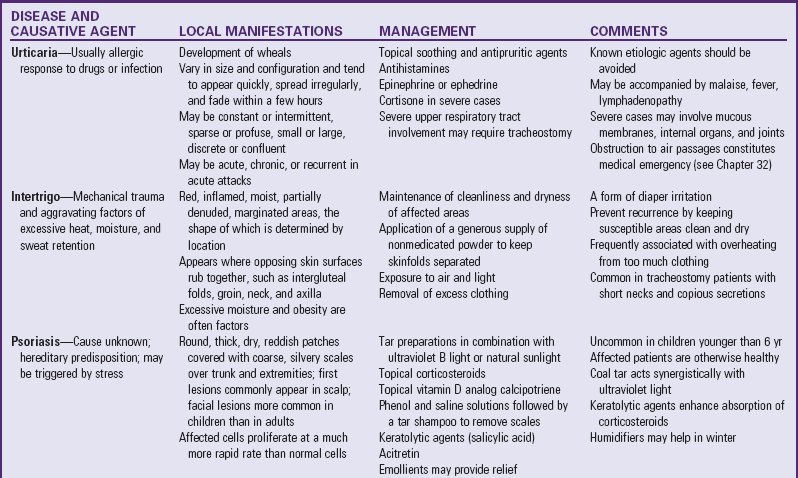

Skin Disorders Related to Drug Sensitivity

Adverse reactions to drugs are seen more often in the skin than in any other organ, although drugs can affect any organ of the body. The reaction may be a result of toxicity related to drug concentration, individual intolerance to the average dosage of the drug, or an allergic or idiosyncratic response. The manifestations may be associated with side effects or secondary effects of a drug, either of which are unrelated to its primary pharmacologic actions.

Although any drug is capable of producing almost any form of reaction in the susceptible individual, some have a tendency to produce a particular reaction consistently, and some are more likely than others to produce an untoward effect. Many such effects are allergenic responses following a prior administration of the drug, even a topical application. Other factors influence response to a drug in a particular individual. For example, the incidence of reaction increases with the amount and the number of drugs given.

Manifestations of drug reactions may be delayed or immediate. A period of 7 days is usually required for a child to develop sensitivity to a drug that has never been administered previously. With prior sensitivity the manifestations appear almost immediately. Rashes—exanthematous, urticarial, or eczematoid—are the most common manifestation of adverse drug reactions in children. However, individual drug reactions may vary from a single lesion to extensive, generalized epidermal necrosis. Cutaneous manifestations can resemble almost any skin disease and can be seen in almost any degree of severity. With few exceptions, the distribution of a drug eruption is widespread (because it results from a circulating agent); appears as an inflammatory response with itching; is sudden in onset; and may be associated with constitutional symptoms such as fever, malaise, gastrointestinal upset, anemia, and liver and kidney damage.

Another common response is a fixed eruption (i.e., a recurrent eruption at the same site with each readministration of the drug). The lesion, a purplish red round or oval plaque with a sharp border seen most frequently on the extremities, disappears slowly, and the pigmentation deepens with each episode.

In most cases treatment for simple cutaneous reactions consists of discontinuation of the drug. Sometimes a decision is made to continue the drug (such as an antibiotic in an infant or small child) until the cause of the rash is clearly indicated. In urticarial-type eruptions, antihistamines may be ordered, and for widespread and severe lesions corticosteroids are beneficial. Severe anaphylactic reactions are a medical emergency. (See Anaphylaxis, Chapter 29.)

Nursing Care Management

The most effective means of management is prevention. Parents always remember a severe response. A careful history taking will elicit evidence of a previous drug reaction. The history should include the name of the drug, nature of the reaction, drug dose, and how soon after administration the reaction occurred. (See History Taking, Chapter 6.)

Nurses who suspect that medication is the cause of the rash should withhold any further dose and report the eruption to the practitioner. Frequent offenders in drug reactions are penicillin and sulfonamides, and nurses must be alert to this possibility. However, even commonplace drugs such as aspirin and barbiturates, chemical agents in some foods, flavoring agents, and preservatives are capable of producing an undesired response. Persons who have severe reactions should wear a medical identification bracelet or necklace in case of emergency or inadvertent administration of the offending agent.

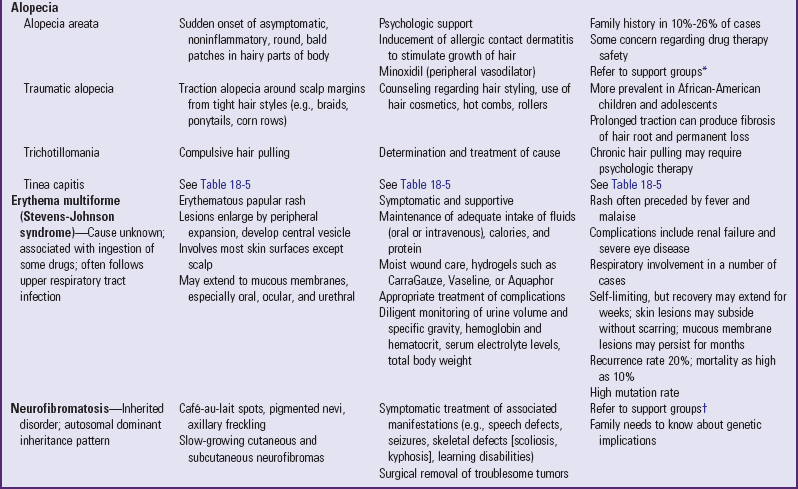

Erythema Multiforme

Erythema multiforme is an acute cutaneous disorder that may be associated with infections (usually viral) or ingestions of drugs. The characteristic lesion consists of an urticarial plaque with a dusky or vesicular center, which appears primarily on the palms, soles, and extensor surfaces.

Treatment involves discontinuing the drug, applying wet compresses for erosive lesions, and administering analgesics for discomfort. Antihistamines may be prescribed for pruritus.

Erythema Multiforme Exudativum (Stevens-Johnson Syndrome)

Stevens-Johnson syndrome is the severe form of erythema multiforme characterized by lesions of the skin and mucous membranes, fever, and multiple systemic symptoms. The disease is presumed to be a hypersensitivity reaction to certain drugs, although the reaction may follow an upper respiratory tract infection. The disorder is relatively rare, occurs at any age, and is more common in males than in females.

The syndrome begins with flulike symptoms: malaise, sore throat, fever, and severe headache. Inflammation of the glans penis (balanitis), eyes (conjunctivitis), or mouth and pharynx (stomatitis) appears next, followed in a few days by an erythematous papular rash. The lesions can involve any cutaneous surface, including the palms and soles, but usually spare the scalp. They can be scattered or confluent. The initial lesions enlarge by peripheral expansion with a vesicular center that often becomes bullous (Fig. 18-12). Mucous membrane ulceration often becomes severe enough to interfere with eating, and many patients have pulmonary involvement.

Mild disease requires only symptomatic treatment. However, severe disease necessitates hospitalization. Fluid and nutritional requirements are high, and patients often respond to topical lidocaine to relieve oral pain and a liquid diet. Intravenous opioids, such as morphine, and parenteral feedings may be needed for extensive oral involvement. Meticulous mouth care is important, and skin care frequently requires management in a burn unit. (See Stomatitis, Chapter 16, and Burns, Chapter 29.) Daily ophthalmologic examination is advised. Dry eyes are a problem, as is risk of chronic mild symblepharon (adhesion of lids to the eyeball). Eye lubricants promote moisture and comfort. Antibiotics are administered to patients with positive culture results, but the use of corticosteroids is controversial.

The mortality is estimated at 10% to 15% during the acute phase, especially in patients with pulmonary involvement. The disease is self-limiting, and the skin lesions gradually disappear without scarring in 2 to 3 weeks but may recur on reexposure to an offending drug. Wound care usually consists of cleansing with normal saline and providing a moist environment to promote wound healing. Hydrogel dressings (gauze impregnated with gel) are usually soothing and do not stick to the wound with removal (see Wound Care section, p. 691). The family needs emotional support to cope with the life-threatening nature of the disease.

Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis (Lyell Disease)

Toxic epidermal necrolysis is a drug-induced injury to the skin characterized by a generalized erythematous rash that rapidly evolves into bullae and peeling. It appears to be a hypersensitivity reaction with precipitating factors similar to those responsible for erythema multiforme. The more common offending drugs are phenobarbital, phenytoin, allopurinol, sulfonamides, and penicillin. In children the clinical appearance is the same as that seen in staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome.

The disease begins with a prodromal period of fever and malaise. Symptoms include a generalized erythematous rash that rapidly evolves into bullae and extensive epidermal peeling, and oral lesions similar to those observed in Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Treatment consists of withdrawal of the offending drug, fluid and electrolyte replacement, and skin management as for severe burns. The disease can be protracted, and mortality can range from 25% to 50%. It is essential that families of children receiving antiepileptics or sulfonamides be informed of the significance of a rash and the importance of promptly reporting it to their health professional.