Medical Nutrition Therapy for Rheumatic Disease

Sections of this chapter were written by Kristine Duncan, RD for the previous edition of this text.

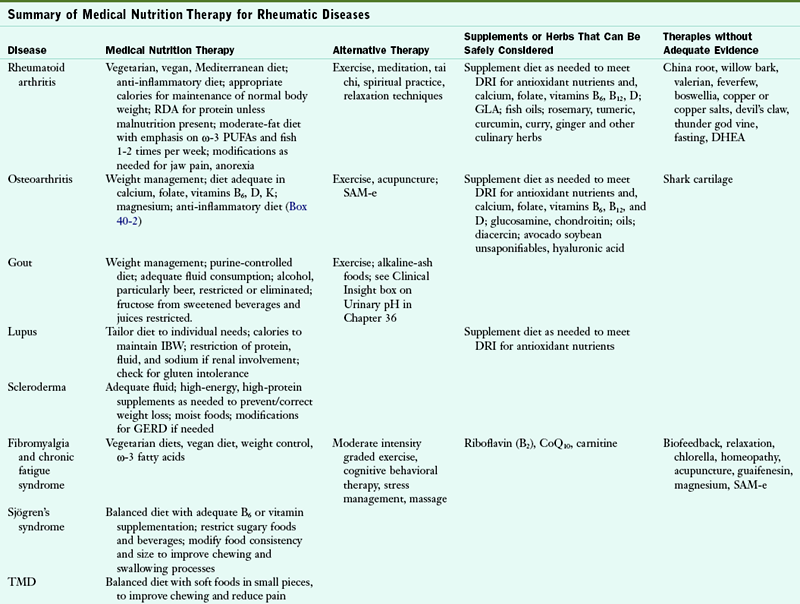

Rheumatic disease and related conditions include more than 100 different manifestations of inflammation and loss of function of connective tissue and supporting body structures, including joints, tendons, ligaments, bones, muscles, and sometimes internal organs. Rheumatic disease is thought to have an autoimmune component. Because no identifiable cause or cure is known, pharmacotherapy, physical and occupational treatment, and medical nutrition therapy (MNT) play important roles in managing the symptoms. Table 40-1 provides an overview of the disorders and their management.

TABLE 40-1

Summary of Medical Nutrition Therapy for Rheumatic Diseases

DHEA, Dehydroepiandrosterone; DRI, Dietary reference intake; GERD, gastroesophageal reflux disease; GLA, Gamma-linolenic acid; IBW, ideal body weight; PUFA, polyunsaturated fatty acid; RDA, recommended dietary allowance; SAM-e, S-adenosyl-L-methionine; TMD, temporomandibular disorder.

Rheumatic disease affects all population groups. According to the National Arthritis Data Workgroup, osteoarthritis (OA) affects 27 million Americans; gout, 3 million; fibromyalgia, 5 million; rheumatoid arthritis (RA), 1.5 million; Sjögren’s syndrome (SS), 1 to 4 million; and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), 161,000 to 322,000 (Helmick et al., 2008; Lawrence et al., 2008). Estimates for the number of people in the United States with systemic sclerosis is 49,000. Arthritis and the related disorders are among the most prevalent chronic disease conditions in the United States and are associated with total direct and indirect costs to the U.S. economy of $128 billion per year in medical care and lost wages (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2007).

Arthritis is a generic term that comes from the Greek word Arthro, which means “joint,” and the suffix -itis, which means “inflammation.” There are two distinct categories of disease: systemic, autoimmune rheumatic disease and nonsystemic OA. The more debilitating and autoimmune arthritis group includes RA, juvenile rheumatoid arthritis, gout, SS, fibromyalgia, SLE, and scleroderma. The OA group includes OA, bursitis, and tendonitis. Other rheumatic diseases include spondyloarthropathies, polymyalgia rheumatica, and polymyositis.

Body changes associated with aging—including decreased somatic protein, body fluids, and bone density, and an increase in total body fat—may contribute to the onset and progression of arthritis. The aging body mass causes changes in neuroendocrine regulators, immune regulators, and metabolism, which affect the inflammatory process. Therefore recent increases in the frequency of these conditions may be the result of aging of the U.S. population. By 2030 approximately 20% of Americans (approximately 72 million people) will be older than 65 years and subsequently will be at high risk for rheumatic disease (National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases [NIAMS], 2006).

Unfortunately, the cause of most rheumatic conditions remains unknown. In addition, some forms of rheumatic conditions can affect other organs such as the skin or blood vessels. Rheumatic conditions have no known cure and are usually chronic, but may present as acute episodes with short or intermittent duration. Chronic arthritic conditions are associated with alternating periods of remission without symptoms, and flares with worsening symptoms that occur without any identifiable cause. Risk factors include repetitive joint injury, inherited cartilage weakness, genetic susceptibility, family history, gender, and environmental factors.

Pathophysiology and Inflammation

Inflammation plays an important role in health and disease. The inflammatory process normally occurs to protect and repair tissue damaged by infections, injuries, toxicity, or wounds via accumulation of fluid and cells. Once the cause is resolved, the inflammation usually subsides. Whether inflammation is due to stress on the joints (OA) or to an autoimmune response (RA), an uncontrolled inflammatory reaction causes more damage than repair.

Polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) play an important role in inflammation as precursors of a potent group of modulators of inflammation termed eicosanoids (eicos means “20” in Greek). Eicosanoids include the prostaglandins (PGs), thromboxanes (Txs) and leukotrienes (LTs) among others. PG and Tx are the product of the enzyme cyclooxygenase (COX) and are termed prostanoids, whereas LTs are the product of the enzyme lipoxygenase. For the synthesis of prostanoids, the COX reaction consumes two double bonds from the original PUFA, whereas lipoxygenase reaction consumes none (Box 40-1; see Chapter 6).

Depending on the PUFA used as substrate, different eicosanoids are produced: arachidonic acid (ARA) (20:4, ω-6) is the precursor of the series 2 of PG and Tx, and the series 4 of LT. If eicosapentaenoic acid (20:5, ω-3) is the substrate, series 3 of PG and Tx and series 5 of LT are produced. Finally, dihomo-γ-linoleic acid (DGLA) (20:3, ω-6) is the precursor of series 1 of PG and Tx, and of series 3 of LT.

The series 2 compounds (PG2 and Tx2) are the most abundant because ARA is abundant in plasma membranes of cells involved in inflammation (macrophages, neutrophils, fibroblasts), and are the most potent inflammatory eicosanoids. On the other hand, PG1 and Tx1, derived from DGLA, have antiinflammatory activities. Thus diets enriched with PUFAs that enhance the synthesis of antiinflammatory prostanoids are, at least theoretically, desirable for the long-term management of rheumatic disease, but usually do not replace the use of medications.

Medical Diagnosis and Treatment

A thorough history of symptoms and a detailed physical examination are the cornerstones for an accurate diagnosis. However, laboratory testing can help to further refine the diagnosis and identify appropriate treatment.

Biochemical Assessment

Acute-phase proteins are plasma proteins whose concentration increases of more than 25% during inflammatory states. Two acute-phase proteins traditionally used to screen for and monitor rheumatic disease are rheumatoid factor (RF) and C-reactive protein (CRP), although they are nonspecific and may also indicate an infection or even a recent cardiac event. The term RF is used to refer to a group of self-reacting antibodies (an abnormal IgM against normal IgG), found in the sera of rheumatic patients. The American College of Rheumatology (ACR) recommends periodic measurements of RF and CRP in addition to a detailed assessment of symptoms and functional status, and radiographic examination to determine the current level of disease activity in these patients.

Antinuclear antibodies (ANA) appear to be present in many autoimmune diseases and can assist with proper diagnosis when used correctly; antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies and myositis-specific antibodies can provide information about the presence of rheumatic disease as well. Measurements of RF and anticyclic citrullinated peptide antibodies may provide unique data in the management of RA (Colgazier and Sutej, 2005). Routine blood testing can include complement, a complete blood count, creatinine, hematocrit, and a white blood cell count, in addition to analysis of urine or synovial fluid secreted by the synovial membrane in the joints.

Pharmacotherapy

Many of the drugs used in treating rheumatic diseases provide relief from pain and inflammation, with hopes of controlling symptoms rather than providing a cure. Analgesics such as acetaminophen (Tylenol) are effective pain relievers. Drugs commonly used to reduce inflammation affect the synthesis of PGs by inhibiting COX activity, thus diminishing PG production. Glucocorticoid therapy decreases the release of ARA from cell membrane phospholipids by binding to the receptor in the cell cytoplasm. This forms a complex that moves into the nucleus as a transcription factor and interferes with expression for the enzyme phospholipase.

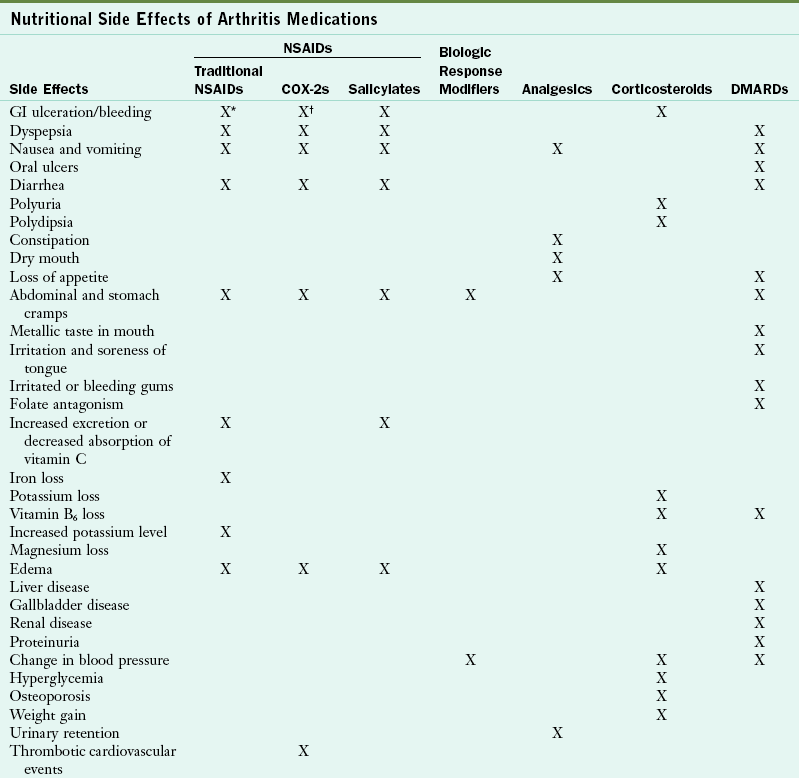

Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), which include ibuprofen (Advil or Motrin) and naproxen (Aleve), slow down the body’s production of PGs by inhibiting COX-1 enzyme activity. They are considered useful tools in the management of most rheumatic disorders; however, long-term use of NSAIDs may cause gastrointestinal problems such as gastritis, ulcers, abdominal burning, pain, cramping, nausea, gastrointestinal bleeding, or even renal failure (Table 40-2; see Chapter 9 and Appendix 31). COX-2 inhibitors (COX-2 selective NSAIDs) such as celecoxib (Celebrex) have been shown to provide relief comparable to other NSAIDs with potentially less gastrointestinal and cardiovascular toxicity. Naproxen and celecoxib appear to be safer than other NSAIDs (Food and Drug Administration, 2005).

TABLE 40-2

Nutritional Side Effects of Arthritis Medications

COX, Cyclooxygenase; DMARD, disease-modifying antirheumatic drug; GI, gastrointestinal; NSAID, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug.

*Less with diclofenac sodium with misoprostol, but increased risk of abdominal pain and diarrhea.

†Less than traditional NSAIDs.

Data from ACR: Guidelines for the management of rheumatoid arthritis, Arthritis Rheum 46:2, 2002; Arthritis Foundation: Arthritis today, 2005 drug guide; Boullata JI, Armenti VT, editors: Handbook of drug-nutrient interactions, Totowa, NJ, 2004, Humana Press.

Biologic response modifiers are a class of drugs that selectively target different elements of the disease, and include those directed against interleukin (IL)-1 such as anakinra (Kineret), or against tumor necrosis factor (TNF)–α, like adalimumab (Humira), etanercept (Enbrel), and infliximab (Remicade). These molecules are administered by injection (vein or subcutaneous) because they are proteins and oral administration would destroy their biologic activities. The main drawback is their high cost, as high as $30,000 dollars per patient per year (American College of Rheumatology [ACR], 2006). Patients taking these drugs should be monitored for chronic infections.

Corticosteroids (cortisone [Cortone], prednisone [Deltasone], methylprednisolone [Medrol], and hydrocortisone [Cortef]) suppress the immune system and decrease inflammation, making them desirable treatments for many of the rheumatic diseases. Possible side effects of corticosteroids include hypertension, hyperglycemia, weight gain, and osteoporosis. Low-dose steroids control most of the inflammatory features of early polyarticular RA. Dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA), a hormone made by the adrenal glands, has failed to show efficacy.

As the most potent of the antiinflammatory drugs used to treat RA, steroids have extensive catabolic effects that can result in negative nitrogen balance. Hypercalciuria and reduced calcium absorption can increase the risk of osteoporosis (see Chapters 9 and 25). Concomitant calcium (1 g/day) and vitamin D (at least 1000 IU/day) and monitoring of bone status may be suggested to minimize osteopenia. Care must be taken to avoid serum calcium levels greater than 11 mg/dL and 25-OH vitamin D levels less than 35 ng/mL. Edema often occurs and may require diet modification, including a sodium- and fluid-restricted diet. Other side effects of steroid use include cushingoid syndrome and gastrointestinal bleeding.

Unconfirmed Therapies

Because modern medicine cannot promise a cure or even permanent relief of symptoms, many persons turn to alternative approaches for help. With growing access to the Internet, patients have a greater exposure to remedies and controversial treatments. In a recent survey, rheumatologists in the United States showed a widespread favorable opinion toward many alternative therapies for patients with rheumatic diseases (Manek et al., 2010).

Favorable effects of self-help treatments are often reported anecdotally, but as a rule no cause-and-effect relationships are documented. Any amelioration can usually be attributed to the placebo effect or to characteristic cycles of worsening followed by periods of improvement. Therapies that are scientifically proven safe and effective can be promoted, whereas caution is needed in regard to therapies for which the science is limited.

Some remedies have their roots in medicine. Salicylates in aspirin are derived from willow bark; they have been around as a medicinal remedy for pain and inflammation for centuries. Willow bark and ginger may relieve pain because their chemical composition is similar to NSAIDs, but excessive blood thinning is a concern (Marcus, 2005). Additional research is needed on valerian, feverfew, boswellia, and curcumin before recommendations can be made for their usefulness in treating RA (National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine [NCCAM], 2009).

Although much of the dietary experimentation is harmless except for the costs, some self-treatment modalities can be harmful. It is best to avoid copper or copper salts, shark cartilage, devil’s claw, echinacea, guaifenesin, alfalfa, wild yam, and methylsulfonylmethane (MSM). Both comfrey and alfalfa are herbs that have been promoted as potential cures for arthritis, yet both have been deemed toxic by the scientific community. Meditation, tai chi, relaxation techniques, thermotherapy and spiritual practice may offer pain reduction. Biofeedback, relaxation, chlorella supplements, magnet therapies, homeopathy, botanical oils, and dietary modifications need further study before general recommendations can be made.

Osteoarthritis

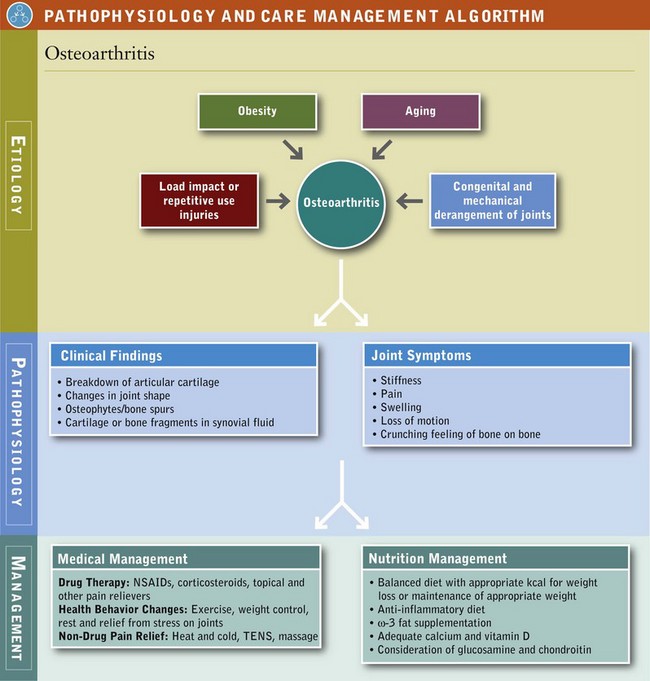

Osteoarthritis (OA), formally known as degenerative arthritis or degenerative joint disease, is the most prevalent form of arthritis. Obesity, aging, female gender, white ethnicity, greater bone density, and repetitive-use injury associated with athletics have been identified as risk factors. OA is not systemic or autoimmune in origin, but involves cartilage destruction with asymmetric inflammation. It is caused by joint overuse, whereas RA is a systemic autoimmune disorder that results in symmetric joint inflammation.

Pathophysiology

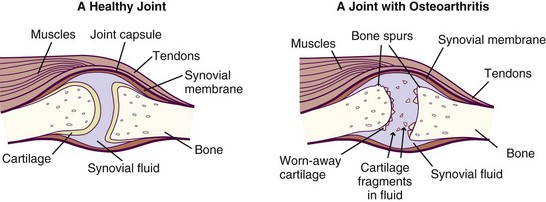

OA is a chronic joint disease that involves the loss of habitually weight-bearing articular (joint) cartilage. This cartilage normally allows bones to glide smoothly over one another. The loss can result in stiffness, pain, swelling, loss of motion, and changes in joint shape, in addition to abnormal bone growth, which can result in osteophytes (bone spurs) (Huskisson, 2008) (see Figure 40-1 and the Pathophysiology and Care Management Algorithm: Osteoarthritis).

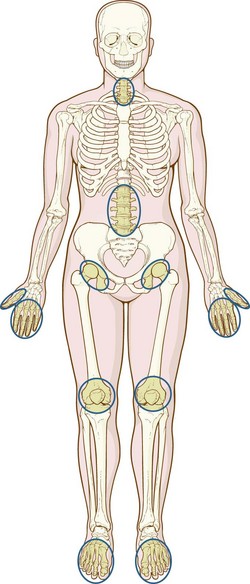

The joints most often affected in OA are the distal interphalangeal joints, the thumb joint, and, in particular, the joints of the knees, hips, ankles, and spine, which bear the bulk of the body’s weight (Figure 40-2). The elbows, wrists, and ankles are less often affected. OA generally presents as pain that worsens with weight bearing and activity and improves with rest, and patients often report morning stiffness or “gelling” of the affected joint after periods of inactivity. Diseases of the joints influenced by congenital and mechanical derangements may contribute to OA as well. Inflammation occurs at times but is generally mild and localized.

FIGURE 40-1 A healthy joint and a joint with severe osteoarthritis. (From National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases: Handout on health: osteoarthritis, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services, NIH Publication Number 06-4617, July 2002, revised May 2006.)

Medical and Surgical Management

The patient’s medical history and level of pain should determine the most appropriate treatment. This should include nonpharmacologic modalities (patient education, physical and occupational therapy), pharmacologic agents, and surgical procedures with the goals of pain control, improved function and health-related quality of life, and avoidance of toxic effects from treatment (Huskisson, 2010). Weight loss and/or achievement of ideal body weight (body mass index [BMI] of 18.5-24.9) should be part of the medical treatment as it improves OA dramatically. See Chapter 22.

Patients with severe symptomatic OA pain who have not responded adequately to medical treatment and who have been progressively limited in their activities of daily living (ADLs), such as walking, bathing, dressing, and toileting, should be evaluated by an orthopedic surgeon. Surgical options include arthroscopic debridement (with or without arthroplasty), total joint arthroplasty, and osteotomy. Surgical reconstruction has been quite successful but should not be viewed as a replacement for overall good nutrition, maintenance of healthy body weight, and exercise.

Exercise

OA limits the ability to increase energy expenditure through exercise. It is critical that the exercise be done with correct form so as not to cause damage or exacerbate an existing problem. Physical and occupational therapists can provide unique expertise for OA patients by making individualized assessments and recommending appropriate exercise programs and assistive devices, in addition to offering guidance regarding joint protection and energy conservation. Nonloading aerobic (swimming), range-of-motion, and weight-bearing exercises have all been shown to reduce symptoms, increase mobility, and lessen continuing damage from OA. Nonweight-bearing exercise may also serve as an adjunct to NSAID use (Egan and Mentes, 2010).

Sports or strenuous activities that subject joints to repetitive high impact and loading increase the risk of joint cartilage degeneration. Therefore increased muscle tone and strength, correct form, general flexibility, and conditioning will help protect these joints in the habitual exerciser. A walking program and lower-extremity strength training are beneficial for individuals with knee OA (Zhang et al., 2008).

Medical Nutrition Therapy

Weight and Adiposity Management

Excess weight puts an added burden on the weight-bearing joints. Epidemiologic studies have shown that obesity and injury are the two greatest risk factors for OA. The risk for knee OA increases as the BMI increases. Controlling obesity can reduce the burden of OA through both disease prevention and improvement in symptoms (Holliday et al., 2010). A well-balanced diet that is consistent with established dietary guidelines and promotes attainment and maintenance of a desirable body weight is an important part of MNT for OA.

Anti-Inflammatory Diet

Recently, the anti-inflammatory diet, a diet resembling the Mediterranean diet, has been useful (Marcason, 2010) (Box 40-2). The diet aims for variety, the inclusion of as much fresh food as possible, the least amount of processed foods and fast food, and an abundance of fruits and vegetables. When combined with moderate exercise, diet-induced weight loss has been shown to be an effective intervention for knee OA (Egan and Mentes, 2010). There is also an anti-inflammatory effect from weight loss in OA management because the reduced fat mass results in the presence of less inflammatory mediators from adipose tissue (see Chapter 22).

Vitamins and Minerals

Cumulative damage to tissues mediated by reactive oxygen species has been implicated as a pathway that leads to many of the degenerative changes seen with aging. However, large doses of dietary antioxidants, including vitamin C, the tocopherols (vitamin E), β-carotene, and selenium have shown no benefit for the management of symptomatic OA (Canter et al., 2007; Rosenbaum et al., 2010).

Many patients with OA consume deficient levels of calcium, and vitamin D. Low serum levels of vitamin D are being studied for their role in OA progression (McAlindon and Biggee, 2005). Improving intake to at least dietary reference intake (DRI) levels is important. Comprehensive nutrition interviewing and counseling should include a determination of acceptable sources of all nutrients for the OA patient, as well as supplementation of the diet to achieve the recommended levels with special attention given to vitamin B6, vitamin D, vitamin K, folate, and magnesium.

Alternative Therapies

A variety of alternative therapies have been proposed to manage pain in OA, including topical aids, manipulative therapies, and acupuncture. Capsaicinoids, derived from chili peppers, have a fatty acid receptor that stimulates, then blocks, small-diameter pain fibers by depleting them of the neurotransmitter substance P, thought to be the principal chemomediator of pain impulses from the periphery. Capsaicin, applied with glyceryl trinitrate to reduce onsite burning, can reduce pain in OA patients (Kosuwon, 2010). Certain pulsed electromagnetic fields can also affect the growth of bone and cartilage with potential use in OA, and use of static magnets may provide temporary pain relief under certain circumstances (Pittler et al., 2007).

According to the Arthritis Foundation (AF), S-adenosyl-L-methionine (SAM-e) has also shown promise for reducing pain and improving mobility in people with OA at doses of 600 to 1200 mg/day, but should not be taken without a doctor’s supervision (Arthritis Foundation [AF], 2007). A systematic review and meta-analysis also found benefit for OA patients treated with acupuncture (Kwon et al., 2006).

Other alternative therapies used to help lessen the need for medication are glucosamine sulfate, chondroitin sulfate, oils, and herbs. Other modalities include diacerein, avocado soybean unsaponifiables, and hyaluronic acid that have a symptomatic effect and low toxicity, but overall effects are small (Zhang et al., 2007). Advocates of these alternative modalities cite reports of progressive and gradual decline of joint pain and tenderness, improved mobility, sustained improvement after drug withdrawal, and a lack of toxicity associated with short-term use of these agents (AF, 2005a).

Glucosamine and Chondroitin

Sodium chondroitin sulfate (chondroitin sulfate) and glucosamine hydrochloride (glucosamine) are both involved in cartilage production, but their mechanism for eliminating pain has not been identified. Limited data suggest that glucosamine sulfate administered orally, intravenously, intramuscularly, or intraarticularly may produce a gradual and progressive reduction in joint pain and tenderness, as well as improved range of motion and walking speed (Huskisson, 2008). Glucosamine has produced consistent benefits, including greater than 50% improvement in symptom scores in patients with OA. In some cases glucosamine may be equal or superior to ibuprofen (McAlindon and Biggee, 2005). Together glucosamine and chondroitin rank third among all top-selling nutritional products in the United States.

The National Institutes of Health (NIH) undertook the Glucosamine/Chondroitin Arthritis Intervention Trial (GAIT), the first, large-scale, multicenter clinical trial in the United States to test the effects of these supplements on knee OA. A dose of 1500 mg of glucosamine (500 mg, three times daily) with 1200 mg of chondroitin (400 mg, three times daily) resulted in statistically significant pain relief for a small subset of participants who had moderate to severe pain, but not for those in the mild pain subset. Compared with 54% of those taking placebo, 79% of those taking glucosamine and chondroitin reported a 20% or greater reduction in pain. Because of the small sample size, these findings are considered preliminary (National Institutes of Health [NIH], 2008). Although it is not effective for all afflicted individuals, a safe dose of glucosamine and chondroitin sulfate is 1500 mg/day and 1200 mg/day in divided doses, respectively (AF, 2005a). GAIT and other studies have found no change in glucose tolerance (NIH, 2006). A metaanalysis report that looked at more than 3000 human subjects found no adverse effects of oral glucosamine administration on blood, urine, or fecal parameters and no serious or fatal side effects (Anderson et al., 2005). In contrast, chondroitin is chemically similar to commonly used blood thinners and could cause excessive bleeding if used in combination with blood thinners. Chondroitin may also elicit a reaction in those with shellfish allergies.

Rheumatoid Arthritis

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a debilitating and frequently crippling autoimmune disease with overwhelming personal, social, and economic effects. Although less common than OA, RA is usually more severe. RA affects the interstitial tissues, blood vessels, cartilage, bone, tendons, and ligaments, as well as the synovial membranes that line joint surfaces. RA occurs more frequently in women than in men. The peak onset commonly occurs between 20 and 45 years of age.

Numerous remissions and exacerbations generally follow its onset, although for some people it lasts just a few months or years and then goes away completely. Although any joint may be affected by RA, involvement of the small joints of the extremities—typically the proximal interphalangeal joints of the hands and feet—is most common (Figure 40-3).

FIGURE 40-3 A patient with advanced rheumatoid arthritis. The twisted hands and the puffiness of the metacarpal joints are typical of the disease. (From Damjanov I: Pathology for the health-related professions, ed 3, Philadelphia, 2006, Saunders.)

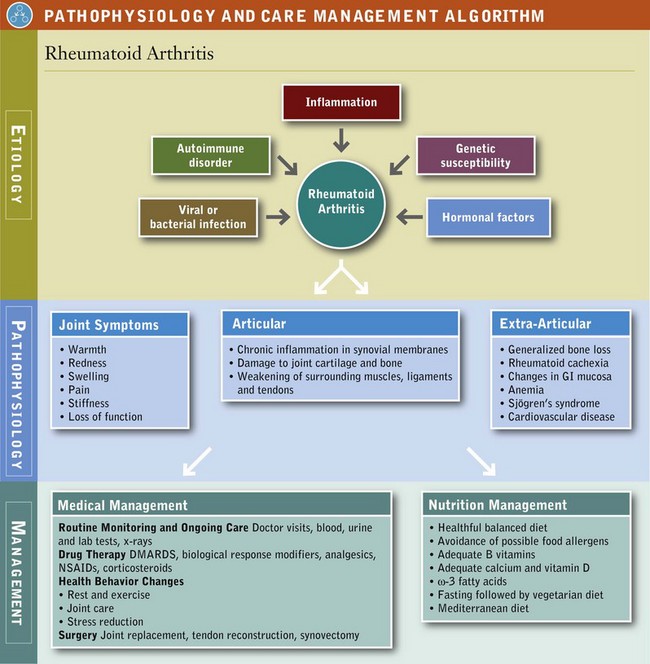

Pathophysiology

RA is a chronic, autoimmune, systemic disorder in which cytokines and the inflammatory process play a role. RA has articular manifestations that involve chronic inflammation that begins in the synovial membrane and progresses to subsequent damage in the joint cartilage (Pathophysiology and Care Management Algorithm: Rheumatoid Arthritis). Although the exact cause of RA is still unknown, certain genes have been discovered that play a role. The likely trigger is a viral or bacterial infection. It has been suggested that drinking large amounts of tea may increase the risk of developing RA (Walitt et al, 2010); however, other studies have suggested that teas are protective. More research is clearly needed.

Medical Management

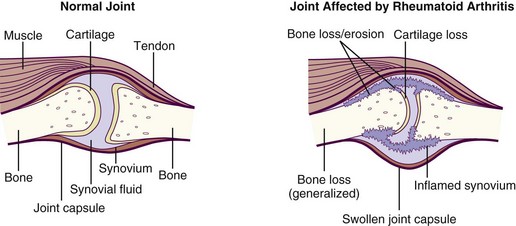

The appearance of rheumatoid factor (RF), may precede symptoms of RA. Pain, stiffness, swelling, loss of function, and anemia are common. The swelling or puffiness is caused by the accumulation of synovial fluid in the membrane lining the joints and inflammation of the surrounding tissues (Figure 40-4).

FIGURE 40-4 Comparison of a normal joint and one affected by rheumatoid arthritis, which has swelling of the synovium. (From National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases: Handout on health: rheumatoid arthritis, NIH Publication Number 04-4179, January 1998, Revised May 2004. National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services.)

RA patients are at increased risk for cardiovascular disease, explained by the systemic inflammatory response (Snow and Mikuls, 2005). This is especially significant considering findings regarding COX-2 selective NSAIDs. In fact, many of the drugs used to treat RA can result in hyperhomocysteinemia, hypertension, and hyperglycemia, all risk factors for cardiovascular disease. Conveniently, treatment aimed at reducing inflammation may benefit both diseases (Snow and Mikuls, 2005).

Pharmacologic Therapy

Medications to control pain and inflammation are the mainstay of treatment for RA. Salicylates and NSAIDs are often the first line of treatment, and methotrexate (MTX) is commonly prescribed as well, but these drugs may cause significant side effects. The choice of drug class and type is based on patient response to the medication, incidence and severity of adverse reactions, and patient compliance. Drug-nutrient side effects can occur with any of the drugs. Side effects of drug use may influence ingestion, digestion, and absorption, and hence nutrition status. See Chapter 9 and Appendix 31.

Salicylates are commonly used. However, chronic aspirin ingestion is associated with gastric mucosal injury and bleeding, increased bleeding time, and increased urinary excretion of vitamin C. Taking aspirin with milk, food, or an antacid often alleviates the gastrointestinal symptoms. Vitamin C supplementation is prescribed when serum levels of ascorbic acid are abnormally low. See Appendix 30.

Disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) may be prescribed because of their unique ability to slow or prevent further joint damage caused by arthritis. These include MTX, sulfasalazine (Azulfidine), hydroxychloroquine (Plaquenil), azathioprine (Imuran), and leflunomide (Arava). In fact, the ACR recommends that the majority of patients with newly diagnosed RA be prescribed a DMARD within 3 months of diagnosis. Depending on which drug is selected, side effects can include myelosuppression or macular or liver damage. A main adverse effect of the DMARD MTX treatment is folate antagonism. Treatment with MTX induces a significant rise in serum homocysteine, which is corrected by folic acid supplementation and a properly balanced diet. Supplementation is advised to offset the toxicity of this drug, for protection against gastrointestinal disturbances, and for maintenance of red blood cell production without reducing the efficacy of MTX therapy. Long-term supplementation in patients on MTX is important to prevent neutropenia, mouth ulcers, nausea, and vomiting (see Appendix 31 and Chapters 9 and 31).

D-penicillamine is another DMARD, which acts as immunosuppressor by reducing the number of T cells, inhibiting macrophage function and decreasing IL-1 and RF production. Additional DMARDs include gold salt therapy and antimalarials and may lead to a remission in RA symptoms. Proteinuria may occur with administration of gold and D-penicillamine; therefore toxicity must be monitored continually. Minocycline (Minocin) is an antibiotic often used to treat mild RA (Cannon, 2009).

Surgery

Surgical treatment for RA may be considered if pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic treatment cannot adequately control the pain or maintain acceptable levels of functioning. Common surgical options include synovectomy, joint replacement, and tendon reconstruction.

Exercise

Physical and occupational therapy are often part of the initial therapy for newly diagnosed RA, but may also be integrated into the treatment plan as the disease progresses and ADLs are affected. To maintain joint function, recommendations may be given for energy conservation, along with range-of-motion and strengthening exercises. Although the patient may be reluctant at first, individuals with RA can participate in conditioning exercise programs without increasing fatigue or joint symptoms while improving joint mobility, muscle strength, aerobic fitness, and psychological well-being.

A loss of body cell mass that accompanies RA, called rheumatoid cachexia, involves the skeletal muscle, viscera, and immune system. This can lead to muscle weakness and loss of function, which may hasten morbidity and mortality in RA. Physical activity, including both aerobic exercise and strength training, seems to help. Any exercise program for an RA patient must take into account the individual’s disease status.

Medical Nutrition Therapy

The nutrition care process and model serves as a guide for implementing MNT with RA patients. See Chapter 11. A comprehensive nutrition assessment of individuals with RA is essential, with a review of systems to determine the systemic effects of the disease process. A physical examination provides diagnostic signs and symptoms of nutrient deficiencies. Current weight and history of weight change over time are the least expensive, least invasive, and most reliable assessment tools to use. Weight change is an important measure of RA severity. The characteristic progression of malnutrition in RA is attributed to excessive protein catabolism evoked by inflammatory cytokines and by disuse atrophy resulting from functional impairment (Fukuda et al., 2005).

The diet history should review the usual diet; the effect of the handicap; types of food consumed; and changes in food tolerance secondary to oral, esophageal, and intestinal disorders. The effect of the disease on food shopping and preparation, self-feeding ability, appetite, and intake also needs to be assessed. The use of elimination or other diets purported to treat or cure arthritis should be identified (Smedslund, 2010). See Chapters 4, 6, and 8.

Articular and extraarticular manifestations of RA affect the nutrition status of individuals in several ways. Articular involvement of the small and large joints may limit the ability to perform nutrition-related ADLs, including shopping for, preparing, and eating food. Involvement of the temporomandibular joint can affect the ability to chew and swallow and may necessitate changes in diet consistency. Extraarticular manifestations include increased metabolic rate secondary to the inflammatory process, SS, and changes in the gastrointestinal mucosa.

Increased metabolic rate secondary to the inflammatory process leads to increased nutrient needs, often in the face of a diminishing nutrient intake. Taste alterations secondary to xerostomia and dryness of the nasal mucosa; dysphagia secondary to pharyngeal and esophageal dryness; and anorexia secondary to medications, fatigue, and pain may reduce dietary intake. Changes in the gastrointestinal mucosa affect intake, digestion, and absorption. The effect of RA and the medications used may be evident throughout the gastrointestinal tract. Based on the patient’s unique profile, a registered dietitian can determine the most appropriate nutrition intervention, followed by monitoring and evaluation.

The association of foods with disease flares should be discussed. Whether food intake can modify the course of RA is an issue of continued scientific debate and interest. Dietary manipulation by either modifying food composition or reducing body weight may give some clinical benefit in improving RA symptoms. Some benefits may be related to a reduction in immunoreactivity to food antigens eliminated by a change in diet (Karatay et al., 2005) (see Chapter 27).

Some literature has suggested that fasting may be beneficial in reducing pain at the inflammation site; nevertheless fasting has never been shown as an effective treatment for RA symptoms (Smedslund et al., 2010). A vegan, gluten-free diet causes improvement in some patients, possibly because of the reduction of immunoreactivity to food antigens. See Chapter 27.

The anti-inflammatory diet described in Box 40-2 should be considered. The similar Mediterranean-style eating plan includes foods that almost everyone should aim to consume on a daily basis, such as moderate amounts of lean meat, unsaturated fats instead of saturated fats, plenty of fruits and vegetables, and fish. See Fig. 34-6. These diets are also nutritionally adequate and cover all of the food groups (Smedslund et al., 2010).

If food does play a role in RA, it most likely does so a few years before clinical diagnosis (Pedersen et al., 2005). Red meat has been identified as having proinflammatory properties as a source of ARA (see Box 40-1); no link has been identified between RA and coffee or tea consumption (Choi and Curhan, 2010).

Energy

Objective measures of actual energy needs for this population have not been determined. It is important to remember that the actual effect of the inflammatory response on the metabolic rate is unknown and may vary from individual to individual. In addition, activity levels vary greatly. Although traditional measures to assess energy requirements can be used, weight should be monitored and energy intake modified as needed to achieve desirable or usual body weight. Methods to determine energy requirements are noted in Chapter 2. For patients who are totally sedentary, calculations should be estimated at the resting energy expenditure and adjusted for weight changes that occur over time. When intakes are poor, enteral or parenteral supplementation may be required, and home nutrition support is beneficial for chronic cases. See Chapter 14.

Protein

Well-nourished individuals require protein at levels comparable to the DRIs for age and sex. Patients with RA tend to have increased whole-body protein breakdown (regardless of age) from growth hormone factor, glucagon, and TNF-α production. Protein may be needed at levels of 1.5 to 2 g/kg/day.

Lipids

Low-fat diets (including use of low-fat substitutes) lead to low serum levels of vitamins A and E and actually stimulate lipid peroxidation and eicosanoid production, thus aggravating RA. Therefore low-fat or fat-free dieting may actually be counterproductive for patients susceptible to or afflicted by RA. Rather than eliminating fat, changing the type of fat in the diet is useful and likely offers advantages for both the arthritis and cardiovascular systems. The anti-inflammatory diet (Box 40-2) with higher ω-3 fatty acids can reduce inflammatory activity, increase physical function, and improve vitality for RA patients.

Omega-3 fatty acids have increased in popularity in the management of RA because of their role in inflammatory pathways. Some other oils of marine origin and a range of vegetable oils (olive and evening primrose oil) have indirect antiinflammatory actions probably mediated via PG E1 (see Focus On: Fatty Acids and the Inflammatory Process). Fish oil alleviates RA symptoms and reduces the use of NSAIDS in RA patients The beneficial effects are generally delayed for up to 12 weeks after they are started but last up to 6 weeks after discontinuing therapy (Bhangle and Kolasinski, 2011). See Appendix 40 for ω-3 and ω-6 fatty acid content of foods.

Minerals, Vitamins, and Antioxidants

Several vitamins and minerals function as antioxidants and therefore affect inflammation. Vitamin E is just such a vitamin, and along with ω-3 and ω-6 fatty acids, may affect cytokine and eicosanoid production by decreasing proinflammatory cytokines and lipid mediators. Synovial fluid and plasma trace element concentrations, excluding Zn, change in inflammatory RA. Altered trace element concentrations in inflammatory RA may result from changes of the immunoregulatory cytokines (Yazar et al., 2005). Degradation of collagen and eicosanoid stimulation are associated with oxidative damage. However, there are not significant data to support routine supplementation with vitamin C, vitamin A, or β-carotene unless patients are shown to have inadequate concentrations of antioxidants.

RA patients often have nutritional intakes below the DRIs for folic acid, calcium, vitamin D, vitamin E, zinc, vitamin B, and selenium. In addition the often used drug MTX is known to decrease serum folate levels with the result of elevated homocysteine levels. Thus in these patients, adequate intakes of folate and vitamins B6 and B12 should be encouraged. Calcium and vitamin D malabsorption and bone demineralization are characteristic of advanced stages of the disease, leading to osteoporosis or fractures. Prolonged use of glucocorticoids can also lead to osteoporosis. Therefore supplementation with calcium and vitamin D should be considered. Indeed, vitamin D is a selective immunosuppressant and greater intakes of vitamin D may be beneficial. Because of drug-induced alterations in specific vitamin or mineral levels, mounting evidence supports supplementation beyond the minimum levels for vitamins D and E, folic acid and vitamins B6 and B12.

Elevated levels of copper and ceruloplasmin in serum and joint fluid are seen in RA. Plasma copper levels correlate with the degree of joint inflammation, decreasing as the inflammation is diminished. Elevated plasma levels of ceruloplasmin, the carrier protein for copper, may have a protective role because of its antioxidant activity.

Alternative Therapies

The increasing popularity of the use of alternative treatments appears to be particularly evident with people afflicted with RA. Herbal therapy is popular; however, concerns of toxicity must also be addressed because the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) provides relatively little regulation of herbal therapies.

Gamma-linolenic acid (GLA) is an ω-6 fatty acid found in the oils of black currant, borage, and evening primrose that can be converted into the antiinflammatory PG E1 or into ARA, a precursor of the inflammatory PG E2. Because of competition between ω-3 and ω-6 fatty acids for the same enzymes, the relative dietary contribution of these fats appears to affect which pathways are favored. The enzyme delta-5 desaturase converts GLA into ARA, but a diet high in ω-3 fats will pull more of this enzyme to the ω-3 pathway, allowing the body to use GLA to produce PGE1. This antiinflammatory PGE1 may relieve pain, morning stiffness, and joint tenderness with no serious side effects. Further studies are required to establish optimum dosage and duration.

Thunder god vine (Tripterygium wilfordii) has been used in China to treat patients with a number of autoimmune diseases. There are no consistent, high-quality thunder god vine preparations being manufactured in the United States. High doses and long-term use of thunder god vine may suppress the immune system and reduce bone density (NCCAM, 2009).

Sjögren’s Syndrome

Sjögren’s syndrome (SS) is a chronic autoimmune disease characterized by lymphocytic infiltration of the exocrine glands, particularly the salivary and lacrimal glands, leading to dryness of the mouth (xerostomia) and of the eyes (xerophthalmia).

Pathophysiology

Common signs include thirst, burning sensation in the oral mucosa, inflammation of the tongue (glossitis), and lips (cheilitis), cracking of the corners of the lips (cheilosis), difficulties in chewing and swallowing (dysphagia), severe dental caries, progressive dental decay, and nocturnal oral discomfort. SS can be present alone (primary SS) or as secondary SS, as a result of another rheumatic disorder (RA, lupus). Patients may also suffer from disorders of the skin, lung, kidney, nerve, connective tissue, and digestive system because of more extensive glandular damage.

SS patients frequently develop disturbances in smell perception (dysosmia) and in taste acuity (dysgeusia) (Gomez et al., 2004; Kamel et al., 2009), as well as in their dietary habits because of difficulties in biting, chewing, or swallowing.

Nutrient insufficiency may play a role in the development or progression of SS. Altered consumption of several nutrients has been noted in SS patients including higher intake of supplemental calcium and lower intake of nonsupplemental vitamin C, PUFAs, linoleic acid, and ω-3 fatty acids. Biochemical deficiency of vitamin B6 (pyridoxine) has also been observed (Tovar et al., 2002). That can be corrected by pyridoxine supplementation.

Medical Management

Medications for SS address the issues of dry eyes and dry mouth. These include artificial tears and immunosuppressant drops such as cevimeline (Evoxac) and pilocarpine (Salagen), respectively (AF, 2005b).

Medical Nutrition Therapy

The goal of dietary management in patients with SS is to relieve symptoms and reduce eating discomfort, which can result in lack of appetite, weight loss, fatigue, difficulty chewing and swallowing, mouth infections, and anemia. Management of xerostomia should also include strategies for reducing the risk of dental decay, including frequent rinsing with water, toothbrushing, using topical fluorides, or chewing sugar-free gum. Because of the lack of saliva (and the protective substances normally present in it), sugary foods should be reduced or eliminated from the diet to minimize cavities. If sugary foods or beverages are consumed, the teeth should be brushed and rinsed with water immediately.

Because swallowing is a problem, ready-to-eat foods may be useful. Foods should all be moist, and extremes in temperature should be avoided. The most common modifications include soaking or overcooking certain foods to make them softer; chopping and cutting meats and fruits to make them smaller; and limiting consumption of citrus fruits, irritant foods, and spices. The tartness of artificially sweetened, sour-flavored hard candy may help to stimulate salivary flow. Artificial saliva or products such as lemon glycerin may also be recommended by dental or dietetic professionals.

Malnutrition does not seem to be more common in this population. Iron and vitamin deficiencies such as vitamin C, vitamin B12, vitamin B6 and folate are possible, but these can be easily avoided with a well-balanced diet or appropriate vitamin supplementation.

Temporomandibular Disorders

Temporomandibular disorders (TMDs) affect the temporomandibular joint, which connects the lower jaw (mandible) to the temporal bone. TMDs can be classified as myofascial pain, internal derangement of the joint, or degenerative joint disease. One or more of these conditions may be present at the same time, causing pain or discomfort in the muscles or joint that control jaw function.

Pathophysiology

Besides experiencing a severe jaw injury, there is little scientific evidence to suggest a cause for TMD. It is generally agreed that physical or mental stress may aggravate this condition.

Medical Nutrition Therapy

The goal of dietary management is to alter food consistency to reduce pain while chewing. According to the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, diet should be mechanically soft in consistency; all foods should be cut into bite-size pieces to minimize the need to chew or open the jaw widely; and chewing gum, sticky foods, and biting hard foods such as raw vegetables, candy, and nuts should be avoided (National Institutes of Health, 2010). Nutrient intake of TMD patients appears to be the same as for the general population with regard to total calories, protein, fat, carbohydrates, vitamins, and minerals. However, during times of acute pain, intake of fiber is often reduced.

Chronic Fatigue Syndrome And Fibromyalgia

Disorders such as chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) and fibromyalgia have rheumatic symptoms. Some experts believe that CFS and fibromyalgia are variations of the same pain and fatigue syndrome. In fact, 50% to 70% of people with a diagnosis of fibromyalgia also meet the criteria for CFS and vice versa (Davis, 2005). In the US, fibromyalgia affects between 2% to 4% of the population or 12 million people (Lawrence, 2008); and CFS affects 0.007% to 2% of the general population (Avellaneda Fernández et al., 2009). Women are affected two to four times more often than men (Mayo Clinic, 2009). The etiology and pathogenic mechanisms of fibromyalgia and CFS are to date not fully understood.

CFS and fibromyalgia mimic autoimmune disorders such as SLE or hypothyroidism. Viral pathogens, immune dysregulation, central nervous system dysfunction, clinical depression, musculoskeletal disorders, and allergies have been proposed as contributing factors in CSF. In fibromyalgia, central nervous system dysfunction, mitochondrial dysfunction, nutrient deficiencies, and other systemic abnormalities have been suggested.

Mitochondrial dysfunction can result in lack of energy (ATP) for muscular work. Some symptoms include poor growth, loss of muscle coordination and muscle weakness. This can have effects on several organs and result in visual and hearing problems, learning disabilities, mental retardation, heart disease, liver disease, kidney disease, gastrointestinal disorders, respiratory disorders, neurological problems, autonomic dysfunction, and dementia (Hassani A et al., 2010).

Pathophysiology

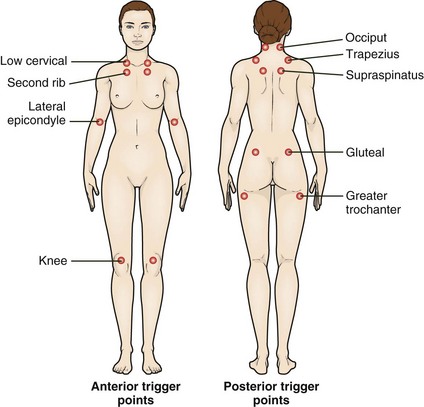

In fibromyalgia, nonarticular aches at specific pressure points (See Fig 40-5) and fatigue cause disabling symptoms including muscle tenderness, sleep disturbances, fatigue, morning stiffness, numbness and tingling, symptoms of anxiety and depression, chronic headaches, irritable bowel, and irritable bladder. In 2009, new diagnostic criteria for fibromyalgia were introduced (Wolfe et al., 2011) that do not require examination for specific tender points. Rather, diagnosis is based on the combination of chronic widespread pain and a symptom severity score based on the amount of fatigue, sleep disturbances, cognitive dysfunction, and other somatic symptoms. The diagnosis of fibromyalgia often overlaps with other chronic pain syndromes, including irritable bowel syndrome, temporo-mandibular disorders, and idiopathic low back pain (Staud, 2009). In CFS, chronic fatigue is the major symptom. It lasts 6 months or longer and is accompanied by hypotension, sore throat, multiple joint pains, headaches, postexertion lethargy, muscle pain, and impaired concentration (Avellaneda Fernández et al, 2009).

Medical Management

A treatment program for CFS should be multidisciplinary and include exercise, MNT, appropriate sleep hygiene, low-dose tricyclic antidepressants or selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), and cognitive behavior therapy (Iversen et al., 2010; Lucas, 2006).

Management of concomitant disorders, including irritable bowel syndrome, depression, and migraine headaches, can improve quality of life for these patients.

Tricyclic antidepressants and SSRIs are commonly used with CFS patients although they are not FDA approved for fibromyalgia. They may be helpful in treating depression and sleep disturbances. Side effects may include agitation, dry mouth, drowsiness, and weight gain. Analgesics such as tramadol (Ultram) may be an option for treating patients with fibromyalgia. More recently, serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) such as duloxetine (Cymbalta) and milnacipran (Savella) and the anticonvulsant pregabalin (Lyrica) have been suggested for fibromyalgia patients and are FDA approved for this purpose (Mease P, 2009, Argoff CE, 2010).

Exercise

Exercise is helpful; supervised moderate-intensity graded aerobic exercise, or water aerobics (minimum 12 weeks, 3×/week) is suggested (Busch et al., 2007; Williams DA, 2009). Similarly a multidisciplinary rehabilitation program consisting of supervised exercise therapy, group pain and stress management lectures, massage therapy sessions, and a nutrition information was found to improve self-perceived health status and pain intensity (Lemstra and Olszynski, 2005).

Medical Nutrition Therapy

Data regarding MNT for CFS are extremely limited. When hypotension is identified medically in CFS patients, increases in sodium and fluid intakes have been suggested. Evidence is not strong for elimination diets, or for the use of nutritional supplements (Häuser et al., 2008); however, vegetarian diets could have some beneficial effects probably due to the increase in antioxidant intake (Arranz LI, 2010). The vegan “living food” diet of berries, fruits, vegetables and roots, nuts, germinated seeds, and sprouts rich in carotenoids and vitamins C and E has shown anecdotal benefits. The natural antiinflammatory quercetin also shows promise (Lucas et al., 2006), as does intake of ω-3 fatty acids (Maes et al., 2005). Weight control seems to be an effective tool to improve the symptoms in these patients (Arranz LI, 2010, Ursini F, 2011). There is no specific treatment for any of the mitochondrial myopathies, physical therapy may extend the range of movement of muscles and improve dexterity. Vitamin therapies such as riboflavin, coenzyme Q, and carnitine (a specialized amino acid) may provide subjective improvement in fatigue and energy levels in some patients (Hassani A et al., 2010).

Alternative Therapies

Patients often seek complementary and alternative medicine treatments for relief. A survey of fibromyalgia patients found that 98% had used some type of CAM, including massage therapy, chiropractic therapy, and vitamin or mineral supplements (Wahner-Roedler et al., 2005). A recent systematic review with meta-analysis concluded that acupuncture may have a small analgesic effect but cannot be recommended as single therapy for management of fibromyalgia ( Langhorst J et al, 2010). Homeopathy has also proven ineffective. (Perry R, 2010). The usual treatment options appear to be limited and generally unsatisfactory. However, cognitive behavioral therapy has been shown useful in both fibromyalgia and CFS (Williams DA, 2009, Avellaneda Fernández et al., 2009).

Gout

Gout, one of the oldest diseases in recorded medical history, is a disorder of purine metabolism in which abnormally high levels of uric acid accumulate in the blood (hyperuricemia). Renal disease is common, and uric acid nephrolithiasis can occur. As the disease advances, symptoms occur more frequently and are more prolonged. Unfortunately, the prevalence of gout is increasing (Hak and Choi, 2008; Lawrence et al., 2008). In the past few decades gout has approximately doubled in prevalence in the United States, and has increased in other countries. The disease usually occurs after the age of 35 years and predominantly affects men. However, it becomes equally distributed in both sexes with age (Saag and Choi, 2006).

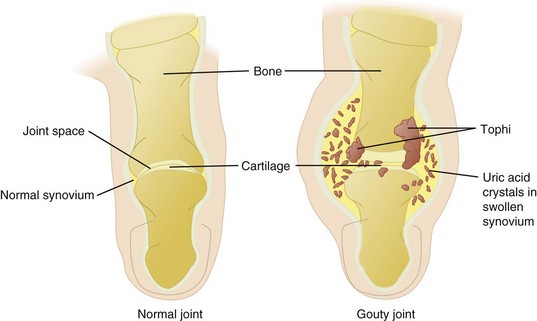

Pathophysiology

Gout is characterized by the sudden and acute onset of localized arthritic pain that usually begins in the big toe and continues up the leg. The urate deposits can destroy joint tissues, leading to chronic symptoms of arthritis (Figure 40-6). As a consequence, sodium urates are formed and deposited as tophi in the small joints and surrounding tissues. In chronic gout a classic site is the helix of the ear (Figure 40-7); a more common site is the large toe or the elbow.

FIGURE 40-6 Comparison of a gouty joint and a normal joint in the toe. (From Black JM et al: Medical surgical nursing, ed 7, Philadelphia, 2005, Saunders.)

FIGURE 40-7 Tophi on the ear of a patient who has had gout for many years. (Courtesy American College of Rheumatology, Atlanta.)

Genetic factors play an important role in the pathogenesis of gout and regulation of serum uric acid levels (Riches et al., 2009). One comorbidity of gout is obesity. Although weight loss appears to be protective (Choi et al., 2005a), ketosis associated with fasting or a low-carbohydrate diet can also precipitate an attack of gout. Occasionally the disturbance follows surgery. Hypertension and use of diuretics are also risk factors (Choi et al., 2005b). Epidemiologic studies suggest an association between gout and dyslipidemia, diabetes mellitus, and insulin resistance syndrome (Fam, 2005).

Medical Management

The goals of treatment are to reduce the pain associated with acute attacks, to prevent future attacks, and to avoid the formation of tophi and nephrolithiasis. The primary treatment for gout involves pharmacologic therapy (colchicine, allopurinol, NSAIDs, and others depending on the acute or chronic condition and renal function). Maintaining a serum urate level of less than 6 mg/dL may reduce the risk of recurrent gout attacks.

Gout is treated with drugs that inhibit uric acid synthesis. Probenecid (Benemid) and sulfinpyrazone decrease the blood uric acid level by increasing elimination through the kidneys. Allopurinol inhibits uric acid production. Both probenecid and sulfinpyrazone are often used in conjunction with colchicine, a drug that has no effect on uric acid metabolism but has been shown to relieve the joint pain of gouty arthritis. Colchicine is most valuable during the acute stage but may be needed during symptom-free periods as a preventive measure. Other antiinflammatory agents such as indomethacin or phenylbutazone are sometimes used in the acute stage of gout.

Medical Nutrition Therapy

Uric acid, derived from the metabolism of purines, constitutes a part of nucleoproteins. It appears that approximately two thirds of the daily purine load results from endogenous cell turnover, with just one third supplied by the diet (Fam, 2005). Although gout has traditionally been treated with a low-purine diet, drugs have largely replaced the need for rigid restriction of the diet. However, the patient can take an active role by adhering to the nutrition guidelines for the management of gout as well (Zhang et al., 2006).

The third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey found that higher levels of meat and seafood consumption were associated with increased serum uric acid levels in adults, but total protein intake was not (Choi et al., 2005a). It is prudent to advise patients to consume a balanced meal plan with limited intake of animal foods and alcohol, avoidance of high purine foods (see Box 40-3), limited consumption of sources of fructose (sweetened soft drinks and juices, candies and sweet pastries) (Li and Micheletti, 2011), and controlled food portion size, and reduced noncomplex carbohydrate intake to achieve weight loss and improve insulin sensitivity (Hayman and Marcason, 2009). High intake of fluids (8 to 16 cups of fluid/day, at least half as water) should be encouraged to assist with the excretion of uric acid and to minimize the possibility of renal calculi formation (Hayman and Marcasom, 2009). Dairy products (milk, or cheese), eggs, vegetable protein, cherries, and coffee (Choi and Curhan, 2010; Li and Micheletti, 2011) appear to be protective, possibly because of the alkaline ash effect of these foods. See Clinical Insight: Urine pH—How Does Diet Affect It? in Chapter 36.

Scleroderma

Scleroderma is a chronic, systemic sclerosis or hardening of the skin and visceral organs characterized by deposition of fibrous connective tissue. Women tend to be afflicted four times more often than men. Raynaud’s syndrome occurs, with ischemia or coldness in the small extremities, causing difficulty in preparation and consumption of meals. SS is often also present, but there is variability among patients.

Pathophysiology

Scleroderma is considered an autoimmune rheumatic disease with a genetic component. Free-radical, oxidative damage from cytokines, in which fibroblast proteins are modified, is involved (Kurien et al., 2006). Gastrointestinal symptoms include gastroesophageal reflux, nausea and vomiting, dysphagia, diarrhea, constipation, fecal incontinence, and small intestine bacterial overgrowth (SIBO). Joint stiffness and pain, renal dysfunction, hypertension, pulmonary fibrosis, and pulmonary arterial hypertension are also common (Scleroderma Research Foundation, 2005).

Medical Management

The disease is usually, but not always progressive, and no current treatment corrects the overproduction of collagen; therefore treatment is aimed at relieving symptoms and limiting damage. Pharmacologic therapy is often involved. Some studies have been undertaken with the use of anti-TNF therapies with some promising results (Alexis and Strober, 2005). Treatments for the pulmonary hypertension and renal crises have shown good results overall (Charles et al., 2006). The 5-year survival rate after diagnosis is 80% to 85%.

Medical Nutrition Therapy

Dysphagia requires nutrition intervention (see Appendix 35). Dry mouth with resultant tooth decay, loose teeth, and tightening facial skin can make eating difficult (Figure 40-8). Consuming adequate fluids, choosing moist foods, chewing sugarless gum, and using saliva substitutes help moisten the mouth and may offer some relief. If gastroesophageal reflux is a concern, small, frequent meals are recommended along with avoidance of late-night eating, alcohol, caffeine, and spicy or fatty foods (see Chapter 28).

FIGURE 40-8 Facial scleroderma. Taut smooth skin over the face and reduced oral aperture of a woman with long-standing disease. (From Wigley FM, Hummers LK: Clinical features of systemic sclerosis. In Hochberg MC et al., editors: Practical rheumatology, ed 3, Toronto, 2004, Mosby.)

Malabsorption of lactose, vitamins, fatty acids, and minerals can cause further nutrition problems; supplementation may be required. A high-energy, high-protein supplement or enteral feeding may prevent or correct weight loss. Home enteral or parenteral nutrition is often required when problems such as chronic diarrhea persist (see Chapter 14).

Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is commonly known as lupus. Lupus is most prevalent in women of childbearing age and is more common in blacks and women of Hispanic, Asian, and Native American descent than in whites. Common symptoms include extreme fatigue, painful or swollen joints, unexplained fever, skin rashes, mouth ulcers, and kidney problems (NIAMS, 2009).

Pathophysiology

SLE has a genetic predisposition and overproduction of type 1 interferon and other cytotoxic cells (Banchereau and Pascual, 2006). SLE is considered to be an autoimmune disease that affects all organ systems. Renal function is deranged in lupus, thus causing excessive excretion of protein and often renal failure.

Medical Management

Lupus itself and the medications used (corticosteroids, NSAIDs, immunosuppressants, antimalarials) affect nutrient metabolism, needs, and excretion. Recent therapies include rituximab, a drug also used in cancer chemotherapy which causes depletion of the immune B cells. B cell depletion helps promote remission while maintaining normal levels of IgG and IgM (Smith et al., 2006).

Plaquenil, an antimalarial drug, appears to be effective in clearing up skin lesions for some individuals with lupus but has side effects that include nausea, abdominal cramping, and diarrhea. Immunosuppressives such as cyclophosphamide may be useful when there is renal involvement, but gastrointestinal and fertility problems may occur.

Medical Nutrition Therapy

No specific dietary guidelines for managing SLE exist. Rather, the diet needs to be tailored to the individual needs of the patient. Priorities include addressing the sequelae of the disease and the pharmacologic effects on organ function and nutrient metabolism. Protein, fluid, and sodium requirements are altered as a result of disordered renal function and steroid-induced side effects. See Chapter 36. Energy needs should be tailored to the individual’s dry weight. The goal should be to attain and maintain the usual body weight. Enteral nutrition support may be required in chronic cases. Yet, because there appears to be significant crossover of symptoms among several autoimmune diseases, specific MNT guidelines prove to be a challenge.

References

Alexis, AF, Strober, BE. Off-label dermatologic uses of anti-TNF-a therapies. J Cutan Med Surg. 2005;9:296.

American College of Rheumatology. Biologic agents for rheumatic disease. Accessed 18 March 2011 from http://www.rheumatology.org/practice/clinical/position/biologics.pdf, 2006.

Anderson, JW, et al. Glucosamine effects in humans: a review of effects on glucose metabolism, side effects, safety considerations and efficacy. Food Chem Toxicol. 2005;43:187.

Argoff, CE. Fibromyalgia: Overview of Etiology, Pathophysiology, Treatment, and Management. Pain Medicine News 2010. 2010;Dec:46.

Arranz, LI, et al. Fibromyalgia and nutrition, what do we know. Rheumatol Int. 2010;30:1417.

Arthritis Foundation. Arthritis today: 2007 drug guide. Accessed 9 April 2007 from www.arthritis.org/conditions/drugguide/, 2007.

Arthritis Foundation. Arthritis today, supplements and vitamins. Accessed 20 March 2011 from http://www.arthritistoday.org/treatments/supplement-guide/facts-about-supplements.php, 2005.

Arthritis Foundation. Herbs and supplements and their uses. Accessed 20 March 2011 from http://www.arthritistoday.org/treatments/supplement-guide/index.php, 2005.

Avellaneda Fernández, A, et al. Chronic fatigue syndrome: etiology, diagnosis and treatment. BMC Psychiatry. 2009;9(Suppl 1):S1. [Oct 23].

Bahadori, B, et al. Omega-3 fatty acids infusions as adjuvant therapy in rheumatoid arthritis. J Parent Enter Nutr. 2010;34:151.

Banchereau, J, Pascual, V. Type I interferon in systemic lupus erythematosus and other autoimmune diseases. Immunity. 2006;25:383.

Beauchamp, GK, et al. Phytochemistry: ibuprofen-like activity in extra-virgin olive oil. Nature. 2005;437:7055.

Berbert, AA, et al. Supplementation of fish oil and olive oil in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Nutrition. 2005;21:2.

Bhangle, S, Kolasinski, S. Fish oil in rheumatic diseases. Rheum Dis Clin N Am. 2011;37:77.

Busch AJet al: Exercise for treating fibromyalgia syndrome, Cochrane Database Syst Rev 4:CD003786, 2007.

Calder, PC, et al. Inflammatory disease processes and interactions with nutrition. Br J Nutr. 2009;101:S1.

Cannon, M. Minocycline. Accessed 20 March 2011 from http://www.rheumatology.org/practice/clinical/patients/medications/minocycline.pdf, 2009.

Canter, PH, et al. The antioxidant vitamins A, C, E and selenium in the treatment of arthritis: a systematic review of randomized clinical trials. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2007;46(8):1223.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). National and state medical expenditures and lost earnings attributable to arthritis and other rheumatic conditions—United States, 2003. MMWR. 2007;56:4.

Charles, C, et al. Systemic sclerosis: hypothesis-driven treatment strategies. Lancet. 2006;367(9523):1683.

Choi, HK, et al. Intake of purine-rich foods, protein, and dairy products and relationship to serum levels of uric acid: the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:1.

Choi, HK, et al. Obesity, weight change, hypertension, diuretic use, and risk of gout in men: the health professionals’ follow-up study. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:7.

Choi, HK, Curhan, G. Coffee consumption and risk of incident gout in women: the Nurses’ Health Study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;92:922.

Colgazier, CL, Sutej, PG. Laboratory testing in the rheumatic diseases: a practical review. South Med J. 2005;98:2.

Davis, C. What’s in a name: fibro vs. CFS, Arthritis Foundation. Accessed 24 July 2005 from www.arthritis.org, 2005.

Egan, BA, Mentes, JC. Benefits of physical activity for knee osteoarthritis: a brief review. J Gerontol Nurs. 2010;36:9.

Fam, AG. Gout: excess calories, purines and alcohol intake and beyond: response to a urate-lowering diet. J Rheumatol. 2005;32:5.

Food and Drug Administration. FDA announces important changes and additional warnings for COX-2 selective and nonselective nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Accessed 20 March 2011 from http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/PostmarketDrugSafetyInformationforPatientsandProviders/ucm150314.htm, 2005.

Fukuda, W, et al. Malnutrition and disease progression in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Mod Rheumatol. 2005;15:2.

Galli, C, et al. Effects of fat and fatty acid intake on inflammatory and immune responses: a critical review. Ann Nutr Metab. 2009;55:123.

Gomez, FE, et al. Detection and recognition thresholds to the 4 basic tastes in Mexican patients with primary Sjögren’s syndrome. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2004;58:629.

Hak, AE, Choi, HK. Lifestyle and gout. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2008;20:179.

Hassani, A, et al. Mitochondrial myopathies: developments in treatment. Curr Opin Neurol. 2010;23:459.

Häuser, W, et al. Management of fibromyalgia syndrome—an interdisciplinary evidence-based guideline. Ger Med Sci. 2008;6:14.

Hayman, S, Marcason, W. Gout: is a purine-restricted diet still recommended? J Am Diet Assoc. 2009;109:1652.

Helmick, CG, et al. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the United States. Part I. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 2008;58:15.

Holliday, KL, et al. Lifetime body mass index, other anthropometric measures of obesity and risk of knee or hip osteoarthritis in the GOAL case-control study. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 31 October 2010. [[Epub ahead of print.] PubMed PMID: 21044695].

Huskisson, EC. Glucosamine and chondroitin for osteoarthritis. J Int Med Res. 2008;36:1161.

Huskisson, EC. Modern management of mild-to-moderate joint pain due to osteoarthritis: a holistic approach. J Int Med Res. 2010;38:1175.

Iversen, MD, et al. Self-management of rheumatic diseases: state of the art and future perspectives. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:955.

Kamel, UF, et al. Impact of primary Sjögren’s syndrome on smell and taste: effect on quality of life. Rheumatology. 2009;48:1512.

Karatay, S, et al. General or personal diet: the individualized model for diet challenges in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatol Int. 2005;26:556.

Kosuwon, W, et al. Efficacy of symptomatic control of knee osteoarthritis with 0.0125% of capsaicin versus placebo. J Med Assoc Thai. 2010;93:1188.

Kurien, BT, et al. Oxidatively modified autoantigens in autoimmune diseases. Free Radic Biol Med. 2006;41:549.

Kwon, YD, et al. Acupuncture for peripheral joint osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2006;45:1331.

Langhorst, J, et al. Efficacy of acupuncture in fibromyalgia syndrome–a systematic review with a meta-analysis of controlled clinical trials. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2010;49:778.

Lawrence, RC, et al. National Arthritis Data Workgroup. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the United States: Part II. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:26.

Lee, JH, et al. Antioxidant evaluation and oxidative stability of structured lipids from extra virgin olive oil and conjugated linoleic acid. J Agric Food Chem. 2006;54:5416.

Lemstra, M, Olszynski, WP. The effectiveness of multidisciplinary rehabilitation in the treatment of fibromyalgia: a randomized controlled trial. Clin J Pain. 2005;21:2.

Li, S, Michelleti, R. Role of diet in rheumatic diseases. Rheum Dis Clin N Am. 2011;37:119.

Lucas, HJ. Fibromyalgia—new concepts of pathogenesis and treatment. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2006;19:5.

Maes, M, et al. In chronic fatigue syndrome, the decreased levels of omega-3 poly-unsaturated fatty acids are related to lowered serum zinc and defects in T cell activation. Neuro Endocrinol Lett. 2005;26:745.

Manek, NJ, et al. What rheumatologists in the United States think of complementary and alternative medicine: results of a national survey. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2010;10:5.

Marcason, W. What is the anti-inflammatory diet? J Am Diet Assoc. 2010;110:1780.

Marcus, D. Herbal and Natural Remedies. Accessed 2005 from www.rheumatology.org, 2005.

Mayo Clinic Staff. Chronic fatigue syndrome, overview. Accessed 20 March 2011 from http://www.mayoclinic.com/health/chronic-fatigue-syndrome/DS00395, 2009.

McAlindon, TE, Biggee, BA. Nutritional factors and osteoarthritis: recent developments. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2005;17:5.

Mease, PJ. Fibromyalgia: key clinical domains, comorbidities, assessment and treatment. CNS Spectr 14. 2009;12(Suppl 16):6.

National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM). Rheumatoid arthritis and alternative medicine. Accessed 20 March 2011 from http://nccam.nih.gov/health/RA/getthefacts.htm, 2009.

National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (NIAMS). Osteoarthritis, handout on health. Osteoarthritis, handout on health, 2010. Accessed 20 March 2011 from National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (NIAMS) http://www.niams.nih.gov/Health_Info/Osteoarthritis/, 2006. [Accessed 2006 from].

National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. Systemic lupus erythematosus, handout on health. Accessed 20 March 2011 from http://www.niams.nih.gov/Health_Info/Lupus, 2009.

National Institutes of Health. TMJ disorders. NIH Publication No. 10-3487. Accessed October 2010 from www.nidcr.nih.gov/NR/rdonlyres/39C75C9B-1795-4A87-8B46-8F77DDE639CA/0/TMJ_Disorders.pdf.

National Institutes of Health. Questions and answers: NIH glucosamine/chondroitin arthritis intervention trial (GAIT). Accessed 20 March 2011 from http://nccam.nih.gov/research/results/gait/qa.htm, 2008.

Pedersen, M, et al. Diet and risk of rheumatoid arthritis in a prospective cohort. J Rheumatol. 2005;32:7.

Perry, R, et al. A systematic review of homoeopathy for the treatment of fibromyalgia. Clin Rheumatol. 2010;29:457.

Pittler, MH, et al. Static magnets for reducing pain: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. CMAJ. 2007;25(177):736.

Riches, PL, et al. Recent insights into the pathogenesis of hyperuricaemia and gout. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18:R177.

Rosenbaum, CC, et al. Antioxidants and antiinflammatory dietary supplements for osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis. Altern Ther Health Med. 2010;16:32.

Saag, KG, Choi, H. Epidemiology, risk factors, and lifestyle modifications for gout. Arthritis Res Ther. 2006;8:S2.

Scleroderma Research Foundation. Treatment information. Accessed 8 October 2005 from www.srfcure.org, 2005.

Smedslund, G, et al. Effectiveness and safety of dietary interventions for rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. J Am Diet Assoc. 2010;110:727.

Smith, KG, et al. Long-term comparison of rituximab treatment for refractory systemic lupus erythematosus and vasculitis: remission, relapse, and re-treatment. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:2970.

Snow, MH, Mikuls, TR. Rheumatoid arthritis and cardiovascular disease: the role of systemic inflammation and evolving strategies for prevention. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2005;17:3.

Staud, R. Mechanisms of fibromyalgia pain. CNS Spectr. 2009;14(12 Suppl 16):4.

Tovar, AR, et al. Biochemical deficiency of pyridoxine does not affect interleukin-2 production of lymphocytes from patients with Sjögren’s syndrome. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2002;56:1087.

Ursini, F, et al. Fibromyalgia and obesity: the hidden link. Rheumatol Int 2011. Apr 8 2011. [[Epub ahead of print]].

Wahner-Roedler, DL, et al. Use of complementary and alternative medical therapies by patients referred to a fibromyalgia treatment program at a tertiary care center. Mayo Clin Proc. 2005;80:6.

Walitt, B, et al. Coffee and tea consumption and method of coffee preparation in relation to risk of rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus in postmenopausal women. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69(Suppl 3):350.

Williams, DA. The role of non-pharmacologic approaches in the management of fibromyalgia. CNS Spectr. 2009;14(12 Suppl 16):10.

Wolfe F et al: Fibromyalgia criteria and severity scales for clinical and epidemiological studies: a modification of the ACR preliminary diagnostic criteria for fibromyalgia, J Rheum Feb 1, 2011. [e-pub ahead of print.]

Yazar, M, et al. Synovial fluid and plasma selenium, copper, zinc and iron concentrations in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2005;106:2.

Zhang, W, et al. EULAR evidence based recommendations for gout. Part II: management. Report of a task force of the EULAR Standing Committee for International Clinical Studies Including Therapeutics (ESCISIT). Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65:1312.

Zhang, W, et al. EULAR evidence based recommendations for the management of hand osteoarthritis: report of a Task Force of the EULAR Standing Committee for International Clinical Studies Including Therapeutics (ESCISIT). Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66:377.

Zhang, W, et al. OARSI recommendations for the management of hip and knee osteoarthritis, Part II: OARSI evidence-based, expert consensus guidelines. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2008;16:137.

C) of vegetables from this group is allowed daily.

C) of vegetables from this group is allowed daily.