underlying muscles, leading to discomfort and pain. Therefore, people who usually stand bearing most of their weight through one leg and foot, rather than spreading it equally between both legs and feet, will find their spine moves out of alignment affecting their posture.

Tall children tend to droop their shoulders and keep their heads down, to avoid standing ‘head and shoulders’ above their classmates. Carrying heavy school bags on one shoulder can also lead to adaptive shortening of fascia and muscle tissue around that shoulder. The incidence of low back, neck and shoulder problems arising in schoolchildren has increased so much that some European countries demand that children are issued with bags that have straps for both shoulders and that they are fitted with wheels so that the bag can be pulled rather than carried if it is heavy. Lockers should also be provided in schools so that pupils only have to carry the books required for one class at any time.

Peer pressure (see Ch. 8) and the need to conform to fit in with a group can have lasting effects on people’s posture and mobility. Teenagers tend to slouch, when both standing and sitting, and girls may also slouch because they are embarrassed by development of breasts and comments made by others. It can therefore be difficult to maintain a good posture if it makes an individual stand out from the crowd. However, posture is more than just the ability to stand or sit in a good upright position: it is a balanced action of muscles to maintain all parts of the body in positions that do not involve undue strain, and from which immediate coordinated action of any part of the body is possible.

Normally, babies and toddlers do not have problems with posture unless they are born with an abnormality that predisposes to problems with mobility, such as cerebral palsy, developmental dysplasia of the hip (previously called congenital dislocation of the hip) or a missing limb. However, as children grow older they become more aware of adult habits and often copy them. This is when problems with posture can begin.

Sitting at a computer for long periods also affects the curves of the lower back and neck. Depending on how the head is held while looking at the screen, the other spinal curves alter to try to keep the upper body balanced. For example, in a sitting position, the eyes should be level with the top of the screen so that the head is level. If the head is tilted backwards in order to look upwards, the lumbar spine curvature will be increased, causing both neck and lower back problems. This is why the Health and Safety Executive (see Ch. 13) have regulations about how people should sit when using computers (Box 18.10). The longer people sit at computers in a poor posture, the more likely they are to develop neck, back and other joint problems. It is particularly important for children not to spend too long sitting at a computer because of the damage they can do to their still developing bones and joints. However, the trend for computer games and careers in IT encourages many people to spend long hours at the computer, often without much thought of how this will impinge on their long-term health.

Recommended position for sitting at a computer

These nine steps should be followed when you sit at a computer or workstation:

Student activities

Visit the Working-Well website (www.working-well.org Available July 2006) and work through the exercises there to ensure your workstation is correctly organized.

As two-legged upright beings, humans are constantly at the mercy of gravity trying to pull them nearer to the ground. During the course of a day, people lose height as the spine continually counteracts the effects of gravity on their bodies. Water loss from the intervertebral discs (the pads of cartilage between the vertebrae) is another contributing factor. However, after a night’s sleep the discs swell again and by the morning, height is regained. Therefore, when measuring a patient’s/client’s height and weight (see Ch. 14), it is advisable to do this at the same time of day, so that the same conditions prevail. This is particularly important when children are being assessed and/or treated for problems with growth and development.

Effects of ageing on the spinal curves

As part of the normal ageing process, the effects of gravity begin to take their toll on the musculoskeletal system. The ‘elderly people crossing’ road sign depicts older adults walking with stooped posture and using walking sticks. Although not appropriate for the majority of older adults, this sign clearly demonstrates the combined effects of poor posture and gravity on the musculoskeletal system. There is, however, nothing wrong with stooped posture, as long as the position is not sustained for lengthy periods. Anatomically, the stooped posture is exactly the opposite of upright posture. Muscles work in antagonistic pairs (see p. 509) and when one of the pair is contracting the opposing group relaxes. In the upright posture the muscles classified as extensors (that act to straighten joints) are active, whereas in a stooped posture the flexor muscles (that act to bend joints) are active. Movement between both of these postures is recommended in order to ensure good blood flow to each group of muscles. Regular changes in posture mean that muscle shape also changes between short, fat and tense in the contracted state, to longer, thinner and more pliable in the resting state. This increases blood flow to, through and from the muscles and improves oxygen exchange (see Ch. 17) between the blood and the muscles. At the same time waste products are removed from the muscles. This maintains optimum health of the muscles and their surrounding fascia. Try to move regularly between the upright and slouched postures while reading the rest of this chapter.

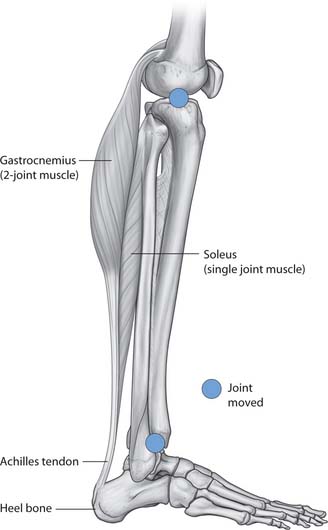

Movement

Movement is brought about by the actions of muscles on joints. Some muscles act on more than one joint and these are the most active in producing movements. Single joint muscles are the deeper, postural muscles (e.g. soleus) and two-joint muscles are the more superficial, active muscles (e.g. gastrocnemius) (Fig. 18.10). This arrangement of muscles helps to produce coordinated movement. For a more detailed explanation of the mechanics and physiology of human movement see, for example, Trew and Everett (2001).

Fig. 18.10 One- and two-joint muscles of the lower leg

(reproduced with permission from Drake et al 2005)

Gait

Gait is the term used to describe the manner in which people walk or run. A person’s gait can be analysed in a laboratory, which can assist in the diagnosis and treatment of mobility problems such as arthritis. Gait varies depending on:

Balance is the key to walking. The balance reflexes do not begin to develop until about 6 months of age and, as toddlers begin to walk around 12–13 months (Wong et al 2001), their gait is quite different from that of adults. Children under the age of about 2 years walk with flat feet and their legs more widely apart. About the age of 4 years, children begin to develop the arm swing. As the more balanced adult gait of striking the ground with the heel first and swinging the arms develops, the pace of step and step length increase. This is often lost in Parkinson’s disease (see Table 18.1). If someone has a particular way of putting one foot down on the ground, then the other foot has to alter its pattern of movement to accommodate for this.

As posture is about maintaining dynamic balance, whatever happens in one part of the body affects the movement in another part. A Trendelenburg gait is characterized by leaning to the affected side every time the opposite leg swings through to take a step, which is caused by unilateral weakness of hip abductor muscles (gluteals). In older people, the pace of walking and the step length generally decrease. Older adults often suffer from gait disorders that have many causes, one of which may be a fear of falling (Alexander & Goldberg 2005).

Age and disability are the two major factors contributing to changes in gait because both affect posture and balance. Degenerative changes around the hip also tend to reduce stride length. People gradually lose the ability to maintain their balance as they age; therefore, in order to provide a larger base for support to maintain balance, the width of the step also increases slightly.

The joints tend to stiffen with age, which reduces the range of movement. If this happens around the ankle it becomes more difficult to lift the foot free from the ground, leading to dragging of the toes that can predispose to falls. Finally, joint stiffness also affects the spine, leading to loss of rotation and arm swing. Reduction in both of these elements slows the walking speed.

Joint problems that affect gait may be reversible with surgical intervention and include arthritic joints, flat foot (pes planus) and bunions (hallux valgus). Foot drop is another cause that results from compression damage to the peroneal nerve caused by, for example, a prolapsed (‘slipped’) intervertebral disc. Joint and muscle pain will affect gait. Pain in the hip(s) or knee(s) causes people to spend less time weight-bearing on the affected joint. Fibromyalgia (muscle, tendon and joint pain) and myasthe-nia gravis (an autoimmune condition) are disorders that both result in weakened and easily fatigued muscles that can impair mobility. Table 18.1 outlines Parkinson’s disease, a common condition that affects both movement and gait. Other terms used to describe problems with movement experienced by patients/clients include:

Many problems with gait can be attributed to problems with the feet, which is why it is important to refer people with foot conditions, especially older adults, to a podiatrist. These include many easily treatable and reversible conditions such as corns and calluses, nail deformities, verrucae, athlete’s foot and other fungal infections.

Efficient handling and moving (EHM)

Many people can be encouraged to move themselves with help, such as verbal encouragement or a hand placed over the muscle groups to be moved, and further intervention is not needed. Good handling and moving skills are paramount to the health and safety of nurses and their patients/clients and are essential to assist people to move safely when they cannot move unaided. Nurses who understand the principles of human movement can apply them not only to care safely for people with mobility problems, but also to protect themselves from injury. Knowing the stages of human development, including ageing, also enables nurses to predict, to some extent, the needs of people of all ages (see Ch. 8).

Details of the current legislation and the principles of safe handling and moving are explained in Chapter 13. This section extends this to include the safe handling and moving of people including:

Another important text to read is The Guide to the Handling of People (Smith 2005). This book details all the moves that can be executed safely (too numerous to mention in this chapter), those that are condemned because they are considered to be a very high risk to nurses and patients/clients, and how equipment can be used to minimize handling and moving injuries. Suggestions are given about the best way of applying the principles of safer moving but it is beyond the scope of this chapter to cover every potential situation that a nurse might come across.

It is important to understand the difference between efficient handling and moving, and effective handling and moving:

Efficient movement is therefore preferable as it is less likely to result in injury to either nurses or patients/clients. Several equally acceptable approaches to EHM are recognized, including:

Principles of safer handling and moving

In order to minimize the risk of injury to either practitioners or patients/clients, it is important always to:

The principles of efficient movement are covered in Chapter 13. Carrying out the exercises in Box 18.11 will remind you of these.

Principles of efficient movement

It is essential that nurses learn to adopt a systematic approach to all interventions that require the handling and moving of people.

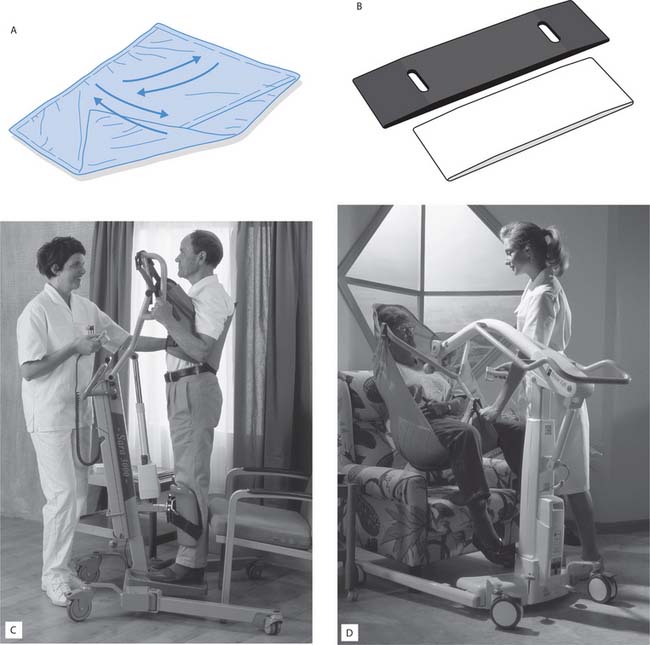

Equipment

There are many devices available to assist in moving people (Fig. 18.11). Commonly used equipment and its potential uses are described below. Use of mobility aids such as walking frames, walking sticks and wheelchairs is explained on page 521.

Fig. 18.11 A range of handling and moving equipment: A. Glide sheet. B. Small transfer boards. C. Standing and raising (SARA) hoist. D. Trixie hoist (hoists reproduced with permission from ARJO)

Glide sheets

Glide sheets, also known as slide sheets (see Fig. 18.11 A) are often used to help people move in bed or in a chair. There are many different styles, but they all work on the same principle of reducing friction between the skin and the bed or chair surface when they are placed under a surface contact area, e.g. the sacrum, heels, shoulders, head. Some glide sheets enable movement to occur in several directions, i.e. up, down, side-to-side and in a circular movement. These are commonly referred to as multiglide sheets, which are made of thin, low-friction material. Others allow movement in one direction only and are referred to as one-way glide sheets. Typically, a glide sheet looks like a sleeping bag, but is open at both ends and has a slippery inner surface. Once in position, it is possible to move a person using minimal force. Some glide sheets have handles to enable the handlers to take hold of the sheet rather than placing their hands on the individual.

Transfer boards

These are generally fairly solid although some are more flexible than others, and are used to assist in transfers between different pieces of equipment or furniture such as chairs, beds, baths, wheelchairs, trolleys and car seats. They are often referred to as lateral transfer boards since the person being moved usually moves in a sideways direction. Depending on the nature of the transfer, a smaller or larger board may be used. Glide sheets are often used in conjunction with transfer boards as they reduce the handler effort required. Some transfer boards are manufactured with glide sheets attached. These can be useful for bathing. Figure 18.11 B. shows a small transfer board used for sitting transfers, while larger transfer boards are available for use in bed transfers.

Hoists

Mechanical and electrical hoists are widely used to assist people into and out of bed and chairs. Mechanical hoists usually require more handler effort to operate than electrical hoists. Another benefit of the electrical hoist is that the patient/client can be given the control box and, following instruction and supervised practice, they can operate it themselves. Many people with paraplegia (who have paralysis and therefore functional loss of their trunk and lower limbs) are able to move themselves independently using electrical hoists. There are many different styles and sizes of hoists and it is important to understand how a particular hoist works before using it to move people.

Some hoists are used only to assist people into a standing position for a short period of time, for example to assist with toileting, or while their personal hygiene is being attended to and/or their clothing is being adjusted.

Standing and raising hoist

Figure 18.11C shows a standing and raising appliance (SARA) hoist, which is used only for standing transfers. These standing hoists should only be used when the person being moved can take some of their body weight through their feet. If there is any doubt about this, standing hoists must be avoided and a passive lift hoist that will take the whole body weight used instead. Each hoist clearly displays a safe weight that must not be exceeded.

Passive lifting hoists

Passive lifting hoists are suitable for use in situations where there is any doubt about a person’s ability either to move or to comply with instructions. Passive lifting hoists involve the use of slings, made of soft but strong material, that are applied to the patient/client before being attached to the hoist. Disposable slings are sometimes used to minimize cross-infection (see Ch. 15); otherwise the slings should be laundered according to the manufacturer’s instructions and local policy. Some slings are also suitable for bathing and toileting. Figure 18.11 D. shows a Trixie hoist with its slings. Slings are not interchangeable and the correct ones for a specific hoist must be used following the manufacturer’s guidelines. Slings are available in a range of sizes and the most appropriate size should be used. A correctly fitted sling adds to the security of a patient/client during the transfer.

There are also hoists that enable people to be raised off the bed while in a lying position. These are used for people with spinal injuries who are not allowed any flexion of the spine and in operating theatres.

Hoists can appear very frightening to people who have never been moved in this way before. Nurses should take time to discuss with patients/clients why they are being moved in this way, describing the benefits to the individual as well as to the nursing staff. Chapter 13 (p. 328) identifies the Health and Safety regulations that must be followed when using equipment such as hoists.

Accessories

Sometimes it is not necessary to use hoists and slides when moving people, and equipment described in this section can be used to assist mobility.

Rope ladders

Rope ladders attached to the end of the bed can be useful for assisting people to move themselves into a more comfortable position independently. Patients/clients need to have good upper limb and head control to be able to pull themselves up into a sitting position.

Turning discs

These consist of two discs that rotate against one another and are designed either for people to sit on or to place under their feet. They are used to assist with turning and can be used independently or with assistance. Generally, it is better to use turning discs with lighter people as the weight of heavier patients/clients can interfere with the turning mechanism.

Using equipment to move people

Nurses must familiarize themselves with any equipment used in people’s homes, nursing homes and wards before using it. It is also useful to have experienced being moved using the equipment so that clear explanations can be given to the patient/client. Practical classes at university provide the opportunity to experience being moved in a hoist while under the watchful eye of a trained supervisor and it is a good idea to use these opportunities. They can also be used to discuss with the trainer if a particular piece of equipment is appropriate for a particular care setting. Observing a demonstration using a healthy volunteer who cannot represent your specific patient’s/client’s needs may not necessarily identify problems with equipment that may be encountered in practice.

Checking equipment

Always check that the equipment is in good working order before using it to move people. Chapter 13 outlines the Lifting Operations and Lifting Equipment Regulations (LOLER) for checking equipment safety on a regular basis. Common faults include:

Risk assessment

Initial assessment of the patient’s/client’s mobility needs must be carried out by an experienced practitioner and appropriately documented in the nursing notes. Physiotherapists and OTs may be involved in this process, which provides a broad indication of the equipment that may be required to move the patient/client. This part of the patient/client records must be read carefully before any handling and moving activities are carried out. If you are unsure about what is expected, it is essential to seek advice from your mentor. This prevents injury to either patients/clients or nurses by carrying out procedures incorrectly (Box 18.12).

Condoning unsafe practice

Jootun and MacInnes (2005) examined the extent to which undergraduate students correctly apply taught principles when handling and moving people during placements. They identified many factors that influence practice and can promote the continuance of unsafe practice. In today’s society where litigation is increasing and patients/clients are more informed about their care and codes of practice, it is important to carefully consider the ethical dilemmas that may arise each time a patient/client is moved.

As there is a possibility of litigation when things go wrong, it is always advisable to err on the side of safety. A person in bed is unlikely to suffer harm by waiting a few minutes longer while the appropriate preparations for moving them are made.

Although an initial assessment will have been undertaken, a patient’s/client’s condition can change at any time. It is therefore important that each time the person is being moved, further assessment of both their needs and the handler’s capabilities is carried out.

Effective communication

Handling and moving people requires effective communication skills (see Ch. 9). Pacing of explanations is important so that too much information is not given at once or causes anxiety or confusion. Children, like anyone else, should not be patronized when equipment is being used; they prefer to be told what is going on and what to expect. For example, telling a child that getting into a hoist is like going on a rocket trip can conjure up an image that may be both frightening and easily misunderstood. People who are frightened do not cooperate easily and inappropriate explanations may lead to breakdown in the nurse–patient/client relationship. Some people are unable to understand explanations about handling and moving equipment, e.g. some clients with dementia or a severe learning disability. In such cases, an empathetic approach and careful handling and moving must be used.

It is good practice to explain what moving a person will involve and to describe any equipment and what it does before bringing it to the bedside. Patients/clients should direct the speed of moving activities. People with poor vision should be encouraged to touch and handle equipment before it is used so they can get a sense of what will be happening to them.

Finding the most suitable equipment

Sometimes it can be difficult to find the ideal piece of equipment to move a patient/client safely, e.g. where there is apraxia or dyspraxia (see p. 513). In these situations physiotherapists must be resourceful in finding and using the right equipment to meet very specific individual needs. Foam wedges, mats and padding are often used to reduce the risk of injury from the equipment itself. These clients can become very agitated and, since they have little or no control over the movements of their limbs, can also be at high risk of injury as can those assisting in the manoeuvre. It is particularly important that only the palms of the hands are used when supporting limbs. Gripping must be avoided as this causes strong contraction of the underlying muscles, making control of the limb even more difficult.

Handling and moving people

This section addresses key issues of moving people with or without equipment. Details about how to carry out specific manoeuvres can be found in the Guide to the Handling of People (Smith 2005). Nursing patients/clients in bed usually involves handling and moving them to carry out their care, for example:

Helping people to move in bed has been identified as carrying a higher risk of injury than other handling and moving activities (Bertolazzi & Saia 1999). For this reason, it is important that all necessary steps are taken to reduce the risk of injury and to follow the handling and moving guidance given in the nursing care plan.

When moving people in beds or chairs it is important to be aware that the spine is the central axis around which all movement occurs. If a patient/client who has lost power of their arms is required to move one of their hands, the nurse should work from the shoulder girdle. This is because the muscles of the shoulder girdle are postural muscles, built for power, rather than the smaller muscles of the hand, which are built for fine movements. If the hand is moved first, the handlers must bear the load of the whole arm, whereas moving the shoulder first allows the arm and hand to be moved with less effort. Likewise, to move a person’s foot, the move is started from the hip.

It is often necessary to support patients’/clients’ limbs on pillows while they are being moved in bed. This must be carried out in a manner that both supports and protects the limb, and does not cause pain. Limbs should be supported underneath, either in the palm of the hand or across the forearm, while pillows are being positioned. The limbs should be supported in natural positions (Fig. 18.12) that do not put joints into positions that could result in pain or loss of function. Feet should not be left hanging off the ends of pillows and wrists should be supported in neutral positions.

Turning a person in bed

This technique is used to move patients/clients in bed to minimize the risk of twisting their spines while changing bed linen, placing hoist slings in position or turning them (to minimize the risk of pressure damage, see Ch. 25). Box 18.13 (p. 520) describes the principles of turning a patient/client in bed using a glide sheet.

Turning a person in bed using a glide sheet

All handling and moving situations should be risk assessed to identify the number of staff and the equipment required.

Regaining balance

When a person has been immobile for a period of time, none of the body systems works to their full potential and a programme of gradual mobilization is required to enable them to regain full independence. After a couple of days in bed with a viral illness, even young people may feel quite wobbly on their legs, dizzy and not up to their usual energy levels, and find carrying out even simple tasks makes them feel tired. The feeling of dizziness experienced after a lengthy period of lying down can be due to postural hypotension. For this reason, people who have been nursed in a supine position (lying flat) are sat up gradually, so that the cardiovascular system can adjust to the new position.

If patients/clients are being nursed on a profiling bed, the head of the bed is gently raised a little at a time. Giving the control box to the patient allows them to raise the head of their bed to a position with which they feel comfortable. They may raise the head of the bed further at a rate they can tolerate, until they are able to sit upright. At this stage they will still need to be supported with pillows and backrests. Thereafter they will need to relearn how to sit up unsupported and regain their sitting balance.

Once sitting balance has been regained, the patient/client can progress to standing and walking. The key points to be aware of are whether or not the patient/client can move from sitting to standing unaided and, once standing, whether or not they will have standing balance. Mobility aids and hoists can be used to assist patients/clients to stand and walk (see p. 520).

Helping a person to sit up in bed

The most efficient equipment to assist a patient to move from the lying to the sitting position is an electric powered, height adjustable, profiling bed. If profiling beds are not available, other equipment can be used on non-profiling beds such as:

Patients/clients can be encouraged to move themselves in bed using equipment designed for the purpose, e.g. rope ladders or slides, or a combination of these.

As patients recover and become more mobile, the nursing care plan is altered to reflect their improving mobility. Patients should be encouraged to help themselves to sit up by rolling onto their sides, taking their weight through their elbows and pushing themselves up into a sitting position. During any of the aforementioned procedures, the nurse should initially stay beside the patient to offer support if needed and to give advice and encouragement. Once patients have gained confidence in carrying out the move, and the nurse is satisfied that they are capable of moving themselves safely, observation can be carried out from a distance.

Helping a person to get out of bed

Ensure that there is enough space to work safely, taking into account the size of the chair and the amount of space required for turning the patient/client. Box 18.14 explains how to select a suitable chair for a patient/client; however, in reality, choice may be limited. Initially the bed should be level with the upper thigh while the patient/client is being dressed. Once the person is ready to be moved into a sitting position the bed is lowered to allow their feet to touch the floor. Always check that the brakes are securely applied before helping a person to move. Do not lean against the bed when moving a person as the wheels may slip on the floor.

Choosing a suitable chair

Tarling (1997) considers that the following factors should be taken into account:

The seat

The back

Well-fitting, lightweight slippers should be put on to prevent the person slipping when their feet reach the floor. Shoes should always be worn with socks, to maintain dignity and to prevent chafing of the feet; however, they can add considerably to the weight of the legs, making them more difficult to move.

The nursing care plan will indicate what equipment to use and how much assistance a patient/client needs to get out of bed and sit in a chair. All equipment requires the assistance of at least one nurse. This includes:

Some patients/clients require only minimal assistance to stand up from the side of the bed. These people must have good sitting balance and be able to support themselves while sitting at the edge of the bed with their feet flat on the floor. Always allow the patient/client to dictate the speed of the move; it is important that people feel in control and that their needs are respected. A person who has had strong analgesics may not be as quick-thinking as usual and needs to be given short, concise instructions that are easily understood. It is also important to be aware that some drugs may cause postural hypotension, a drop in blood pressure that may cause dizziness or fainting when standing upright.

The physiotherapist can provide specific advice to nurses about positioning themselves to help a particular patient/client.

Helping a person to stand up from a chair

Standing a patient up from a chair is different from standing a patient up from a bed. The main differences are that nurses must accommodate the arms of the chair and the height of the chair is usually fixed. Equipment that may be used includes:

Key points to follow when assisting people to stand from chairs are shown in Box 18.15.

Principles for assisting people to stand from chairs

Helping people to mobilize

The differences in gait in children, adults and older people (see p. 513) must be taken into account when assisting people to walk. It can be difficult to walk alongside a patient/client who has an altered gait. Helping people with walking carries an increased risk of injuries (Thomas 2005). Allow people with visual impairment to use familiar arm holds for walking, e.g. taking hold of the sighted person’s left arm around the elbow and walking slightly behind. Equipment used to assist people with walking includes walking sticks, walking frames and crutches. These are all measured and fitted to the person’s height by the physiotherapist or registered nurse. Wheeled walkers may be used for children. If a person needs manual assistance with walking, an assessment is carried out and documented in the care plan. This takes account of whether the individual:

The following factors should be also taken into account and assessed prior to mobilizing a person:

Walking frames

Walking frames are widely used and come in many shapes and sizes according to the function for which they are required. Some walking aids have wheels and are known as rollators. They may have a shopping basket attached so that they can be used to carry light bags. In hospitals, walking frames often have rubber stoppers on the ends of the legs so that the frames do not slip on the floor. Sometimes walking frames are used temporarily as people regain full fitness. For other people, they are a permanent measure to maintain their safety and independence, especially those who:

Walking sticks

Walking sticks or tripods (that have one handle and three feet) provide a similar function to walking frames, but are less bulky. They are often used as a first measure when people become aware that their balance is failing. Many people purchase walking sticks without any advice from a physiotherapist or OT. Most walking sticks are height adjustable and should be set at a comfortable height that allows the elbow to be held in a slightly flexed position. The correct height for the stick is identified by measuring the distance from the person’s wrist to the ground while they are wearing their normal outdoor shoes. Normally the stick is used on the side to which the person is most likely to fall, but this is not a hard and fast rule and physiotherapists or OTs can assist in properly assessing the person to advise on individual requirements. Physiotherapists will also measure clients for crutches and tripods so that they are given the correct height of appliance.

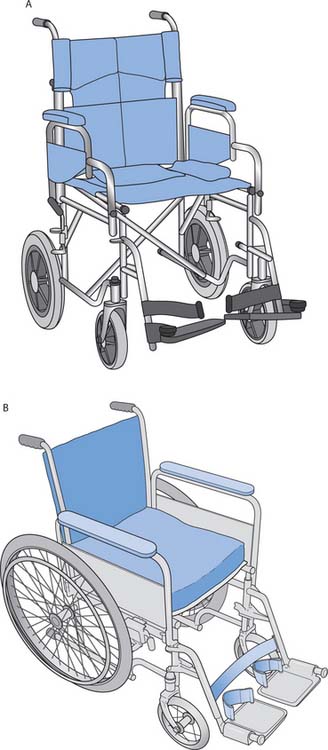

Wheelchairs

Wheelchairs offer a degree of independence to some users, but many others are dependent on being pushed around. It is important to understand what a person’s expectations are when discussing the use of a wheelchair. The following general principles are useful:

Choosing the correct width of wheelchair is important to ensure that the patient/client will not slip out of it. It is also necessary to consider the width of doorways if the wheelchair is for home use. Sometimes it is necessary to remove doors to enable access to rooms. All new buildings must comply with national building regulations, e.g. the Scottish Building Standards Agency (2004), to ensure that they have wheelchair access through at least one door and, thereafter, into at least one toilet and one public room on the ground floor.

Wheelchairs can be designed to suit the specific needs of individual patients/clients. Sometimes the whole seat is moulded around the person’s body to accommodate their body shape and offers support in the correct places such as the head, thorax, hips, knees and feet. Back extensions, head extensions, leg extensions and foot plates can all be adapted to meet the individual patient’s/client’s needs. Many younger people have lightweight frames and wheels on their wheelchairs, particularly if they are likely to be involved in sporting and keep fit activities. Different types of padded seat are available to reduce the effects of pressure (see Ch. 25). Box 18.16 provides information about checking and storage of wheelchairs.

Falls

Cryer and Patel (2001) identified that, in the community, one-third of people over the age of 65 and 50% of people over the age of 80 will fall at some time. Some of these falls will result in fractures. Dealing with a falling patient is challenging. There are many factors that predispose to falls, including:

As falls are common, it is very important to be aware of the main predisposing factors in order to prevent or minimize their occurrence. Prevention of falls is explored in Box 13.9 (p. 326). Older adults who are admitted to hospital following a fall are referred to a gerontologist (a physician who specializes in the care of older adults) for further investigation of their physical health and home circumstances. Falling is often the first indication of an underlying problem. It may be the sign of something simple, e.g. a person requires spectacles, or it may be the result of something more serious such as postural hypotension. Gerontologists carry out physical and psychological investigations to identify the cause of falling and the measures required to remedy the situation.

As part of the multidisciplinary team (MDT), gerontologists work in conjunction with nurses, OTs, physiotherapists and social workers to provide the support needed to enable people to return home. By reducing polypharmacy (see Ch. 22), treating previously undiagnosed conditions and putting appropriate mobility aids into the home, many older adults can be enabled to continue to live at home. The benefits of living at home, in familiar surroundings, far outweigh those of living in supported accommodation, e.g. a nursing home. Moving people from their familiar environment can cause confusion and increase the risk of falls. It is also more cost-effective for health authorities to provide support in people’s homes than in long-term supported care.

Care of people who have fallen

Normally nurses walk to the side and slightly behind patients/clients when they are escorting them (see p. 520). This means that if a patient/client loses their balance, the nurse can move behind them and begin to control their descent to the ground. However, this should only be undertaken if the following criteria are present:

Alternatively, the nurse must clear any furniture if possible and allow the patient/client to fall to the ground, particularly if the person is falling away from the nurse.

Once on the ground the patient/client is safe and the situation must then be assessed to find the best means of assisting them to stand up again. It may be necessary to make a patient comfortable on the ground until the requisite help arrives. People should always be assessed for injuries incurred before being moved.

The patient/client may be able to stand up unaided or be able to follow instructions that will help to do this. Some people will have previously been taught how to do this by the physiotherapist. Small children may be lifted manually, but otherwise inflatable cushions or hoists (see p. 516) should be used if patients cannot assist themselves to stand. An incident form is completed according to local policy (see Ch. 13).

The benefits of mobility and hazards of immobility

In order to maintain good health it is important to exercise regularly as there are many benefits of mobility that are often taken for granted (see below). Both weight-bearing exercise (e.g. walking, running, cycling) and non-weight-bearing exercise (e.g. swimming) should be encouraged. Weight-bearing exercises involve overcoming the effects of gravity and are good for maintaining and developing bone mass (see p. 506). Non-weight-bearing exercises, such as swimming, can also be carried out in a hydrotherapy pool (see Box 18.20, p. 527) where the body weight is supported, the effects of gravity are greatly reduced and the joints can be moved more easily.

Hydrotherapy

Hydrotherapy is the use of water to promote health and wellbeing (Hall et al 1996, Foley et al 2003). The water can be iced, cold, tepid, hot or steam and can also be used as compresses, inhalations or baths. Hydrotherapy has been used since the days of the ancient Greek philosopher Hippocrates who promoted the health benefits of taking a bath.

Cold-based hydrotherapies such as ice packs and cold compresses decrease normal activity, constricting blood vessels and numbing nerve sensation, whereas heat has the opposite effect. Sometimes, treatment involves both cold and heat being applied alternately to a painful area to rapidly promote local circulation.

Exercising painful muscles in a warm hydrotherapy pool is beneficial because water overcomes the effects of gravity, making it easier to move. People do not have to be able to swim to take hydrotherapy. Movements are carried out gently and slowly. The acts of getting into the water and floating, moving the arms or walking through the water help to increase the range of movements and build up muscle strength. A complication of hydrotherapy may be the desire to work too hard! Being in a warm, pain-free environment can lull people into a false sense of security and they may move themselves into a range of movement with which their fascia and muscles are not familiar, causing discomfort. Frequent, short sessions are better than occasional longer sessions.

People with arthritis and chronic back pain benefit from hydrotherapy. Hydrotherapy can also have a calming effect and it is often used for people with learning disabilities and associated dyspraxia.

Sometimes complete immobility is enforced, such as during bedrest or coma, while application of a plaster cast confers immobility of the affected limb. Immobility can be short or long lasting. In these situations it is important to be alert for signs of the many potential hazards of immobility, discussed later in this section. Short-term immobility is less likely to be associated with the potential hazards of immobility. This section explores the benefits of mobility and the potential hazards of immobility across the lifespan.

Benefits of mobility

Keeping mobile is one of the best ways to keep fit. A 20-minute, brisk walk every day will improve the fitness of all body systems, especially the cardiovascular and musculoskeletal systems. Specific health benefits include:

The Paralympics clearly show that exercise and fitness can be accessible to everyone and that many people are able to overcome severe disabilities to keep fit although they need to remain vigilant about the hazards of immobility, especially the development of pressure ulcers.

Children

Play normally provides the exercise that children’s body systems need to grow and develop in a coordinated manner. Further intervention is unnecessary in children who are able to play actively by participating in, for example, cycling, running, ball games and other weight-bearing activities. However, children who have sedentary hobbies such as playing computer games and watching television will begin to feel the effects of lack of exercise. In addition to becoming overweight, normal muscle bulk does not build up and there may be changes to the normal curvature of the spine. These may have lasting effects on children’s health, especially the musculoskeletal system, in later life (see p. 511).

Teenagers

Teenagers also need to exercise and should be encouraged to participate in formal exercise in order to develop their bones and muscles. Weight-bearing activities such as walking, running, dancing, skiing, football and rugby help to increase bone mass during adolescence and delay the loss of bone mass thereafter (see p. 506). During exercise, bones accommodate to the stresses that are applied to them, so that those who exercise regularly have denser bones containing more minerals. Bones alter in shape as extra material is laid down at the points of maximum stress. Swimming is an excellent pastime for health in general but, as it is not a weight-bearing activity, it does not affect bone mass. It is, however, very good for developing muscle tissue and the cardiovascular system.

Aerobic, anaerobic and resistance exercises are all good for promoting general health and well-being. Aerobic exercises involve using large muscle groups, rhythmically, over a period of at least 15–20 minutes, and the muscles have sufficient oxygen to fully utilize fuel molecules and release the energy required for contraction. These exercises are generally low in intensity and long in duration such as walking, cycling, jogging or swimming. Anaerobic exercises require muscles to work very hard in the absence of oxygen and are usually high in intensity and short in duration, e.g. sprinting, squash. The limited duration of this type of exercise is due to the accumulation of lactic acid because fuel molecules cannot be fully utilized without oxygen. Resistance exercise – also called strength training or weight training – increases muscle strength, mass and tone.

Cross-training, i.e. training for different events at the same time, such as cycling, swimming and running, develops all the body muscles at the same rate and people report fewer injuries during exercise. In addition, greater body flexibility is present because one group of muscles is not being built up at the expense of others. Cross-training for any sport prevents people from becoming muscle-bound, which can lead to injury (Stamford 1996). For example, runners who only exercise to build up their stamina for running often find their hard-worked muscles become prone to sprains and tendons prone to inflammation. Their other muscles become weaker in comparison and are therefore more prone to injury. This is seen when Olympic athletes, who have spent years training for a particular event, pull up with a calf or hamstring (the posterior thigh muscles) injury in the most important race of their lives.

Adults and older adults

As people age, the benefits of exercise continue to increase (Box 18.17). The more the muscles and fascia have adapted to postural habits, the less flexible people become (see p. 505).

Exercise and older adults

The Department of Health (DH 2004) recognizes the importance of exercising in people of all ages, including older adults, and there are many ways in which communities meet this need:

Student activities

[Resources: Department of Health 2004 At least five a week: evidence on the impact of physical activity and its relationship to health – www.dh.gov.uk/PublicationsAndStatistics/Publications/PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance/PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance-Article/fs/en?CONTENT_ID=4080994&chk=1Ft1Of; MedlinePlus. Exercise for seniors – www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/exerciseforseniors.html All available July 2006]

Hazards of immobility

There are many and diverse hazards of immobility, as listed in Box 18.18. The effects of immobility are the same across the lifespan, but children tend to recover more quickly from a period of immobility.

It is very important for nurses to recognize the potential hazards that patients/clients with limited mobility or who are immobile may face in order to minimize their occurrence. The reasons that people may be at risk from these potential problems are not only physical but also include mental health problems such as depression. In general, the risk of these hazards increases with a person’s age, presence of other health problems and the period of immobility. Bedrest, which confines patients to bed, is sometimes prescribed for therapeutic reasons, for example:

Following a period of bedrest or restricted mobility, a programme of planned return to full activity may be required. This often involves several members of the MDT, especially the physiotherapist and OT whose roles are described. Falls pose a potential risk in many situations and helping people who have fallen is explained at the end of this section.

Maintaining healthy joints and muscles

When not used, the joints stiffen and the skeletal muscles waste, and both will limit mobility when mobility can be restarted. It is therefore important to maintain the range of movements available at joints and the condition of skeletal muscles when mobilization is not possible. Active and passive exercises can be carried out in bed in these situations. Active exercises are those initiated by people themselves without aid, e.g. flexing and extending the fingers. Passive exercises are those initiated by carers who move a person’s joints through the normal range of movements. It is important to know the normal movements at joints so that they are not moved into abnormal and potentially harmful positions. They help to:

Active exercises

Whenever possible, people are encouraged to actively exercise all their joints. Encouraging patients/clients to meet their own hygiene needs, dress themselves and walk around are all good ways of encouraging active exercises. Safety is always important and it may therefore be appropriate to stay nearby so that patients/clients are not over-reaching, e.g. to pick things up, which may affect their balance and result in a fall. When caring for older adults, it is important that they are given enough time to carry out such activities. When nurses intervene too quickly or provide too much assistance, this not only reduces people’s capacity for self-care but also increases dependence on others. Sometimes physiotherapists organize classes that promote movement and provide regular exercise.

Patients/clients who are confined to bed can often still carry out active exercises but may need encouragement to move each joint through its full range of movement on a regular basis during waking hours. In addition to keeping the joints and their associated muscles functioning, carrying out active exercises also helps to pass time and gives people some active control over their recovery. Some patients may wish to use weights in order to provide resistance and make the muscles work harder, or they may be taught specific exercises by the physiotherapist. Patients who have undergone mastectomy (removal of breast tissue) or surgery to the elbow should be encouraged to brush their hair using the affected arm to keep the associated shoulder in good condition. Some patients prefer to have the screens drawn round their bed while they are exercising; always check with the patient first.

Passive exercises

Passive exercises are usually carried out by the physiotherapist, nurse or sometimes the patient themselves (see p. 526). When carrying out passive exercises, the joint is supported proximally (towards the centre of the body) and distally (away from the centre of the body) in the palms of the hands and is moved gently within a given range. Over time, the range of movement (ROM) is increased. Often the patient can resume active exercises, but sometimes active movement may never return, e.g. in a person with paraplegia. It is essential that any passive movement applied to a joint and its associated muscles is carried out gently, assessing (‘sensing’), through touch, the range of movement available at the joint. As soon as resistance to a movement is felt, or the patient expresses discomfort, the joint is returned to its normal resting position (see Fig. 18.12). It is important that the elbow joint is not passively stretched, as it is easily damaged. You must observe a skilled practitioner performing passive movements before attempting them yourself.

Prevention of deep vein thrombosis

Deep vein thrombosis (DVT) occurs when the flow of blood through the deep veins of the legs and pelvis is slowed and blood clots form within those veins. Damage to blood vessel walls and coagulation problems are also implicated in DVT formation, which sometimes occurs in healthy people on long haul flights, causing ‘economy class syndrome’. DVT is dangerous because fragments of the clot may become detached and travel in the veins, through the right side of the heart and lodge in a pulmonary artery in lungs causing pulmonary embolism, which can be fatal. The risk of DVT is reduced by carrying out active or passive exercises (see above) and preventing dehydration (see Ch. 19) during periods of immobility.

Preventing chest infection

When mobility is restricted, the benefits of deep breathing that occur during exercise are lost and deep breathing must be actively encouraged. The aim of deep breathing exercises is to improve the flow of air to the bases of the lungs so that they are well ventilated. This helps to prevent the build-up of fluid or respiratory tract secretions within the lungs and the development of a chest infection. Deep breathing (see Ch. 17) also encourages the coughing reflex, which helps to clear the air passages of sputum and potential pathogens (see Ch. 15). Deep breathing exercises are encouraged in patients/clients who are confined to bed or a chair and in those who can walk only short distances.

Pressure ulcers

This complication of immobility, which is almost always preventable, is discussed in depth in Chapter 25. Nursing intervention is key to the prevention of pressure ulcers.

Constipation

Constipation can be prevented by anticipating the dietary and fluid needs of immobile patients/clients and providing an appropriate intake. Peristalsis (the contraction of smooth muscle that moves contents along the digestive tract) is reduced when mobility is limited, predisposing to constipation. The diet should be high in fibre to stimulate peristalsis. In adults, 1.5–2 litres of fluid are required daily to maintain hydration and achieving this can be a nursing challenge (see Ch. 19). Prevention and management of constipation is discussed in Chapter 21.

Maintaining well-being