Chapter 3 Over-the-counter Drugs and Complementary Therapies

Many drugs are considered safe for the treatment of minor illnesses without requiring a prescription or regular supervision of a licensed health-care professional; such drugs are available ‘over-the-counter’ (OTC). Typical OTC products are analgesics, antacids, laxatives, cough/cold preparations and antidiarrhoeal agents. Problems can occur from people self-medicating in treating minor illnesses, for example adverse effects, drug interactions, drug toxicity and drug overuse or misuse.

Complementary and alternative medicines (CAM) such as herbal therapies are also commonly employed; most of these products are not assessed for safety and effectiveness, so again problems can occur. This chapter reviews the regulatory differences between prescription-only and OTC drugs, herbal remedies and nutritional supplements, and discusses general considerations of drug marketing and consumer education for safe administration of OTC drugs, herbal remedies and various complementary and alternative therapy modalities.

Key abbreviations

CAM complementary and alternative medicine

NSAIDs non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

SUSDP Standards for the Uniform Scheduling of Drugs and Poisons

Over-the-counter drugs

Regulation of drugs

THE Australian Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA), a section of the Commonwealth Department of Health and Ageing, provides a framework for the regulation of therapeutic goods to ensure their safety, efficacy, quality, cost-effectiveness and timely availability. The National Drugs and Poisons Scheduling Committee imposes controls on drugs by setting the Standards for the Uniform Scheduling of Drugs and Poisons (SUSDP) and deciding which Schedule a drug, poison or other chemical should be placed into. The Schedules related to drugs are numbered 2, 3, 4, 8 and 9. (Schedules are discussed in further detail in Chapter 4, and outlined in Appendix 5.) The TGA also regulates many aspects of OTC products, including approved terminology, allowable colourings, levels of evidence to support claims for efficacy and safety and reporting of adverse drug reactions (ADRs).

Prescription-Only drugs

Drugs not considered safe enough for use by the general public without medical supervision are restricted to Prescription-Only status (Schedule 4 or 8 in the Australian system [see Chapter 4 and Appendix 5]). These products require the intervention of an authorised prescriber (usually a doctor, nurse practitioner or dentist) to consider the patient’s problems, diagnose pathological medical conditions, choose the most effective treatment for the patient and provide appropriate information about how to use the medicine safely and effectively. Examples might be antibiotics to treat infections or drugs for heart disease or depression. Schedule 8 includes drugs liable to cause addiction, such as narcotic analgesics and amphetamines, which require tighter controls. Once prescribed in a legally valid prescription, these drugs are available only when dispensed by a qualified pharmacist.

Self-medication

It is recognised that some conditions are sufficiently mild and/or self-limiting that people should be able to access drugs to treat themselves, for example analgesics for mild pain, decongestants for red eyes or runny noses, antimicrobials for mild infections, glyceryl trinitrate for angina, antihistamines for allergies or bronchodilators for asthma; to require a patient to visit a doctor’s surgery to renew a prescription for these conditions could be life-threatening, cause undue pain or exacerbate the condition. The stated aim of the Australian TGA in scheduling some drugs for OTC access is that ‘consumers have adequate information and understanding to enable them to select the most appropriate medications for their condition and to use them safely and effectively, taking into account their health status’ (Galbally 2000).

OTC drugs

Over-the-counter (OTC) medicines are bought and used by people to self-treat minor illnesses. Many people wish to be involved in their own health care, feel competent in undertaking self-medication and wish to avoid the time and expense involved in going to a prescriber. It has been estimated that most people visit their doctors for only 10% of their illnesses and injuries and that six out of every 10 medications purchased are OTC medications; thus OTC drugs represent a huge market. Table 3-1 gives examples of many drug groups available OTC.

Table 3-1 Examples of drugs available otc (in australia), and conditions for which they are indicated

| System or indication | Condition treated | Drug group (example) |

| Gastrointestinal tract | Peptic ulcers | H2-receptor antagonists (ranitidine); antacids (magnesium trisilicate); antimuscarinics (atropine) |

| Constipation | Laxatives (lactulose, sennosides, docusate) | |

| Diarrhoea | Antidiarrhoeals (loperamide, atropine); electrolyte replacements | |

| Haemorrhoids | Local anaesthetics (cinchocaine) | |

| Nutritional supplements | Vitamins (folic acid, vitamin C); minerals (iron, calcium); amino acids (creatine, amino acid chelates) | |

| Infant colic | Antimuscarinics (atropine, hyoscine) | |

| Cardiovascular system | Angina | Vasodilators (glyceryl trinitrate) |

| Thrombosis, myocardial infarction | Antithrombotics (aspirin) | |

| Central nervous system | Insomnia | Sedatives (diphenhydramine) |

| Nausea/vomiting | Antihistamines (promethazine); antimuscarinics (hyoscine) | |

| Nervous system | Pain | Simple analgesics (aspirin, paracetamol); plus low-dose codeine |

| Smoking withdrawal | Nicotine replacement (gums, patches, sprays) | |

| Musculoskeletal system | Pain, inflammation | NSAIDs (naproxen); salicylates (aspirin, methyl salicylate) |

| Genitourinary system | Urinary tract infections | Antiseptics (hexamine); urinary alkalinisers (sodium citrotartrate); cranberry |

| Vaginal infections | Antifungals (miconazole, nystatin) | |

| Infections and infestations | Worm infestations | Anthelmintics (mebendazole, pyrantel) |

| Head lice | Pediculicides (permethrin) | |

| Mild bacterial infections | Antiseptics (chlorhexidine, povidone iodine) | |

| Respiratory system | Coughs and colds | Decongestants (phenylephrine & pseudoephedrine); antitussives (pholcodine); antihistamines (pheniramine); various (menthol, camphor, vitamin C, bromhexine) |

| Asthma | Bronchodilators (salbutamol inhaler) | |

| Allergic disorders | Allergy, inflammation | Antihistamines (fexofenadine, loratadine); topical corticosteroids (budesonide, hydrocortisone) |

| Ear/nose/throat conditions | Swimmer’s ear | Solvents (isopropyl alcohol) |

| Nasal congestion | Decongestants (oxymetazoline) | |

| Dental caries (prophylaxis) | Fluoride (drops, toothpastes) | |

| Sore throat | Antiseptics (cetylpyridinium); local anaesthetics (benzocaine) | |

| Eyes | Infections | Antimicrobials (sulfacetamide) |

| Allergies, red eyes | Decongestants (phenylephrine) | |

| Dry eyes | Lubricants (hypromellose) | |

| Skin | Acne | Antiseptics (cetrimide, peroxides, triclosan) |

| Dandruff | Medicated shampoos (selenium sulfide, coal tar, pyrithione zinc) | |

| Warts | Keratolytics (salicylic acid) | |

| Cold sores | Topical antivirals (aciclovir) | |

| Fungal infections | Antifungals (miconazole, terbinafine) | |

| Leg ulcers | Gels (propylene glycol); dressings (calcium alginate fibres, silver) | |

| Perspiration | Antiperspirants (aluminium salts) | |

| Alopecia | Hair restorers (minoxidil) | |

| Sunburn protection | Sunscreens (PABA derivatives, zinc oxide) | |

| Insect bite prevention | Insect repellents (DEET) | |

| Surgical preparations | Pain | Anaesthetics (lignocaine nasal spray, cream) |

| Infections | Antiseptic sprays, gels, dressings, irrigations etc | |

| Diagnostic agents | Diabetes | Test kits for urinary glucose |

| Pregnancy | Pregnancy test kits; ovulation time test kits; spermicidal contraceptive gels |

DEET = N,N-diethyl-meta-toluamide; NSAIDs = non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; PABA = p-aminobenzoic acid.

Benefits of OTC availability

Factors that have led to an increase in self-medication include:

When used wisely, OTC drugs result in time and money savings, reduced workload for health professionals and, ultimately, reduced overall health-care costs. Scheduling some drugs as Pharmacy-Only (S2) or Pharmacist-Only (S3) also reduces the chance of abuse or misuse of these drugs, and leads to fewer adverse effects than might occur if these drugs were unscheduled and available without any professional oversight or counselling.

Safety and efficacy

Commonly, OTC drugs (see Table 3-1) are those considered relatively safe and effective for self-treatment by the public, assuming good manufacturing practices are followed by the manufacturer and the label directions are followed by the consumer. They are drugs with a high therapeutic index (safety margin) and/or are available in low doses or in limited supplies.

Unscheduled drugs

Drugs that are considered sufficiently safe not to require any controls, and many herbal products for which claims of therapeutic efficacy are not made, are unscheduled in the SUSDP and may be sold through many retail outlets, including supermarkets, health-food stores and general merchants, and purchased without prescription or counselling by a pharmacist, i.e. ‘over the counter’. Such drugs include most vitamins and minerals, sunscreens, medicated shampoos, and small packs of simple pain-relievers (analgesics) such as paracetamol and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) like ibuprofen. These may also be included under the umbrella of OTC drugs, depending on the definition.

Schedule 2 and 3 drugs

Schedule 2 (Pharmacy-Only) drugs are non-prescription drugs that can be bought off the shelf from a pharmacy where professional advice is available (and possibly also from some supermarkets). Schedule 3 (Pharmacist-Only) products are considered to require a pharmacist’s advice in their supply, to ensure they are used safely and effectively; indeed the pharmacist has a professional responsibility to counsel the person on safe administration of the drug. These also can be purchased without a prescription.

OTC and Prescription-Only status

Drugs in multiple schedules

A drug should not be considered to be ‘set-in-concrete’ as either OTC or Prescription-Only—a drug may fall into various drug schedules depending on the dose to be administered, the strength of formulation, number/amount in the pack, the route by which it is given or the condition for which it is indicated; and even (in Australia) the state in which it is prescribed. In certain situations, costs of drugs may be subsidised when prescribed but not when bought OTC. Examples of some drugs that ‘move around’ among Schedules 2, 3 and/or 4 are shown in Table 3-2. For example, ranitidine low-dose tablets (150 mg) for heartburn in packs of 14 are unscheduled, whereas packs of 28 are S2 and higher dose or larger packs for treatment of peptic ulcers are Prescription-Only.

Table 3-2 Examples of prescription drugs also available OTC in Australia

| Drug | OTC Schedule, dose and | Indication prescription-only schedule, dose and indication |

| Ranitidine tablets (H2-receptor antagonist) | S2: 150 mg; relief of gastro-oesophageal reflux in adults >18 years | S4: 150 mg, 300 mg tablets, injections; e.g. treatment of peptic ulcer, duodenal ulcer, Zollinger–Ellison syndrome |

| Glyceryl trinitrate (vasodilator) | S2: 0.4 mg sublingual spray; S3: 0.6 mg tablets; prevention or treatment of angina pectoris; S3: ointment for relief post-haemorrhoidectomy |

S4: 5–15 mg patches, injection; perioperative hypertension, unresponsive angina, acute myocardial infarction |

| Codeine phosphate (opioid analgesic) | S3: up to 12 mg (max 100 mg/day) and up to 5 days treatment in combination analgesics; moderate to severe pain, relief of symptoms of colds and flu, dry cough | S4: >12 mg (>100 mg/day) and/or >5 days treatment in combination analgesics; S8: codeine alone, codeine injections; moderate to severe pain |

| Nystatin oral, topical, vaginal (antifungal) | S2 or S3: 100,000 IU; oral, vaginal or cutaneous candidiasis | S4: combination ointment or ear drops with other antibiotics and corticosteroid; inflammatory and infected dermatoses |

| Salbutamol (bronchodilator/ tocolytic) | S3: 100–200 mcg/dose inhaler; asthma reliever and prophylaxis against exercise-induced asthma | S4: nebulising solution or oral syrup; asthma when inhaler administration is inappropriate; S4: obstetric injection; to delay premature labour |

| Beclomethasone (corticosteroid) | S2: nasal spray/pump 50 mcg/dose; prophylaxis and treatment of hay fever | S4: 50–100 mcg/dose inhaler; bronchial asthma |

| Hydrocortisone (corticosteroid) | S2: 0.5% cream and ointment; S3: 1% cream, spray, ointment; minor skin irritations, inflammations and itching |

S4: cream and ointment, 50 g pack, 1%; S4: injections, eye-drops, rectal foam, tablets; inflammatory conditions and as corticosteroid replacement therapy |

IU = International Units of activity.

Changes between schedules

The TGA may from time to time suggest that Prescription-Only drugs be changed to OTC status. This is based on expert findings that the drug in a particular formulation is safe and effective for use by the general public, that drug information is available and that compliance is appropriate. Certain formulations of salbutamol, hydrocortisone and ranitidine, for example, have been ‘moved down’ to S2 or S3 Schedules, as shown in Table 3-2.

On the other hand, experience sometimes shows that particular drugs do need the extra safeguards of being classified S4 (Prescription-Only), which encourages doctors and pharmacists to exercise professional judgement as to the prescribing of this drug and advising the patient. For example, all insulin formulations were moved back to Schedule 4 from Schedule 3, where they had been placed for a few years.

The range of OTC drugs

Thousands of drugs are available OTC. Many of these are discussed in detail in the systematic pharmacology chapters of this text, where their actions, mechanisms of action, clinical uses, adverse reactions and interactions and doses are described. Understanding basic information and checking package ingredients and consumer product information can help consumers make a safe and logical product selection. As an example of the Drug Monographs found throughout this book that summarise the information about clinically important drugs, in Drug Monograph 3-1 we consider the analgesic paracetamol, one of the most commonly taken OTC drugs, available in both supermarkets and general stores (unscheduled) as well as in pharmacies (Schedule 2, 3 or 4, depending on formulation and dose of other active ingredients).

Drug monograph 3-1 Paracetamol

Paracetamol, having little anti-inflammatory action, is rather different from the other non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), but is safer than aspirin as an analgesic (see Clinical Interest Box 15-9 and Figure 15-6, showing metabolic pathways of paracetamol and explaining why the drug is toxic when taken in large overdose). Its analgesic and antipyretic (anti-fever) actions are thought to be due to inhibition of prostaglandin synthesis in central nervous system (CNS) tissues via cyclo-oxygenase inhibition; a metabolite may also act via activation of cannabinoid receptors.

Indications

Paracetamol is indicated for relief of fever and of mild to moderate pain associated with head aches, muscular aches, period pain, arthritis and migraine. It is the recommended first-line treatment for osteoarthritis (Day & Graham 2005).

Pharmacokinetics

After oral administration, paracetamol is rapidly and completely absorbed from the gastrointestinal tract; peak plasma concentration of the drug is reached in 10–60 minutes. Absorption is delayed by food in the gastrointestinal tract. Distribution via the bloodstream is uniform to most body fluids and tissues, with an apparent volume of distribution of about 1–1.2 L/kg, implying some sequestration (binding) of paracetamol in tissues. There is negligible plasma protein binding. Paracetamol does cross the placenta in small amounts and so can affect the fetus. It is excreted in only small amounts in the milk of lactating women; hence it is the analgesic of choice in breast feeding mothers.

The metabolism of paracetamol occurs in the liver by hepatic microsomal enzymes. In adults the main metabolites (65%–85%) are the glucuronide and sulfate conjugates, whereas in children it is the sulfate derivative. Excretion is via the urine as metabolites (95%) within 24 hours. The elimination half-life is 1–3 hours; hence doses must be given regularly every 3–4 hours to maintain therapeutic blood levels.

Adverse drug reactions

In normal doses, paracetamol rarely causes adverse effects; dyspepsia (stomach upsets), allergy and blood reactions may occur. Because of the high therapeutic index (safety margin), accidental overdose is rare. If taken in overdose, e.g. 20 tablets instead of one or two, it is potentially fatal, with acute liver failure occurring 2–3 days later. As there may be few or only mild symptoms in the early stages after overdose (vomiting, abdominal pain, hypotension, sweating and CNS effects), any suggestion of paracetamol overdose is taken seriously. Treatment is instituted as soon as overdose is suspected, with attempts to remove the drug by gastric lavage or activated charcoal and administration of the specific antidote acetylcysteine (see CIB 15-9).

Drug interactions

There are few clinically significant drug interactions. Paracetamol may prolong bleeding times in patients previously stabilised on warfarin.

Warnings and contraindications

Caution should be used before administering paracetamol to persons with renal or hepatic dysfunction, as the drug or its metabolites may accumulate. Paracetamol is considered safe in pregnancy (Category A) and in breastfeeding.

Dosage and administration

Paracetamol is available in a multitude of formulations and dosages, and mixed with other active ingredients. The standard adult dose form is 1–2 tablets, capsules or suppositories, each containing 500 mg paracetamol, with the dose administered every 3–4 hours, not exceeding a maximum of eight per day (four for suppositories). Formulations suitable for children include infant drops, elixirs, suspensions and suppositories; dose recommendations on the basis of the child’s age or weight should not be exceeded. Small elderly patients should have doses lower than 1 g four times daily.

Common OTC drug groups

A stroll around the shelves of a large pharmacy will show the wide range and extensive number of products available OTC. (Drugs in Schedule 3: Pharmacist-Only and Schedule 4: Prescription-Only are kept behind the counter or in the dispensary.) Some of the most common groups are mentioned briefly below and are summarised in Table 3-1, with examples.

Analgesics

Pain is one of the most common and feared symptoms. For minor pain such as headache, toothache, muscle and joint aches, swelling (inflammation) and fever, many people obtain relief inexpensively with OTC analgesics. Examples are paracetamol (Drug Monograph 3-1), aspirin and other non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), some of which are available OTC. Analgesic agents are discussed in detail in Chapter 16, where morphine and aspirin are considered as the prototype analgesics.

Antacids

Various medical conditions, overeating, eating certain foods or drinking excess alcohol may result in dyspepsia (stomach upset), heartburn and indigestion. Antacids— drugs that buffer, neutralise or absorb hydrochloric acid in the stomach, and thus raise gastric pH—are commonly used for these conditions. The major ingredients in antacids are alkalis such as bicarbonate, sulfate, trisilicate and hydroxide, as aluminium, magnesium or calcium salts (see Chapter 29 and Table 29-1). Simethicone may be added to these preparations as a de-foaming or anti-gas agent.

Laxatives

Laxatives—drugs given to induce defecation—may be classified according to their site of action, degree of action or mechanism of action (see Chapter 30). Many older people are overly concerned about their bowel habits, and laxatives are often misused or abused, leading to a cycle of alternating constipation and diarrhoea.

Antidiarrhoeal agents

The term diarrhoea describes the abnormal passage of stools with increased frequency, fluidity or weight, and an increase in stool water excretion. Acute diarrhoea is usually self-limiting and resolves without sequelae. Excess fluid and electrolytes can be lost and severe morbidity and even death can occur in malnourished populations, the elderly, infants and debilitated people. Antidiarrhoeal drugs available OTC include formulations of opioids (codeine, loperamide, diphenoxylate), antimuscarinics (atropine, hyoscyamine, hyoscine), adsorbents (kaolin), demulcents (pectin), antiflatulents (simethicone) and probiotics such as bovine colostrum and Lactobacillus fermentum.

Cough/cold preparations

Every year, especially in winter, millions of dollars are spent (probably wasted) on cough, cold and influenza preparations such as antitussives, antihistamines, expectorants and decongestants (see Chapter 28). Many cough/cold products contain a combination of ingredients, some of which are in sub-therapeutic doses or are unnecessary for the particular symptoms they purport to treat. Such preparations are not considered rational and may not be safe or effective.

Antihistamines

Antihistamines are drugs that compete with histamine for its H1-receptor sites. They are commonly used to treat allergic symptoms, itching, motion sickness and as sedatives. Part of their usefulness in ‘cough and cold cures’ is due to their antimuscarinic actions, which help dry up nasal and airways secretions, and part is due to their sedative effects.

Nutritional supplements

Many people feel constrained (or convinced by advertising) to supplement their diet with extra ingredients, especially vitamins, minerals and amino acids as ‘ergogenic aids’; such supplements are available as OTC drugs or in products sold in health-food stores. Most medical authorities agree that, provided a person regularly eats a varied diet with appropriate amounts of the different food types on the food pyramid, there is no need for nutritional supplements; there is certainly little statistical evidence from clinical trials for therapeutic benefits.

There are, however, some groups in the community who may benefit from dietary supplements, particularly those with special needs, such as pregnant women or elite athletes, and those who do not have a good varied diet, such as elderly people living alone, strict vegan vegetarians, alcoholics, people on weight-loss diets or food faddists (see Clinical Interest Box 3-1).

Clinical interest box 3-1 What vitamins should i take?

A healthy 54-year-old American woman presented to the surgery requesting advice as to what vitamins she should take. She was a non-smoker, not on any special diets, who was confused by media reports that 30% of the population use vitamin supplements.

Her physician considered several approaches:

Based on a wide review of medical literature on folic acid, vitamins A, B6, B12, C, D, E and multivitamin preparations, and considering advice from some professional societies and government panels, the doctor’s advice was that ‘a daily multivitamin that does not exceed the RDA (recommended daily allowance) of its component vitamins makes sense for most adults… however, a vitamin pill is no substitute for a healthy lifestyle or diet … and cannot begin to compensate for the massive risks associated with smoking, obesity or inactivity’. Perhaps the very high prevalence of dietary supplement use by American adults (more than 70%) is based on advice such as this!

Some B vitamins and antioxidants have also been promulgated as useful in preventing dementia associated with Alzheimer’s disease; the mechanism proposed is that B vitamins lower levels of homocysteine in the body—though evidence from clinical trials for the latter suggestion is lacking.

Adapted from: Willett & Stampfer 2001; Flicker 2009; Sadovsky et al 2008.

Vitamins

Vitamins are organic compounds essential in small amounts for the body to maintain normal function and development. They were so named as a contraction of the term ‘vital amine’, as the first such essential compounds identified were amines. Many of the vitamins are considered in detail in later chapters, especially:

Vitamins are often formulated in ‘multi-vitamin’ preparations, and also in combination products particularly for children, teenagers, pregnant women or elderly people, intended to appeal to people thinking they need extra supplements.

There is a widespread fallacious view in the community that natural products (such as vitamins) are safe, whereas synthetic products have side effects (see footnote later in this chapter). However, overdoses of vitamins, especially of the fat-soluble vitamins that can accumulate in the body, can be toxic—see Clinical Interest Box 48-4 for a famous fatal case of vitamin A overdose. Similarly, taking high-dose antioxidants (vitamins A, C, E) does not prevent cancer, common colds, eye disease or old age, and can be toxic.

Minerals

Minerals are inorganic substances (not containing carbon); some are required in the diet to maintain health. Deficiency is comparatively rare, except for calcium and iron. Essential minerals are:

Clinical interest box 3-2 Selenium: a little is good, a lot is not!

Selenium is an essential trace element, chemically related to sulfur. It is not normally present in the body in detectable amounts but deficiency has been known to cause fatty infiltration of the liver and impaired thyroid function, whereas excess can cause diabetes, alopecia (hair loss) and increased risk of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis; selenium is anti-inflammatory and is teratogenic in animals (causes congenital malformations). It is used as the selenium disulfide form in antidandruff shampoos.

Although concentrations of selenium in New Zealand soils are low, there is no indication that this has resulted in any detrimental effects on the health of New Zealanders. Supplementation of animal and poultry feeds and consumption of imported plants seem to ensure that the selenium intake of most New Zealanders is at recommended levels.

Some New Zealanders take selenium supplements with the intention of reducing the oxidative damage caused by free radicals, in the hope that this will prevent cancer and cardiovascular disease, but its value in these respects has not been established.

The New Zealand National Poisons Centre receives reports from time to time that some people have consumed animal selenium supplements, well exceeding the safe daily human intake of 0.4 mg. There is no antidote for selenium overdosing, and management lies in stopping the selenium and providing symptomatic care.

Adapted from: New Zealand Prescriber Update No. 20: 39–42, July 2000 (www.medsafe.govt.nz/).

Other dietary supplements

Other dietary supplements are of a wide range and number, and are more the focus of nutrition—or Complementary and Alternative Medicine, see later this chapter—than of pharmacology. Many have been used in sport in attempts to enhance performance, e.g. pyruvate or creatine (see Clinical Interest Box 49-4); however, the fact that they are allowed by bodies such as the International Olympic Committee shows that they have never been proven to enhance performance. Others are used in attempts to enhance formation of neurotransmitters, as prophylaxis against heart disease (vitamin E, folic acid) or cancer (selenium, vitamin E) or to assist in other physiological functions deemed inadequate (coenzyme Q10 as an antioxidant; melatonin in sleep management—see Clinical Interest Box 3-3).

Clinical interest box 3-3 Melatonin, the body’s timekeeper?

Melatonin is a hormone secreted by the pineal gland. Chemically, it is an indole derivative synthesised from tryptophan via serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine, 5-HT; Figure 21-4), to which it is closely related. The metabolic activity of the pineal gland is sensitive to light and darkness, melatonin being secreted during periods of darkness and serotonin during exposure to light. Melatonin has been called ‘the endocrine messenger of darkness’ or ‘the darkness hormone’, and many wonderful claims are made for its actions and uses, most largely unsubstantiated. It is now available in Australia (but not in New Zealand) as melatonin 2 mg, S4.

By virtue of its actions in entraining the body’s circadian rhythms, melatonin can be useful in sleep management, e.g. for treating jet-lag, sleep disorders in blind people and neurologically impaired children, insomnia in the elderly and narcolepsy.

Reductions in melatonin secretion occur in many disorders, including cardiovascular diseases, Alzheimer’s disease, diabetes, migraine and in ageing, but the role of melatonin in their aetiology or pathophysiology has not been established. Secretion is reduced by alcohol, caffeine and some other common drugs.

Other roles proposed for melatonin include:

Melatonin is not without adverse effects, causing tolerance and fatigue, so it is recommended that only the lowest effective hypnotic dose should be taken, and use on consecutive nights should be avoided.

Adapted from:Kendler 1997; Zawilska et al 2009.

The terms ‘nutraceuticals’ and ‘functional foods’ have been coined to cover a wide range of (usually) natural supplements that may confer health benefits. Examples are: soy protein and phyto-oestrogens (sources of oestrogens, for menopausal symptoms and bone health), citrus flavonoids (antioxidants, anticancer and cholesterollowering), red wine and tea tannins (cardiovascular disease), dietary fibre (coronary heart disease and gastrointestinal tract regularity), probiotics, active microorganisms in yoghurt (balance gut microflora) and omega-3 fish oils (cardiac arrhythmias, insulin resistance and arthritis); see Table 3-3.

Table 3-3 Common kitchen or folk remedies

| Remedy | Potential uses or indications | Comments |

| Celery (Apium graveolens) | Anti-inflammatory; to lower serum cholesterol; chemoprotection against cancers | High in sodium; contains coumarins and flavonoids; potential interactions with warfarin |

| Cocoa (Theobroma cacao) | Many actions: antioxidant, CNS and cardiovascular stimulant, diuretic, antiplatelet; a highly nutritive food source; may protect against cardiovascular disease and premenstrual syndrome | Chocolate is made from cocoa beans dried, roasted, crushed, alkalinised, then homogenised with sugar, cocoa butter and milk; contains methylxanthines plus many other phenols, amines and minerals |

| Cranberry (various Vaccinium species) | Bacteriostatic, antioxidant | Prevention and treatment of urinary tract infections |

| Fish oils | Antiarrhythmic, lower cholesterol levels and high blood pressure, antithrombotic, anti-inflammatory, neuroprotective, chemoprotective against cancers | Contain two polyunsaturated fatty acids, also various vitamins (Bs, E) and minerals |

| Garlic (Allium sativum) | Antimicrobial, antiplatelet, coronary artery disease, lowers high blood cholesterol, hypertension, antitumour, antioxidant | Garlic contains alliin, which converted to allicin is responsible for garlic odour and potential antibacterial effects; ajoene may be responsible for its antithrombotic and antiplatelet effects, and sulfenic acid for free radical scavenging, also immunostimulant |

| Green tea (Camellia sinensis) | Antioxidant, antimicrobial, anticancer; protection against cardiovascular disease | Green tea is made from leaves that have not been oxidised; it contains flavonoid polyphenols, caffeine and other methylxanthines |

| Honey | Antibacterial, antiseptic; used in burns and to enhance wound healing | Constituents depend largely on nectar from which it is derived; may include many acids, esters, flavonoids, enzymes and beeswax |

| Horseradish (Armoracia rusticana) | Irritant to mucous membranes; circulatory and digestive stimulant | Roots contain peroxidase enzymes, volatile oils, glycosides, coumarins, acids |

| Licorice (liquorice; root of the plant Glycyrrhiza glabra) | Has mineralocorticoid and expectorant actions; extract is used as a flavouring agent and in cough mixtures | As a sweet it is compounded with sugars; main saponin is glycyrrhizin; many other ingredients, including flavonoids, sterols, coumarins, amines, sugars and oils |

| Mussels, NZ green-lipped (Perna canaliculus) | Anti-inflammatory, especially in rheumatoid and osteoarthritis | Bivalve molluscs, contain many proteins (especially pernin) and lipids; inhibits synthesis of leukotrienes hence anti-inflammatory; glycosaminoglycans enhance joint functions |

| Oats and oatmeal | Lipid-lowering actions, also antihypertensive and hypoglycaemic | Contain soluble fibre, saponins, alkaloids, starch, proteins, coumarins, flavonoids, plus minerals and vitamins |

| Soy (beans, sauce, tofu; from Glycine max) | Selective oestrogen receptor actions useful in menopausal symptoms and against cardiovascular disease, osteoporosis and some cancers | Includes isoflavones genistein and daidzein; may have phyto-oestrogenic and antioxidant activities, and improve cognitive functions |

| Yoghurt (active strains of Lactobacillus acidophilus, Bifidobacteria bifidum, etc) | After diarrhoea, or after oral administration of antibiotics, may enhance immune response, improve digestive processes; may protect against irritable/inflammatory bowel, peptic ulcers, allergic reactions | ‘Probiotics’; probably do not survive to colonise the gastrointestinal tract, but assist in re-establishing normal gut flora conditions |

Note that ‘kitchen remedies’ also include various herbs and spices (see Table 3-4).

Source: Braun & Cohen 2007, inter alia.

Use of OTC drugs

Potential problems with use of OTC drugs

Although OTC medications are generally considered to be safe and effective for consumer use, problems can arise from their use.

Self-diagnosis

Self-medication usually follows self-diagnosis of the signs and symptoms of a clinical condition. Generally, the public may consider most illnesses to be minor; however, self-treating a potentially serious condition with OTC medications may mask the condition and delay the seeking of professional help for appropriate treatment.

Adverse effects and drug interactions

OTC medicines may contain potent drugs, many of which were previously prescription-only. There has been a trend recently for the TGA to transfer more drugs to OTC status. Health-care professionals should be aware that many OTC products (new and old) are capable of producing both desired and undesirable effects, drug interactions and drug toxicity.

Labelling

The TGA regulates the appearance and content of OTC package labelling so that important information is provided in terms that are likely to be read and understood by the average consumer. Many consumers may nevertheless find that some labels are confusing and often the print is too small to read, especially by elderly people. OTC labelling that is difficult to understand and implement may result in unsafe and possibly improper use of the medication. Restrictions on labelling, packaging and storing of OTC drugs are useful but also have the potential for adding to costs and reducing competition in the marketplace.

Drug marketing

In Australia, all therapeutic goods must be registered by the TGA before they can be supplied. Therapeutic goods include anything represented to be or likely to be taken or used for a therapeutic purpose, including for disease prevention or treatment; modifying a physiological process; testing, controlling or preventing conception; or replacing or modifying body parts. (There are a few specific exclusions of well-known ingredients with a long history of safe use, such as vitamins, sunscreens and medicated soaps.) Therapeutic goods must be assessed and monitored to ensure safety, efficacy and quality. Manufacturers must be licensed and manufacturing processes must comply with the principles of ‘Good Manufacturing Practice’. Advertising is also regulated by the TGA. This compares favourably with the situation in the USA, where many goods are allowed onto the market as OTC products with little regulation, provided that they are identified as ‘Generally recognized as safe and effective’.

While such regulations are essential to protect the public, it can be argued that the scheduling of substances reduces individual freedoms by placing restrictions on who may supply or administer substances to whom and in what circumstances. This could be seen as an impediment to competition and a limit on consumer access to and choice of drugs.

Potency and efficacy

Another important concept to understand is the difference between drug potency and drug efficacy (effectiveness). Drug potency relates inversely to the amount of drug required to produce a desired effect: the more potent the drug, the lower the dose required. Potency determines dose but is rarely an important aspect to consider when selecting a drug—actions, adverse effects and pharmacokinetic aspects are more relevant clinically. When drug manufacturers claim that their product is more potent than another product, this usually means that less of the drug is necessary to produce the same effect, but does not mean that the more potent drug is also the more effective drug.

Combination products

Combination products may contain substances that are not necessary for the person’s symptoms. If the individual has an adverse reaction to the combination drug, it will be difficult to determine the ingredient responsible. Change in dosage will alter the dose of all active ingredients, which may not be appropriate. Raising the dose may cause accumulation of the drug with the longest half-life, leading to toxicity.

Consumer education for OTCs

OTC drugs are often misconceived as being very safe and thus not requiring the special precautions for taking a prescription drug safely; however, these products also have the potential for being misused or abused and inducing adverse effects. They also may be dangerous if taken in certain disease states or if taken concurrently with other drugs, food or alcohol. Health-care professionals need to be aware of these risks before administering or advising use of an OTC preparation, and need to be able to access and understand information about OTC drugs. All the potential problems with OTC drugs listed above should be considered and, if relevant, discussed with the consumer.

OTC medicines are drugs

OTC products are drugs (chemicals administered for useful effects on the body) and should be reported to any health-care provider when a drug history is being taken. A question phrased in neutral terms such as ‘Do you ever take any medicines?’ is likely to elicit a more positive and instructive response than ‘What drugs are you on?’ Instructions and warnings on the label need to be followed carefully. If the instructions seem unclear, it may be helpful to ask the pharmacist for clarification. If the symptoms for which the OTC drug is being taken are not relieved in an appropriate time as indicated on the label, a health-care provider should be consulted; many patients while self-medicating have delayed attending for professional health-care for so long that their condition has become untreatable.

‘Take as directed’

The old Latin abbreviation ‘mdu’, meaning ‘take as directed’, is now considered unhelpful. Patients attending a consultation are often anxious and inattentive when prescribers or pharmacists give advice about conditions and drugs, and later forget what directions were given. It is much more effective for the instructions to be written on the package label in specific terms such as ‘Take one tablet with a full glass of water three times a day after meals’.

All solid-dose oral medications (tablets and capsules) should be taken with a full glass of water, and the person advised to remain sitting or standing up for about 15–30 minutes afterwards, to reduce the potential for oesophageal irritation or injury. If the person has a problem with dry mouth or minor problems in swallowing, drinking a small amount of water before taking a tablet or capsule is helpful. If the drug is a sustained-release or enteric-coated form, it should be swallowed whole. If the medication is in a liquid form, a specially marked measuring spoon or glass should be used to measure each dose accurately.

Multiple dosing with similar drugs

Many products may have the same or very similar active drugs, which may differ in strength, dosage form (liquid, tablet, capsule) or in other ingredients, contributing to the problem of polypharmacy (considered in Chapter 2, see Clinical Interest Box 2-3). If the ingredients are not carefully checked, accidental overdosing is possible by taking the same or similar drugs in many different products. This is particularly a risk with NSAIDs: for example a woman may be prescribed an NSAID for an inflammatory condition, then take another NSAID for period pain and then aspirin for a headache, without realising the risk of compounding adverse drug reactions from three similar drugs.

Another aspect of different products having the same ingredients is that it may allow for product substitution. For example, dozens of antacid products are available that primarily contain only four or five recognised active ingredients. Many OTC antacids are thus virtually duplicate preparations. The generic or ‘home-brand’ product is often as effective as the ‘upmarket’ brand name product, so there is usually little, if any, advantage in consumers buying the more expensive item.

Tampering with packages

Consumers should check the selected package for tampering. There have been recent instances of commercial sabotage, in which, for example, disgruntled former employees tampered with products to insert dangerous ingredients. Most products are now contained in tamperresistant packaging, which allows the consumer to detect signs of tampering. If the package is suspect, it should be taken to the pharmacist or store manager. The expiry date should also be checked.

Sensitivity to ingredients

Consumers should read labels very carefully if they have ever had an allergic or unusual response to any medication, food or other substance, such as food dyes or preservatives, to ensure that such an ingredient is not included. Caution should be used if the individual is on a special diet, such as low-sugar, low-sodium or phenylalanine-free, because many OTC drugs contain more than just their active ingredients, and oral liquid preparations may contain high concentrations of sugar or alcohol. Women who are pregnant or breastfeeding should not take OTC medications without first consulting their health-care provider. People with underlying medical conditions, such as hypertension or diabetes, should read labels carefully to assess whether the medication may be contraindicated in their condition.

Storage

Unless instructions state otherwise, both prescription and OTC medicines should be stored in closed containers in a cool dry place, out of the reach of children; not stored in the bathroom, near windows or in damp places because heat, moisture and strong light may cause deterioration or loss of drug potency. ‘Use-by’ dates should be carefully observed.

Complementary and alternative therapies

What is complementary and alternative medicine?

The term complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) implies some treatment modality not usually taught or practised in mainstream scientific (Western) medicine. Although the terms alternative and complementary are often used interchangeably, there may be a distinction between them. Complementary indicates that some scientific validation exists, the practice is accepted and it may be integrated in mainstream health-care practice, whereas alternative generally refers to practices that are either scientifically unfounded or lacking in supporting evidence. Complementary therapies include specialised diets, exercise, osteopathy and chiropractic, counselling, biofeedback, massage therapy, relaxation, herbal therapy, acupuncture and hypnosis. Other modalities such as homeopathy, iridology, aromatherapy, macrobiotics and many others are usually classified under the alternative label. In Australia, medicinal products containing herbs, vitamins or minerals, nutritional supplements, homeopathic medicines and some aromatherapy products may all be referred to as ‘complementary medicines’.

Folk medicines

The primary pharmacological modality in complementary and alternative therapies is the administration of herbal or other natural products. Use of such products dates back to early civilisations, when it was believed that herbal extracts, minerals or folk medicines could treat or cure many illnesses (see the section ‘A brief history of pharmacology’ in Chapter 1). Table 3-3 lists some common remedies still in use today, available from the kitchen; some of these might now be termed ‘functional foods’, i.e. foods or dietary components that provide positive health benefits beyond their nutritional value, e.g. active yoghurts, enriched breakfast cereals, iodised salt and sports drinks. Other ‘kitchen’ remedies include spices such as cinnamon, cloves and ginger, and herbs such as rosemary, sage, thyme and turmeric; medicinal properties have been claimed for all these common cooking ingredients.

Use of CAM

Prevalence

In the past 20–30 years, there has been a vast increase reported in the interest in and use of alternative medical approaches in many Western countries. Recent data on usage in Australia are given in Clinical Interest Box 3-4. It is estimated that about 50% of the population use complementary and alternative therapies (not counting minerals such as calcium, fluoride or iron, or prescribed vitamins). Some of the most commonly used CAM products are glucosamine, fish oil, evening primrose oil and (in winter) echinacea; well-read people may also be aware of the use of St John’s wort as an antidepressant.

Clinical interest box 3-4 Facts and figures on cam use in Australia

Source: Xue et al 2007, inter alia.

In New Zealand, it has been shown that a substantial proportion of children hospitalised with acute medical illness had received complementary and alternative therapies before hospitalisation, as an adjunct rather than as an alternative to conventional medical care. Receiving such treatment had no effect on the severity of the illness, investigations performed, treatment administered or length of hospital stay. It is estimated that there are at least 10,000 CAM practitioners nationally, and that one in four adults visits a CAM practitioner annually. Many conventional general practitioners practise some form of CAM, mainly acupuncture, hypnosis and chiropractic.

In the UK, about 20% of people surveyed had used complementary and alternative therapies in the preceding year, with the most popular therapies being herbalism, aromatherapy, homeopathy, acupuncture/acupressure, massage and reflexology. The annual expenditure for the country was estimated at £1.6 billion for the whole nation in 1999. In other European countries, 20%–50% of residents reported using complementary and alternative therapies; herbal remedies and homeopathy are particularly popular in German-speaking countries.

Reasons for use of CAM

CAM therapies are used in a wide variety of disorders, in both prevention and treatment. This interest in CAM as part of the ‘back to nature movement’ may have been encouraged by numerous warnings issued on food additives, preservatives and synthetic products that were said to be cancer-producing substances. Other reasons given by users and practitioners of complementary and alternative therapies include:

Whatever the reason, the general public appears to be more interested than ever in taking personal responsibility for their health and wellbeing, and for trying alternative methods to self-treat their health problems. The result is a vast proliferation of alternative healers, health-food stores, natural products, organic fruits and vegetables and the use of herbal remedies. This movement has evolved into a multibillion-dollar enterprise that is not limited to specific cultural or ethnic groups.

Regulation of CAM

In Australia, over 100 years ago there were concerns about the widespread promotion and purchase of dangerous and useless medicines; a wide-ranging enquiry reported problems with secret trafficking in drugs, drug sellers not subject to licensing or examination, ingredients not being openly declared and misleading advertising.1 This enquiry may well be the forerunner of the TGA, which now regulates not only prescribed and OTC drugs but also complementary medicines including vitamins, herbal remedies, aromatherapy and homeopathic preparations, as well as traditional medicines from Ayurvedic, Chinese and other cultures, under the Therapeutic Goods Act (1989)—see www.tga.gov.au/cm/cmreg-aust.htm. The aim of regulation is to ensure the quality, safety, efficacy and timely availability of therapeutic goods. (Separate State and Territory legislation may also apply—see Chapter 4.) The TGA has the responsibility, with respect to CAM medicines, to:

The system is seen as an excellent one (see Harvey et al [2008]), and other countries have looked to it as a model. All products for which therapeutic claims are made must be assessed by the TGA for risk category. They may then be banned, exempted, Listed or Registered, depending on the ingredients and the claims made. The TGA has committees with particular responsibilities for evaluation of complementary medicines and for monitoring and implementation of complementary health care in the health system.

Listed products

Products considered of low risk, containing only permitted ingredients, are allowed to be self-assessed by the proposer, who must have documentation to back up any claims of efficacy such as ‘may help in ... condition’. Listed medicines may only carry information on indications and claims for symptomatic relief of symptoms of mild conditions, or for health maintenance or enhancement or risk reduction. For example, glucosamine (Drug Monograph 3-2) is a Listed product (Aust L 142381), and is marketed as ‘effective arthritis pain relief; slows the progression of joint damage in osteoarthritis’. The TGA evaluates the product for quality of manufacture and safety. Most complementary and alternative medicines are listed rather than registered. The Listing process is low-cost and streamlined.

Drug monograph 3-2 Glucosamine

Glucosamine is a naturally-occurring amino monosaccharide that is required in the body for formation of proteoglycans, mucopolysaccharides and hyaluronic acid, as constituents of joints, blood vessels, heart valves and mucous secretions. It is present in the chitin in shells of crustaceans, or may be produced synthetically. It is formulated as salts such as the sulfate or hydrochloride. There is controversy as to whether orally administered glucosamine actually reaches high enough levels in synovial fluid to improve chondrocyte metabolic activity; some clinical trials have shown no significant difference in responses compared to placebo. There is some evidence for the following actions: chondroprotective effect by stimulating proteoglycan biosynthesis, anti-inflammatory action, mucoprotective effect in the bowel and possibly immunosuppressive actions. Effects may take from weeks to months to be apparent.

Indications

Glucosamine is indicated for treating the pain and stiffness symptoms of osteoarthritis (OA), as well as slowing its progression; best evidence is for glucosamine sulfate in OA of the knee, and glucosamine in conjunction with chondroitin sulfate. Mucoprotective effects may be helpful in inflammatory bowel disease.

Pharmacokinetics

After oral administration, glucosamine is rapidly absorbed from the gastrointestinal tract, with peak plasma levels after about 4 hours; high first-pass metabolism limits bioavailability to 20%–25%. Unbound glucosamine is concentrated in articular cartilage and distributed to extravascular tissues. Metabolites are excreted in expired air (as carbon dioxide) and in urine and faeces. The elimination half-life has been estimated as 15–70 hours; hence doses can be given once daily.

Adverse drug reactions

Clinical trials lasting up to 3 years have shown minimal or no adverse effects. Short-term adverse effects may include mild gastrointestinal problems, drowsiness, skin reactions and headaches. It does not appear to affect glucose metabolism, or alter glucose tolerance or diabetes control.

Drug interactions

There are no clinically significant drug interactions; potentially glucosamine may enhance the antiinflammatory actions of NSAIDs or the anticoagulant effect of warfarin.

Warnings and contraindications

Caution should be used in patients with diabetes (regular blood glucose monitoring is advised) or with allergies to shellfish. Insufficient information is available to advise with respect to safety in pregnancy or in breastfeeding.

Dosage and administration

Glucosamine is usually administered orally; the standard dose is 1500 mg/day. Topical and parenteral forms are available in some countries.

Source:Braun & Cohen 2007; Huskisson 2008.

Registered products

Products considered of higher risk and those containing ingredients listed in SUSDP Schedules are subjected to rigorous assessment, regulation and monitoring by the TGA for quality, safety and efficacy. They are then classified into the various drugs and poisons schedules, which determines their availability, labelling, storage etc, or become ‘unscheduled’. For example, paracetamol (DM 3-1) is a Registered product, Aust R138820.

Other regulation

CAM professions are gradually coming under regulation and registration requirements; the state of Victoria established the first Chinese Medicine Registration Board in the Western world, and chiropractic and osteopathy are registered. In Australia many CAM providers will be registered as from July 2010. (However, some people consider that granting of registration status to less mainline professions would confer legitimacy on dubious practices.) Some universities in Australia now grant bachelor’s degrees in Chinese medicine, naturopathy, Western herbal medicine, homeopathy, chiropractic and osteopathy. The Australian Taxation Office recognises some professional CAM associations; Medicare, the universal health-care system, subsidises claims for treatment by some CAM practitioners, usually after referral by a general practitioner (GP). Almost all private health funds offer rebates for consultations by major CAM therapists. These social and regulatory forces are moving CAM closer to mainstream health care.

Types of CAM therapies

There is a very wide range of modalities, outside the scope of conventional scientific medicine, for which therapeutic claims are made. The range includes:

It can be seen that there is no clear-cut distinction between mainstream and CAM therapies; for example there is much overlap between physiotherapy, chiropractic, osteopathy and massage therapy; occupational therapy may employ dance therapy or Alexander technique; and many ‘Western’ drugs originate from herbal remedies.

Some CAM modalities are grouped under the umbrella of ‘naturopathy’, which focuses on self-healing and disease prevention through changes in lifestyle, and there are other eclectic practitioners who apply various methods in holistic therapy, e.g. mind–body medicine. To discuss all these is beyond the scope of a pharmacology textbook, so we will concentrate on the pharmacological group, particularly herbal remedies.

Herbal remedies

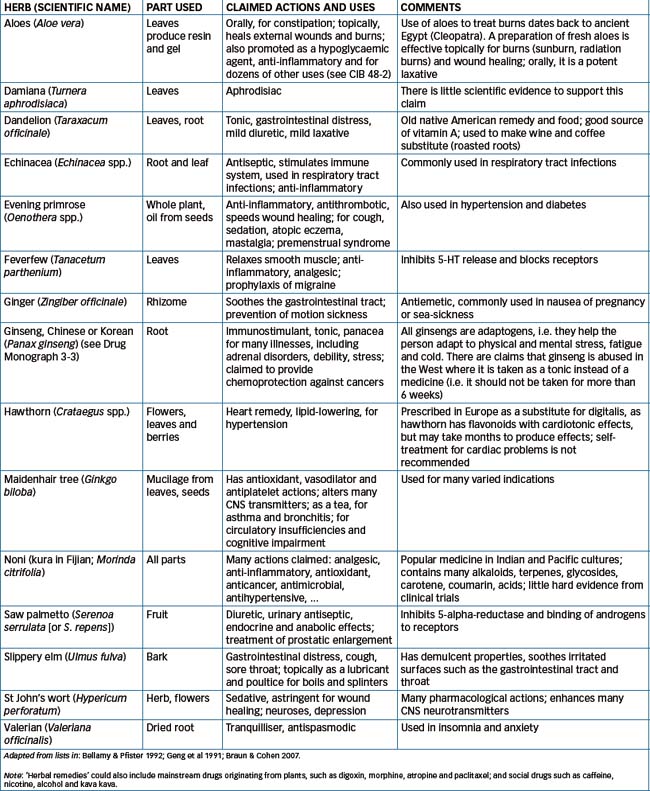

Herbal remedies, i.e. using parts or extracts of plants for treatment of illness, have been used for millennia. As described in Chapter 1 in the section on the history of medicine, ancient civilisations, including the Chinese, Egyptian, Greek and Byzantine peoples, used natural remedies and have left documentation of recipes and clinical uses. Many active medications in current use were originally discovered from plants, such as digitalis glycosides from foxglove, vinca alkaloids from periwinkle, and ephedra (ephedrine) from ma huang. Today, herbal remedies (usually partially purified extracts) are used with the main purposes of increasing the body’s natural resistance and restoring the balance of health. (Some plants from which active drugs are extracted, and the chemicals present in these drugs, are discussed in Chapter 1; the formulae of typical structures are shown in Figure 1-1.) A wide range of plants is used; a list summarising commonly used herbal remedies is given in Table 3-4.

Herbal products in Australia

The principal outlets for sale of herbal products in Australia are health-food stores, dispensaries of complementary and alternative practitioners, traditional herbal dispensaries operated by particular ethnic groups, and the Internet; pharmacies and supermarkets may also carry these products. Relevant information on ginseng is summarised in Drug Monograph 3-3, in the same format used for all other drugs, as an example of a herbal remedy; however, it will be noted that information is often unavailable for herbal products. The definitive textbook in this field is Herbs and Natural Supplements: An Evidence-Based Guide, 2nd edn (Braun & Cohen 2007).

Ginseng is a herbal product, the dried root of plants of the Panax species; Oriental (or Chinese or Korean) ginseng is from Panax ginseng. The main active constituents are saponin glycosides known as ginsenosides or panaxosides. In TCM it is considered a stimulant, diuretic and tonic for the spleen and lungs.

Pharmacodynamics

The pharmacological actions of ginseng are complex, as some ingredients have opposing actions to others; this is said to contribute to its ‘adaptogenic’ effects (helping the body respond to stresses). It inhibits the reuptake of many neurotransmitters and is said to improve physical and psychomotor performance, mental ability and wellbeing, and inhibit the development of morphine tolerance. Ginseng has gonadotrophin-like activities, including oestrogenic effects. It has anti-inflammatory actions similar to corticosteroids but has antidiabetic rather than hyperglycaemic effects. In the cardiovascular system, it has antiarrhythmic actions and may either increase or decrease cardiac performance. Low doses lower blood pressure but higher doses may raise blood pressure. The blood lipid profile is improved. It is claimed to be hepatoprotective; in some situations it is cytotoxic and in others it has antitumour activity owing to its immunostimulating actions.

Indications

The herbal preparation is used as a demulcent (soother), stomachic (to relieve dyspepsia), thymoleptic (modulator of the immune system) and, possibly, an aphrodisiac. It is indicated for nervous disorders, insomnia and depression, and menopausal symptoms. In TCM, it is indicated for leucopenia, shock, diabetes and mental fatigue.

Pharmacokinetics

Ginseng extracts have a sweet, slightly bitter taste. When taken orally, ginsenosides are mostly metabolised by intestinal bacteria to the monoglucoside, which is detected in plasma from 7 hours after the intake of ginsenosides and in urine from 12 hours after the intake. (Little further pharmacokinetic information is available.)

Adverse reactions

Ginseng is considered to have low toxicity but adverse effects are difficult to assess objectively because of differences between preparations as to the type of ginseng, dose and purity of preparations. Adverse reactions noted include insomnia, hypertension, diarrhoea, mastalgia, vaginal bleeding and skin eruptions. In TCM, it is noted that ‘allergies’ can lead to palpitations, insomnia and pruritus (itching).

Drug interactions

Ginseng has the potential to interact with a wide range of drugs, either enhancing or inhibiting their actions, especially warfarin, digoxin and all drugs metabolised by CYP1A. All of these potential interactions emphasise the importance of people who are using ginseng discussing this with health-care professionals, especially those considering prescribing other drugs.

Warnings and contraindications

Guidelines suggest that ginseng is contraindicated in acute illness and haemorrhage, and should be avoided by people with nervousness or schizophrenia, by healthy people aged under 40 years and by pregnant or lactating women. Long-term use should be avoided. Ginseng should be used with caution by patients with cardiovascular disease or hypertension.

Herbal products in the United Kingdom

The British have a long history of interest in and clinical use of herbal remedies. There is an official British Herbal Pharmacopoeia 1996, produced by the British Herbal Medicine Association. This gives detailed monographs for about 170 standard herbal remedies, with information on their characteristics, identification, quantitative standards and claimed actions. Appendices give methods of analysis to determine the strength and purity of the preparations.

Other pharmacological CAM

Non-herbal supplements

Essential oils and aromatherapy

Other pharmacological natural products include essential oils and the extracts used in aromatherapy, Bach flower products and scented candles, in which the volatile oils, esters, alcohols and many other chemicals from the plants may contribute to the aromas and their effects on the senses and body functions. Aromatherapy with wildflower essences is used in some hospitals for stress and pain management. Tea-tree oil has become one of the most commonly used natural remedies in Australia, and its popularity has spread internationally. The essential oil from Melaleuca alternifolia (see Figure 3-1B), tea-tree oil contains many active constituents, including terpenes such as cineole. Its main proven actions are antifungal, antibacterial and antiviral (against herpes simplex); it is used particularly in skin infections and in podiatry, and as a cosmetic.

Homeopathy

Homeopathy is a form of treatment in which substances (minerals, plant extracts, chemicals or microorganisms) that in sufficient amounts would produce a set of symptoms in healthy persons, are given in minute amounts to produce a ‘cure’ of similar symptoms. It is based on the teachings of a German physician–pharmacist Samuel Hahnemann (1755–1843). Homeopathic ‘remedies’ based on extracts of plant drugs, such as atropine, quinine and arnica, and copper, zinc, calcium and mercury are used.

The homeopath is said to encourage the body’s own healing by stimulating a ‘vital force’ by administration of an extract of fresh natural product, a process known as ‘proving’ the drug. The mother tincture is then diluted thousands of times,2 with vigorous shaking and tapping (succussion), which is said to release the power to heal. Each serial dilution is said to increase the ‘power’ of the medicine. Care must be taken not to contaminate the preparation with anything that could affect its ‘potency’. Formulations include tablets, drops, tinctures and powders.

The lack of scientific rationale for homeopathic principles, in particular the total negation of accepted dose–response relationships, and lack of scientifically acceptable and repeatable evidence for clinical efficacy in randomised controlled double-blind trials, make this modality anathema to pharmacologists trained in pharmacodynamic principles. It is nonetheless widely practised in Europe and followed by many influential people, including royalty. (In 2010 the UK government announced its intention to stop subsidies for homeopathic treatments, due to lack of any evidence of efficacy.) In Australia, homeopathic preparations are exempt from regulation by the TGA unless they contain ingredients of human or animal origin, but labels must state that they are not approved by the TGA, and cannot claim to cure serious illnesses.

A recent meta-analysis (Ernst 2010) systematically reviewed all relevant papers for and against homeopathy, using the Cochrane Database as the source of reviews. The author, himself the Director of Complementary Medicine at the Medical School of the University of Exeter, UK, concluded that ‘the most reliable evidence… fails to demonstrate that homeopathic medicines have effects beyond placebo’.

Traditional medicine practices

Australian Indigenous medicine

The traditional Australian Aboriginal beliefs about causation of illness emphasise social and spiritual dysfunction as the main causes, with supernatural intervention causing serious illness. Some quite sophisticated ‘bush medicine’ methods have been developed (see Clinical Interest Box 3-5). The medicinal properties of many Australian native plants may have been used by Indigenous people for over 60,000 years. The diversity of plant species throughout Australia enabled the many distinct Aboriginal tribes and clans to develop a great range of traditional remedies, which were administered by various routes. Plants commonly used included Eucalyptus (gum tree) and Melaleuca (tea-tree) species for coughs and colds, Barringtonia as a fish poison, Leichhardtia as an oral contraceptive and Euphorbia topically for skin lesions (see Figure 3-1).

Clinical interest box 3-5 Indigenous australian plant remedies

The origins of Australian Aboriginal ethnobotany and traditional medicinal plant usage predate Western medicine by many millennia, and are still preserved and implemented today. Active constituents of plants are known to vary in strength, both seasonally and geographically. Traditionally, plants were used as fresh preparations in a range of ways:

Such products are used as antiseptics, analgesics, astringents, sedatives, hypnotics, expectorants and carminatives. Effective antibacterial activity has been proven for extracts of leaves from many Australian plants used in traditional Indigenous ways, including:

Adapted from: Collins et al 1990; Cribb & Cribb 1988; Lassak & McCarthy 2001; Low 1990; Zola & Gott 1992; Pearn 2005.

The knowledge of preparation and use of medicinal plants has largely been inherited through oral tradition. Traditional tribal healers are identified early and given special training by older healers, often the grandmothers in the tribe. Unfortunately, as these practices become more infrequent and the number of tribal elders with such knowledge diminishes, there is concern that much of this invaluable information may be lost, so it is important that the information be documented. There are many scientific journals, reference books, interest group newsletters and government reports in which the identification of useful species, their active ingredients and medicinal uses are noted. This information is fragmentary, however, often focusing on only one species or one region; for example, the central and northern Australian remedies have been more widely documented than those of eastern states.

Comparatively few native plants have been tested for their chemical or pharmacological properties. It is promising to note, however, that studies on the active ingredients of indigenous plants are being conducted in both Australian and overseas laboratories. Aromatic leaves, tannin-rich inner barks and ‘kinos’ (resins and gums) of several species have well-documented therapeutic effects. Other plants undoubtedly contain alkaloids or other compounds with pronounced clinical effects. As yet, no comprehensive database has been constructed to make this information easily accessible to the general public, although a chemical and pharmacological survey of Australian plants was carried out by the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) some years ago (Collins et al 1990). A web-based database has been set up to assist integrating knowledge on Australian Aboriginal medicinal plants (see Gaikwad et al [2008]); and an ethnopharmacological study of medicinal plants in NSW is working to preserve and research best practices to protect traditional knowledge (Brouwer et al 2005).

Traditional Eastern compared with Western medicine

With the major influxes into Australian society of immigrants from Asian countries, including Vietnam, Korea, Hong Kong, China and Indonesia, there has been increased interest in and usage of Eastern medical practices. There is a major difference between the Eastern (Asian) and Western philosophical approaches to health care: in Eastern or Asian medicine, the emphasis is on health promotion or stabilisation, as opposed to Western concepts of illness intervention and treatment of symptoms (although the concepts of ‘holistic medicine’, i.e. considering the whole person, and of public health measures and prevention are becoming more important). For example, bronchitis symptoms may include excessive mucus secretion in the bronchi, cough, frequent chest infections and cyanosis. Treatment may include a systemic antibiotic for the infection, an expectorant and postural drainage for the mucus, and advising the patient not to smoke. If necessary, a bronchodilator and oxygen may be ordered. Eastern treatment might use some of these therapies but would also include approaches to help the individual regain ‘energy balance’ to reduce further episodes. Depending on the practitioner, the approaches can vary considerably. Meta-analyses of some TCM remedies are beginning to appear in medical literature, to attempt to bring TCM into the era of evidence-based medicine (see Li and Brown [2009]).

Traditional Chinese medicine

In traditional Chinese medicine (TCM), maintaining an energy balance in the body is considered most important; a balance between yin (negative) and yang (positive) forces is necessary to maintain good health. The Chinese physician may thus prescribe a variety of interventions such as herbal therapy, acupuncture, moxibustion, diet changes, exercise, meditation or the services of a spiritual healer. Herbal remedies have been studied for thousands of years, so this knowledge is used with other therapies to achieve a balance within the body to help regain and maintain good health.

In Chinese herbal medicine, herbs are either taken orally or applied externally to correct the physical disorder. Herbs are described by their properties, e.g. heat-clearing herbs, Qi-regulating herbs or Yin-tonifying herbs. Texts such as the Chinese Materia Medica (Zhu 1998) describe the philosophy and techniques of TCM materia medica (pharmacology), with guidelines for the harvesting, production and application of the materials. Monographs on products may describe the chemistry, pharmacology, adverse effects and toxicity, the traditional description, indications for use and applications of the remedy, and the dose and how it is administered.

In TCM it is believed that herbal preparations are much more effective when used in a balanced formula (see case history in Clinical Interest Box 3-6), and that ingredients have synergistic effects, i.e. actions are magnified when taken as mixtures (however, there is little scientific evidence for this). Ginseng (Drug Monograph 3-3), for example, may energise the body (especially the lungs, spleen and pancreas) but it can also cause strong adverse effects if used alone. The ginsenosides in ginseng can constrict arteries but if ginseng is combined with other herbs such as kudzu or astragalus, the adverse effects are believed to be balanced. Another example is the combination of bitter orange, ginseng and ginger; the bitter orange is the key herbal that stimulates the body’s vital energy (Qi), ginseng energises the body by providing a warmer energy and ginger is included as an assisting herbal (i.e. it helps to relax muscle tissue). This combination is chosen for the individual effects plus the effects in combination. This combination may be used to treat muscle aches (muscle relaxant) and digestive tract problems, and in people who need to strengthen their Qi energy.

Clinical interest box 3-6 A TCM herbal remedy case history

A woman patient was brought into the medical ward with possible atypical pneumonia, plus post-viral fatigue after severe glandular fever and Epstein–Barr virus infections. Recently she had been taking herbal tablets prescribed by the local TCM practitioner, 30 (repeat, thirty) tablets per day. Each tablet allegedly contained:

The concerned emergency department doctors did a quick search through reference sources to determine whether any of the ingredients might be potentially either effective or toxic in this situation. In summary:

It was quickly realised that while some of the herbs were possibly useful in respiratory infections, the ‘doses’ in the tablets were far too low to be effective, even if 30 tablets were taken daily. On the other hand, Fritillaria thunbergii is potentially poisonous.

The patient was advised to cease taking the herbal tablets and, after ceasing and treatment with appropriate antibiotics, made a full recovery.

Source: Personal communication from Dr Philippa Shilson, Geelong, 2009.

African traditional medicine

Traditional medicine practitioners in many African countries include herbalists, midwives, bone setters, faith healers and spiritualists. Disease is considered to arise not only from physical and psychological causes but also from astral, spiritual and other esoteric causes. African traditional medicine provides holistic treatment, and may include herbal, mineral and animal remedies, administered orally as liquids, topically as powders, ointments or balsams, or by inhalation. Parenteral routes are rarely used. Other types of African traditional medicine include diets and fasting, hydrotherapy or dry heat therapy, surgical operations, bloodletting, spinal manipulation, faith healing and occultism.

Several important drugs have come into Western medicine from traditional African remedies, including physostigmine (an anticholinesterase), yohimbine (an α-receptor antagonist resembling the ergot alkaloids), reserpine (an alkaloid from Rauwolfia and a former antihypertensive and neuroleptic agent that caused severe depression) and ouabain (from Strophanthus species, a cardiac glycoside).

Currently, in South Africa it is estimated that there are over 350,000 traditional healers, offering medicinal plants to 60%–80% of the population. Plants are used as herbal extracts and also as muthi, plant material processed to be used to achieve healing, cleansing and protection from evil spirits or witchcraft. Biomedically valuable indigenous plants, including Pelargonium species, Harpagophytum and ‘devil’s claw’, are being assessed for pharmacological activity, as part of nation-rebuilding in the ‘African Renaissance’; however, there are concerns about the ethics of ‘bio-prospecting’ to exploit traditional knowledge for profit (see Reihling [2008]).

Ayurvedic medicine

Ayurveda, the indigenous healing system of India, has been practised there for more than 5000 years, focussing on prevention and self-care to restore health balance. It has been called ‘the science of long life’, as it takes a holistic approach to health and lifestyle management, incorporating exercise, diet, life activities, psychotherapeutic methods, massage and botanical medicine. Common spices are utilised, as well as herbs, herbal mixtures and preparations known as Rasayanas. Research and clinical trials are being carried out on the use of Ayurvedic medicine in treatment of anxiety, depression, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, tuberculosis and Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s diseases.

Traditional Indian spices are utilised in Ayurvedic medicine, and good results have been achieved with turmeric in wound healing, rheumatic disorders, rhinitis, gastrointestinal disorders and worm infestations; with curcumin in decreasing DNA damage and reducing mutations and tumour formation; and fenugreek seeds in reducing blood glucose and lipid levels. Garlic, onions and ginger have all been shown to impair the process of carcinogenesis.

Traditional medicine in the Pacific region

In the southwest Pacific region—from Palau and the Federated States of Micronesia in the west, through East Timor, the Solomon Islands, Vanuata, Tuvalu, Fiji, Samoa, Tonga, to the Cook Islands and Kiribati in the east—waves of settlements with Pacific peoples and then colonists from Europe brought with them plants that became adapted to coastal areas, grasslands, tropical rainforests and gardens. Many plants were found to be useful for medicinal purposes, and all the immigrant groups brought with them traditional remedies, leading to a rich mixture of medicine practices.

In Fiji, diseases were traditionally considered to be mate vayano—illnesses of the body, resulting from accidental circumstances, e.g. coughs, colds, headache and injuries, or mate ni vanua—diseases of the land, caused by spirits, magic, behaviour or sorcerers. The dauvakatevoro (people who could control evil spirits) might use herbs, secretions of the victim or yagona (kava preparations); potions from plants were believed to have magical powers to change emotions or morals. For example, leaves of kalabuci damu were chewed to ensure safety on unfamiliar tracks; those who dug graves must eat a kura leaf afterwards; and moli karokaro (lemon trees) were grown near houses for fruit and for protection. Prior to white settlement, there were few acute diseases in Pacific island countries, but European contact brought new epidemics: measles, ’flu, whooping cough, chickenpox, smallpox, cholera and venereal diseases, which devastated the vulnerable populations. As living standards have changed towards Western lifestyles, it is now the non-communicable diseases that are the major public health problems, such as obesity, diabetes and cardiovascular disease.